Adapted from the University of Michigan’s Counseling and Psychological Services Faculty Toolkit, which was made possible through a generous donation from the Baldwin Foundation

download a PDF version of the faculty toolkit

How Are You - Really?

Over the past year, a multidisciplinary committee from Health & Wellness and PACS have collaborated to develop the How Are You – really? campaign. The intent of this campaign is to expand the UNH community’s understanding of mental health and well-being and to empower students to take an active role in taking care of themselves and utilizing resources as needed. In this campaign, we conducted a number of listening groups with UNH students, faculty, and staff to help shape the development of resources to use to support student well-being.

A notable theme that emerged from these groups was the influence that faculty (and academics overall) can have on student well-being, and how unsupported and overwhelmed faculty often feel in trying to respond to the seemingly ever-increasing mental health needs of students. Thus, our committee determined that a resource guide for faculty would be of value, and in our research on such guides, we found the University of Michigan faculty toolkit entitled, Fostering a Campus Environment Supportive of Student Mental Health. We are sincerely thankful for the University of Michigan’s generosity in allowing us to adapt this toolkit for the UNH community. For further detail on the University of Michigan’s process in developing this toolkit and their specific acknowledgements, please refer to the University of Michigan Toolkit Development Process and Acknowledgements section below.

How Do I Use This Toolkit?

Thank you for what you do every day to support UNH students, and thank you for considering the resources and suggestions contained in this toolkit. We hope this resource will serve as a valuable guide in the following ways:

1. Helping you create a classroom environment that is supportive of student mental health.

2. Providing you with tips on how to identify and help a student who may be struggling with their mental health.

The strategies included in this guide are based on research, as well as ideas, techniques, and tips that faculty and students have found to be effective in supporting student mental health and well-being. However, not all strategies will be the “right fit” for everyone. Think of this resource as you would a toolkit—it provides a variety of strategies and ideas from which to pick and choose. When considering the tools you would like to try, consider your professional role, how you typically interact with students and other factors that might influence what is most useful for you.

A Continuum of Mental Health

A major part of the How Are You – really? campaign involved developing the Mental Health Continuum to remind students to check in with how they are really doing, and to find appropriate resources to support their needs throughout campus. We envisioned students not only using this tool for and amongst themselves, but faculty and staff using it to help guide their conversations with students who may need additional support as well.

With this campaign, we hope to normalize the understanding that well-being fluctuates, encourage our community to regularly check in with themselves and each other, and seek out appropriate resources based on their current needs and situation. There are many resources throughout campus that support student emotional well-being beyond PACS and H&W, and many of these offices and programs are highlighted on the continuum below and throughout the rest of this Toolkit.

What is Psychological and Counseling Services (PACS)?

Psychological and Counseling Services (PACS) provides confidential psychological services for UNH graduate students and undergraduate students currently enrolled in five or more credits in the following colleges:

- College of Engineering & Physical Science

- College of Health & Human Services

- College of Liberal Arts

- College of Life Sciences and Agriculture

- Graduate School

- Peter T. Paul College of Business and Economics

Our office is staffed by clinical psychologists, clinical social workers, mental health counselors, doctoral-level interns, and postdoctoral fellows. We strive to provide the following services in an atmosphere that is welcoming, comfortable, and multi-culturally sensitive for all students:

- Individual Counseling

- Group Counseling

- Psychoeducational Workshops

- Consultations for faculty, staff, and parents

- Urgent/Crisis Services

- Case Management and Referrals

- Community Engagement & Outreach

Urgent/Crisis Walk-In Services: Same day urgent appointments are available for students who are in crisis or have a need to be seen immediately. These can be scheduled by calling our front desk or walking in to PACS

PACS After Hours: For assistance with urgent mental health concerns and to speak with a licensed mental health professional when PACS is closed, call 603-862-2090 and dial “0”.

|

Where is PACS located? |

Smith Hall, 3rd Floor, Room 306 |

| What are the hours of operation? |

Fall/Winter Hours: Monday-Friday 8a-5p Summer Hours: Monday-Friday 9a-4p |

| Phone: (603) 862-2090 | Website: www.unh.edu/pacs |

For more Information About PACS or to Schedule an Appointment Online

What is Health and Wellness?

UNH Health & Wellness is an integrated health and wellness service that operates from a holistic perspective. Our staff consists of physicians, nurse practitioners, nurses, medical assistants, a psychiatrist, radiology staff, and Living Well educator/counselors. We provide medical care, ancillary services, wellness education, health promotion, and integrative mindbody services. We work closely with our colleagues in PACS to coordinate mental health care and services.

- Medical Services: Routine illness and injury care; allergy services; chronic illness support; mental health/psychiatric care; gender affirming care; immunizations and travel clinic; sexual and reproductive health; and laboratory, radiology prescription and non-prescription medication services.

Living Well Services: Our Living Well Services department is committed to helping students make lasting behavior changes that support their academic and personal growth.

- Our education/counseling services, prevention initiatives, and internship opportunities empower students to gain knowledge, enhance self-awareness, and implement life-long skills and behaviors to be happy and well.

- We work from a whole-person and well-being framework with expertise is in the following areas:

- Alcohol, nicotine, cannabis and Other drugs

- Eating concerns and body image

- Emotional wellness (stress, mental health)

- Nutrition

- Sexual well-being

- Well-being and wellness (sleep, stress, mindfulness and medication, financial literacy)

- Integrative mind-body services: These services can increase your ability to cope with stress, manage pain, and reinforce your overall well-being. They include biofeedback, light therapy, and mindfulness meditation workshops.

Health & Wellness After Hours: Students with a medical need can call (603) 862-9355 and follow the instructions for after-hours care. They will be automatically connected with a medical call center, where staff will conduct a phone assessment and make suggestions for additional care options, including a visit to an urgent care center or hospital, if appropriate.

| What are the hours of operation? |

Monday-Thursday 8a-4:30p Friday 9a-4:30p |

| How do I contact Health and Wellness? |

Phone: (603) 962-9355 (WELL) Website: www.unh.edu/health Social Media: @UNHealth |

For more Information About Health and Wellness or to Schedule an Appointment Online

Providing a Supportive Environment for Students

Creating a Supportive Environment

Creating an academic environment supportive of student mental health may include open and regular conversations about mental health, reframing what success looks like, and being intentional about course design. Incorporating these practices into your teaching can help alleviate stress for students and can be particularly helpful for students experiencing mental health concerns. The instructional practices used in the classroom will vary based on several factors, including, but not limited to, the material and subject matter taught and the size of the classroom (i.e., discussion section or large lecture).

- Include information about student mental health resources in your syllabus. Consider adding the recommended syllabus statement from Faculty Senate and discussing it on the first day of class.

- Student Mental Health and Well-Being: Your academic success and overall mental health are very important. If, during the semester, you find you are exexperiencing emotional or mental health issues, please contact the University’s (PACS) (3rd floor, Smith Hall; 603-862-2090/TTY: 7-1-1) which provides counseling appointments and other mental health services. If urgent, students may call PACS M-F, 8 a.m.-5 p.m., and schedule an Urgent Same-Day Appointment.

For more information about PACS

- Student Mental Health and Well-Being: Your academic success and overall mental health are very important. If, during the semester, you find you are exexperiencing emotional or mental health issues, please contact the University’s (PACS) (3rd floor, Smith Hall; 603-862-2090/TTY: 7-1-1) which provides counseling appointments and other mental health services. If urgent, students may call PACS M-F, 8 a.m.-5 p.m., and schedule an Urgent Same-Day Appointment.

According to recent student focus groups, the following practices have been found to be helpful to further support student mental health and well-being:

- Acknowledge mental health openly throughout the semester to destigmatize it, e.g., “We are approaching midterms, which can be a stressful time. Please make sure you take care of yourself and know that we have an array of mental health services available on campus.”

- Check in during stressful times, such as midterms and finals, or during national, global, or campus events that may increase students’ stress.

- Design a flexible syllabus, e.g., allowing a certain number of absences without an impact on participation grades, granting extensions, or providing the opportunity to drop the lowest exam grade or make corrections. Allowing for mistakes and flexibility can keep students motivated even if they fall behind or miss class due to health or personal issues.

- Acknowledge and celebrate multiple forms of learning by incorporating smaller discussion groups or partner sharing, including a variety of content to accommodate visual and auditory learners, allowing participation points geared toward both introverted and extroverted students, and assigning coursework that incorporates a variety of different learning styles.

- Create community guidelines during the first class session, deciding as a class what an inclusive classroom means to them and establishing norms for respectful dialogue, especially around challenging subjects.

- Prioritize accessibility for all students, e.g., putting captions on videos shown in class, image descriptions on presentations, setting up the classroom in an accessible way, etc.

- Close each class with something positive, for example have students share something they learned or something they are interested in learning more about in the next class.

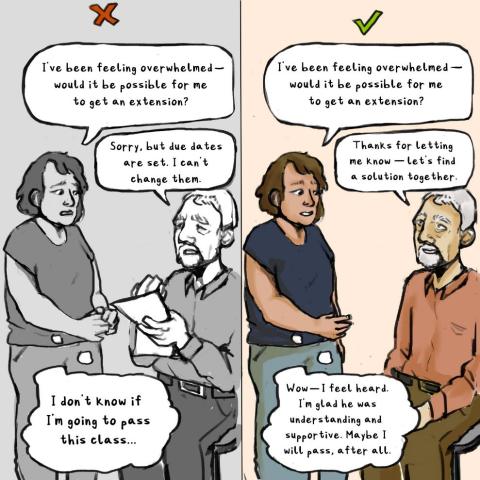

Examples of Supportive Conversations

“My professor made a point of identifying and contacting students who were struggling in their large class to see if they could help.”

“It is helpful when a stressful event happens on campus and the professor or TA acknowledges it and opens up as a safe space for students to voice their concerns.”

poor example:

STUDENT: "I've been feeling overwhelmed. Would it be possible for me to get an extension?"

FACULTY: "Sorry, but due dates are set. I can't change them."

good example:

STUDENT: "I've been feeling overwhelmed. Would it be possible for me to get an extension?"

FACULTY: "Thanks for letting me know. Let's find a solution together."

Fostering Social Support

Social support can have a direct impact on student health and well-being, with students with higher quality social support being less likely to experience mental health concerns (Hefner & Eisenberg, 2009).

Social connectedness can also affect college student retention (Allen, Robbins, Casillas, & Oh, 2008), and has been shown to be positively correlated with achievement motivation (Walton, Cohen, Cwir, & Spencer, 2012). You can help your students’ mental health and well-being, as well as their academic performance, by helping to foster connection, encourage inclusivity, and build community.

- Send an email or survey to students before the first day of class to get to know them. Ask about their backgrounds, interests, strengths, needs, and other topics, and try to adjust the classroom and course content accordingly.

- Learn the names of students and encourage them to get to know each other by using name tags and/or an icebreaker to begin class sessions.

- Incorporate “Welcoming Rituals” at the start of class, such as playing music, brief check ins with students to ask how they are doing or ask students to share something (if they choose) that happened to them that week.

- Encourage social connections by visiting discussion sections and planning outside events to encourage students to make connections with each other and the instructor.

- Share personal anecdotes and personal connections to course content, including areas where you’ve struggled, concepts you were surprised to learn, etc. to help students better relate to the course material and make real-world connections to the course material.

- Promote small group work throughout the semester and encourage students to share contact information (if they wish) on the first day in order to build a supportive network throughout the semester.

- Reduce power dynamics by sitting at the same level as your students, arranging desks or chairs in a circle (class size permitting), and/or encouraging students to lead class discussions.

- Connect or refer students to Student Accessibility Services (SAS) as needed to ensure that you are meeting the needs of all students and providing support and accommodations. For more information about Student Accessibility Services

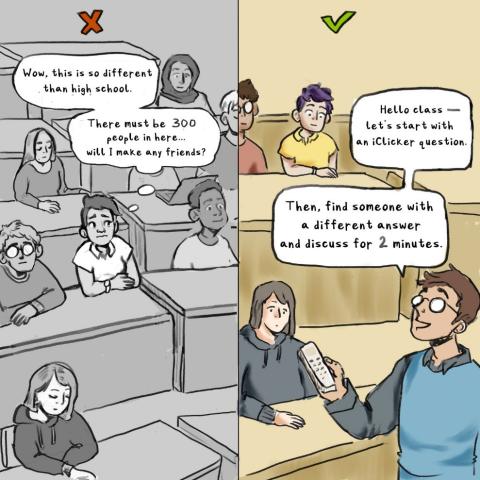

Examples to Promote Social Connections in the Classroom

“A few of my professors have made it clear that their office hours are open to anyone with any questions - whether class-related or not. Even though I never went for anything other than homework help, it was comforting to know that their door was open, and they care about their students.”

“The professor for my communications first-year seminar made the classroom environment very safe and open for asking questions and having discussions. He was also very understanding of our other commitments and allowed extensions and flexible deadlines.”

STUDENT: "Wow, this is so different than high school. There must be 300 people in here. Will I make any friends?"

FACULTY: "Hello class, let's start with an iClicker question. Then, find someone with a different answer and discuss for 2 minutes."

Incorporating Mindfulness into the Classroom

Mindfulness is the practice of being fully present and attentive to one’s inner thoughts and surroundings in an open, non-judgmental way (Kabat-Zinn, 2015). Mindfulness has been linked to many aspects of well-being, from improving memory and testing performance, reducing stress, and encouraging better physical health (Bonamo, Legerski, & Thomas, 2015; Kerrigan et al., 2017). Mindfulness practices have also been shown to assist in the adjustment and reduction of physiological stress levels in first-year college students (Ramler, Tennison, Lynch, & Murphy, 2016) and to be associated with greater psychological health and self-compassion among college students (Bergen-Cico, Possemato, & Cheon, 2013).

- Take a “Brain Break” during class sessions and encourage students to take a break from the class content, interact with classmates, stretch or engage in movement, or practice a breathing exercise. Having a consistent break time each class session helps students be aware there is a break coming and focus more intently during class.

- Provide a “Mindful Minute” at the beginning of class or before exams in which you allow students to optionally engage in deep breathing techniques or a short meditation.

- Encourage quick periods of movement for students to stretch, move around, or take a brief walk outside before resuming the material.

- Incorporate mindfulness activities during highly stressful times, such as before an exam or during midterms or final exams. This could include arranging Health & Wellness or PACS staff to present a brief in-class mindfulness exercise, encouraging students to use self-help resources available on PACS and Health & Wellness websites (see p. 36), or seeking out independent mindful moments such as through visiting a quiet space outdoors.

- Give students advance notice about which assignments may be more challenging or take longer to complete to reduce last-minute stress and help students plan.

- Consider granting an extension on an assignment to the entire class if one or more students have asked for one. If one student is overwhelmed and asks for an extension, it is likely that others feel the same way but might not feel comfortable asking for one.

- Encourage student self-care when discussing sensitive topics. It might be helpful to let students know ahead of time if you will address areas that may be challenging or traumatic. Encourage students to take classroom breaks as needed to take care of themselves.

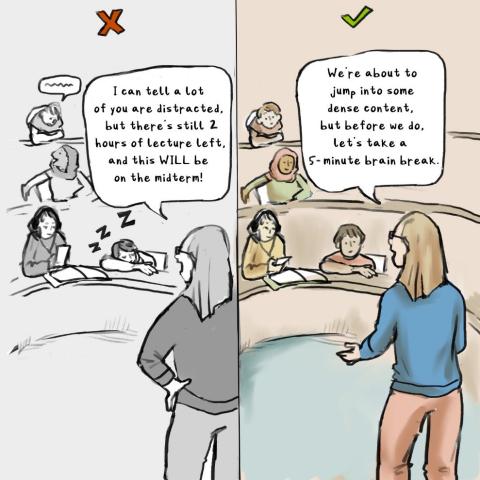

Examples of Incorporating Mindfulness

“I had a professor who would allow us to upload funny, lighthearted videos to Canvas and she would play one or two during our break halfway through class. This really eased the room during dense material and offered a time for students to collect themselves.”

DON'T: "I can tell a lot of you are distracted, but there's still 2 hours of lecture left, and this WILL be on the midterm!"

DO: "We're about to jump into some dense content, but before we do, let's take a 5-minute brain break."

Fostering Resilience and Self-Compassion

Resilience is the ability to recover from stress, despite challenging life events that would otherwise overwhelm one’s coping ability (Smith et al., 2008). More resilient students tend to have better mental health, wellness, and academic outcomes (Johnson, Taasoobshirazi, Kestler, & Cordova, 2015). Self-compassion is the practice of treating yourself as you would a friend, by accepting your personal shortcomings, but also holding oneself accountable to grow and learn from failure (Neff, 2003). Research suggests that individuals who practice self-compassion may be better able to consider failure as a learning opportunity (Neff, Hsieh, & Dejitterat, 2005).

- Talk about times you have failed, and how you worked through those failures. Help your students see how they can use mistakes and failures as learning opportunities for growth and resilience.

- Use exams and other assignments as teaching tools, rather than the “end” of learning. For example, instead of handing out grades to students, go over the exam or assignment and discuss areas of common struggle so students can learn from them.

- Consider allowing students to correct mistakes and/or re-do assignments or assessments to demonstrate continued learning and mastery of course content.

- Model how you practice compassion for yourself and others, for example sharing the strategies you use to show compassion towards yourself and colleagues (e.g., engaging with self-kindness as opposed to self-judgment).

- Share common experiences with your students, for example if a student is struggling, share about a time when you had a similar experience and learned from it.

- Be flexible, taking into consideration students’ lives outside of class and academics, including their families, children, jobs and internships, health, financial situation, other classes, etc.

- Share ways that you practice self-care in your daily life, and have students regularly share how they practice it as well. Encourage practices in the classroom to practice self-care, including allowing students to take care of their needs during class (e.g. drinking water, going to the restroom, taking regular breaks).

- Remind students that they deserve to be here at UNH. Students may be experiencing impostor syndrome and/or self-doubt due to pressure from classes and competitive academic programs. Hearing this from a faculty member or instructor can help students remember that they do belong and are able to succeed.

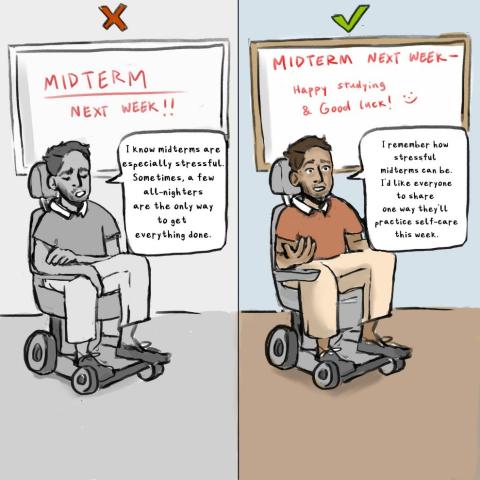

Example of Fostering Resilience and Self-Compassion

"It is helpful when instructors find a balance of attention between the professionalism of goals (academic benchmarks) and personal progress and nourishment. Also being open and reflective of one’s own struggles as a person and academic."

DON'T: "I know midterms are especially stressful. Sometimes, a few all-nighters are the only way to get everything done."

DO: "I remember how stressful midterms can be. I'd like everyone to share one way they'll practice self-care this week."

Developing a "Growth Mindset"

A “growth mindset” is the belief that talent and intellectual ability can be developed through working hard, trying new strategies, and receiving input from others—rather than being inherent characteristics (Dweck, 2016). Individuals with a growth mindset tend to achieve more than those with a “fixed mindset,” as they typically put more energy into learning (Dweck, 2016). Having a growth mindset has been shown to be positively correlated with student achievement scores (Bostwick, Collie, Martin, & Durksen, 2017) and their ability to bounce back after academic setbacks (Aditomo, 2015).

- Normalize failure by letting your students see that you make mistakes too, and modeling how they can use those mistakes to learn and grow.

- Provide space for students to struggle with concepts as a class, and encourage them to work collaboratively to work through the process.

- Focus more on learning and mastery of material, as opposed to competition and performance. Examples include: explaining what the grading curve means; being mindful that students’ perceptions of the curve can increase a sense of competition; consider allowing students to retake exams or parts of exams to learn from mistakes; having students take exams both individually and in groups; and giving students choices in how they demonstrate knowledge/mastery of content.

- Consider building in multiple ways for students to demonstrate that they have learned the course content. Examples include assigning a variety of assignment types—exams, papers, presentations, videos, etc.; allowing students to choose how they demonstrate their learning within individual assignments (e.g., multimedia/video, writing a paper, giving a presentation); allowing students to choose whether they work on assignments individually, in groups, or with partners.

Examples of Encouraging a Growth Mindset

“In lecture, the professor acknowledged that they made a mistake in the previous lecture and asked us to notify them of any future mistakes.”

“One of my instructors encouraged students to talk to her with concerns, granted extensions, and verbally acknowledged stressful times in the semester.”

DON'T: "The average midterm grade was much lower than expected. Review your incorrect answers and study harder for the exam."

DO: "The average midterm grade was much lower than expected. Maybe I didn't cover some of the material clearly, so I eliminated the questions that most of you answered incorrectly. Let's review the exam together, so we'll be ready for the final."

Identifying Students in Distress

The Students in Distress folder and the Mental Health Continuum referenced above can be useful in this regard. We recommend keeping these tools in an easy-to-access location for you to review as necessary throughout the year.

The following includes further detail on the continuum of distress, warning signs, and suggestions on how to help:

Mild Distress (“Okay”): Students may exhibit behaviors that do not disrupt others, but may indicate something is wrong and that assistance could help. Behaviors may include:

- Changes in quality of academic work, participation, and classroom engagement. At this point, these changes may or may not lead to a decline in grades or other measures of academic performance, but may simply seem different, out of character, or inconsistent.

- Unusual absences, especially if the student has previously demonstrated consistent attendance.

- Other characteristics that suggest the student is having trouble managing stress successfully (e.g., a depressed, lethargic mood; very rapid speech; swollen, red eyes; marked change in personal dress and hygiene; falling asleep during class).

Moderate Distress (“Struggling”): Students may exhibit behaviors that indicate significant emotional distress. They may be reluctant or unable to acknowledge a need for personal help. Behaviors may include:

- Repeated requests for special consideration, such as deadline extensions, especially if the student appears uncomfortable or highly emotional while disclosing the circumstances prompting the request.

- New or repeated behavior which pushes the limits of decorum, and which interferes with effective management of the immediate environment.

- Unusual or exaggerated emotional response that is inappropriate to the situation.

How to help students experiencing mild/moderate distress:

- Address the behavior/problem directly according to classroom protocol.

- Allow the student to speak freely about their current situation and the variables that may be affecting their distress.

- Consult with a colleague, department head, associate dean, Dean of Students, or a campus counseling professional.

- Refer the student to one of the university resources.

Guidelines for talking with a student with any level of distress:

- Accept and respect what is said.

- Try to focus on an aspect of the problem that is manageable.

- Avoid easy answers such as "Everything will be alright."

- Help identify resources needed to improve things.

- Help the student recall constructive methods used in the past to cope; get the person to agree to do something constructive to change things.

- Trust your insight and reactions.

- Let others know your concerns.

- Attempt to address the student's needs and seek appropriate resources.

- Do not promise secrecy or offer confidentiality.

- Encourage the student to seek help.

- Respect the student's value system, even if you don't agree.

Severe Distress (“Distressed”): Students may exhibit behaviors that signify an obvious crisis and that necessitate immediate intervention. Examples include:

- Highly disruptive behavior (e.g. hostility, aggression, violence, etc.).

- Inability to communicate clearly (garbled, slurred speech; unconnected, disjointed, or rambling thoughts).

- Loss of contact with reality (seeing or hearing things which others cannot see or hear; beliefs or actions greatly at odds with reality or probability).

- Stalking behaviors.

- Inappropriate communications (including threatening letters, e-mail messages, harassment).

- Overtly suicidal thoughts (including referring to suicide as a current option or in a written assignment).

- Threatens to harm others.

How to help students in severe distress:

- Remain calm and know whom to call for help, if necessary. Find someone to stay with the student while calls to the appropriate resources are made. See referral information in next section.

- Remember that it is NOT your responsibility to provide the professional help needed for a severely troubled/disruptive student. You need only to make the necessary call and request assistance.

- When a student expresses a direct threat to themselves or others, or acts in a bizarre, highly irrational or disruptive way, call 911 or the University Police Department: (603) 862-1427

If you are worried about a student's safety:

- When called for, let the person know you are worried about their safety and describe the behavior or situation that is worrisome to you.

- If you are concerned the student may be feeling hopeless and thinking about ending their life, ask if they are contemplating suicide. It is important to remember that talking about suicide should be taken seriously and not ignored.

- Offer yourself as a caring person until professional assistance has been obtained.

- After the student leaves your office, make some notes documenting your interactions.

- Consult with others about your experience.

Warning signs for when to refer a student for further assistance:

- Manifests a change in personality (goes from being actively involved to quiet and withdrawn or goes from being quiet to more agitated or demanding).

- Begins to display aggressive or abusive behavior to self or others; exhibits excessive risk-taking.

- Shows signs of memory loss.

- Shows loose or incoherent thought patterns, has difficulty focusing thoughts, or displays nonsensical conversation patterns.

- Exhibits behaviors or emotions that is inappropriate to the situation.

- Displays extreme suspiciousness or irrational fears of persecution; withdraws, does not allow others to be close; believes she/he is being watched, followed, etc.

- Exhibits signs of hyperactivity (unable to sit still, difficulty maintaining focus, gives the impression of going "too fast," appears agitated).

- Shows signs of depression (no visible emotions or feelings, appears lethargic, weight loss, looks exhausted and complains of sleeping poorly, displays feelings of worthlessness or self-hatred, or is apathetic about previous interests).

- Talks about unusual patterns of eating, not eating, or excessively eating.

- Shows signs of injury to self, cuts, bruises, or sprains.

- Experiences deteriorating academic performance (extended absences from class, incapacitating test anxiety, sporadic class attendance).

- Begins or increases alcohol or other drug use.

- Makes statements regarding suicide, homicide, feelings of hopelessness, or helplessness.

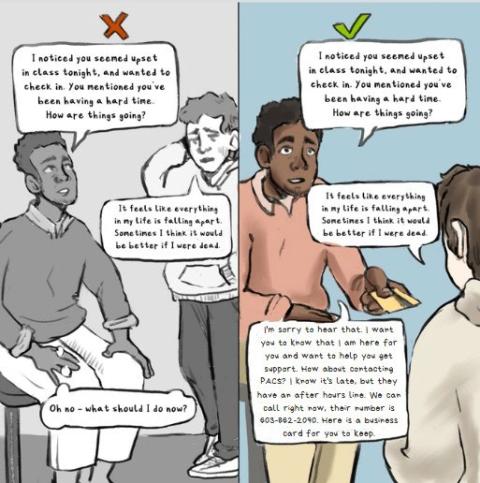

Sample Scenarios of Helping Students in Distress

“I had both professors check in on me and how I was adjusting to workloads after expressing my academic distress. My professors validated how our program is challenging.”

poor scenario:

FACULTY/STAFF: "I noticed you seemed upset in class tonight, and wanted to check in. You mentioned you've been having a hard time. How are things going?"

STUDENT: "It feels like everything in my life is falling apart. Sometimes I think it would be better if I were dead."

FACULTY: thinks to themself - oh no, what should I do now?

good scenario:

FACULTY: "I noticed you seemed upset in class tonight, and wanted to check in. You mentioned you've been having a hard time. How are things going?"

STUDENT: "It feels like everything in my life is falling apart. Sometimes I think it would be better if I were dead."

FACULTY: "I'm sorry to hear that. I want you to know that I am here for you and want to help you get support. How about contacting PACS? I know it's late, but they have an after hours line. We can call right now, their number is 603-862-2090. Here is a business card for you to keep."

Are You Concerned About a Student?

Often, you will be one of the first to find out that a student is having personal problems that are interfering with their academic success or daily life. The student may come to you for academic advising, visit during office hours, send you an email, and share personal concerns with you.

In these situations, PACS is available for assistance in a number of ways. If you would like to consult with one of our professional staff to help you figure out what steps might be taken to help the student, please call 603-862-2090 and ask to speak to the Counselor on Call.

How Do You Refer a Student to PACS?

While many students seek help on their own, your exposure to students increases the likelihood you will identify signs or behaviors of distress in a student, or that a student will ask you for help. If this occurs, you can make a referral to PACS or other resources using the following tips:

- Actively listen and validate your student's experiences.

- In addition to PACS, know about other campus resources and encourage your student to seek them out (e.g., Dean of Students Office, Health & Wellness, Student Accessibility Services, Center for Academic Resources).

- Encourage a recommendation to PACS if they are experiencing mental health distress and reassure them that it is an act of strength to seek help.

- Remind them that campus counseling resources are free and confidential.

- Mental health stigma can be a factor and your student may be ambivalent about seeking help. Exploring the PACS website together can be helpful, especially the “Meet the Staff” page.

- Sometimes students need extra support in making the next step. Ask your student if it would be helpful to walk with them to PACS to make an appointment.

What to Expect After Your Student Arrives at PACS

A front desk receptionist will greet them. The student will be scheduled for the first available Initial Consultation, which is typically available within a week of requesting the appointment (though this can change based on time of year). If the student is in crisis and needs to see someone that day, encourage them to request a Same Day Urgent appointment.

What Happens at an Initial Consultation?

The student will arrive at PACS 30 minutes prior to their scheduled appointment and will complete some electronic forms on a tablet. When they meet with a PACS clinician, the therapist will learn more about what is troubling the student and will make recommendations about best next steps (e.g., individual or group therapy at PACS or a referral to a resource on campus or in the community). It is important for members of the campus community to understand that the meetings conducted with students at PACS are confidential. Information or content of those sessions cannot be released or discussed without the student’s written permission. PACS staff adheres very strictly to ethical and legal parameters of confidentiality. Read more about student confidentiality in the next section.

How Do You Follow Up with a Student?

Depending on your role and the nature of your relationship with your student, it can be helpful to check in with them after making a referral to PACS

- Check in with your student to find out how they are doing through a follow up email, or by speaking with them after class.

- Be supportive and compassionate while remembering to maintain healthy boundaries with your student.

- If your student decided not to pursue help at this time, remind them that there are resources available to them in the future and encourage them to seek them out.

- Depending on your role, you may want to consider flexible arrangements that may be supportive to your student (e.g., extensions on assignments or exams).

Examples of How to Refer a Student

“My advisor recommended I schedule an appointment with PACS during a pretty tough time in my life. I probably would not have gone without him. Because he told me to go face-to-face and I had a strong relationship and lots of respect for him, I took his advice.”

“When I was in a bad place mentally, my TA set up a system where I had to go say hi to her before class every day. Our class met daily, so this helped me stay accountable to my own health until I could get professional help. It made me feel like someone cared about me and would notice if I didn’t show up.”

poor example:

STUDENT: "I'm struggling right now. I can't focus and I'm falling behind. What should I do?"

FACULTY: "You should go to PACS."

good example:

STUDENT: "I'm struggling right now. I can't focus and I'm falling behind. What should I do?"

FACULTY: "Thank you for sharing this with me. There are many resources available on campus. PACS offers brief therapy and crisis services focused on student mental health and well-being. Here is their information."

Standards of Confidentiality and Laws of Privileged Communications

As someone who cares about students and their well-being, it is completely understandable that you may want to know specifics regarding the services that a student might be participating in at PACS. However, as mental health-care providers, PACS is legally and ethically required to uphold standards of confidentiality and the laws regarding privileged communications, and students expect us to uphold these standards and laws.

Treating information confidentially means that PACS cannot release any protected and privileged information to professors, advisers, parents, or concerned friends without the student’s consent. Confidentiality also prohibits PACS staff from confirming that a student has made an appointment or attended sessions at PACS without the student’s explicit permission.

Our staff recognizes that this may be difficult for those concerned about a student; however, our duty is first and foremost to our student clients, and we at PACS must maintain confidentiality consistent with our professional guidelines and mental health laws. The practices and operations regarding confidentiality utilized by the PACS staff are informed and guided by law (the New Hampshire Mental Health Code), by our ethical standards within psychology, counseling, and social work, and our professional standards (via our accrediting bodies).

Without confidentiality, the therapeutic process has little chance of being effective. There are narrow exceptions to when confidentiality must be “broken” including when we consider the student-client to be a threat to self or others; when we learn of hazing or significant threats to physical property; in order to protect children or minors from current potential abuse; or if court ordered by a judge in a current proceeding.

- Check in with the student. If you have concerns about a student’s health, well-being, and/or participation in therapy, one of the ways to communicate your concern is to follow up with them. Most students consider this helpful, supportive, and caring. A simple “check in” (e.g., how is it going, did you ever have a chance to connect with someone at PACS?”) can be very supportive.

- Be aware of other campus resources, such as connecting with the Dean of Students to express your concerns about a student with them.

- For information on the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) and how it applies to you, please consult with your department or visit: https://www.unh.edu/registrar/student-records/ferpa

Examples of Respecting Confidentiality and Privacy

“One of my TA’s checked in with me repeatedly while I was in the process of getting help, listened, and asked how she could support me.”

poor example:

FACULTY CONTACTS PACS TO ENQUIRE ABOUT THE STUDENT: "I wonder if my student went to PACS after we talked last week. I'll call PACS to see if they showed up."

good example:

FACULTY CHECKs IN WITH THE STUDENT DIRECTLY: "I wanted to check in after our conversation last week. How are you doing?"

Increase Awareness and Empathy, Help Build Community

Understanding a student’s background (e.g., culture, family, academic track, multiple social identities) and developmental stage in their academic career can help bolster awareness of what students may be experiencing in the classroom, increase empathy, and help build community. Students’ comfort level in terms of disclosing may vary, which may impact their access to resources. As some students may be more or less comfortable sharing, let them know that you are supportive of them getting the help they need. While each student is unique, below are some examples of what students may be experiencing.

- First-Year Student: New geographic location, roommate relationships, transition to college, navigating independence, living on their own for the first time.

- Graduate/Professional Student: Additional responsibilities, autonomy, financial considerations, impostor syndrome, isolation, parenting and caregiving.

- Non-Traditional Student: Readjustment to academic setting, finances, worry about succeeding, developing a UNH community.

- Transfer Student: Adjusting to rigor of UNH, transition to a new setting, building community, feelings of belonging.

- Student Veteran/Military-Connected: Adjustment to civilian life, experiences of trauma, stigma around help-seeking.

- First-Generation Student: Culture shock, possible lack of support or understanding from family, pressure to succeed.

- International Student: Cost of tuition, uncertainty around jobs and visa situation, culture shock, language barriers, homesickness, challenges in or inability to return home for the holidays.

- Students with Financial Insecurity: Lack of fallback option or safety net, financial considerations, guilt associated with attending school, travel costs during breaks/holidays.

- Students of Color: Lack of representation and diversity on campus. Feeling like the “only one” in the classroom, which may increase pressure to represent an entire group and be the group’s spokesperson. Impact of micro-aggressions and macro-aggressions.

- Students with Diverse Religious/Spiritual Beliefs: Navigating the academic calendar with religious holidays, lack of representation, micro-aggressions and macro-aggressions, not knowing if there are safe spaces to practice/express beliefs.

- Gender Non-Conforming, Non-Binary, Trans Students: Navigating use of pronouns and names, self-expression, establishing community and support, micro-aggressions and macro-aggressions.

- Students with Diverse Sexual Orientations: Development of identity while navigating academic and life demands, self-expression, establishing community and support, micro-aggressions and macro-aggressions.

- Undocumented Students: Stress over immigration status and impact of political events and decisions.

- Students with Visible and Invisible Disabilities: Navigating campus and classroom environments that may not accommodate neurodiversity (e.g., ADHD, autism spectrum, learning disabilities, etc.); sensory, psychological and emotional challenges; physical disabilities; chronic health conditions.

Cultural differences around mental health and help-seeking behaviors may impact your interactions with students experiencing a mental health issue. Some students may not feel comfortable discussing mental health due to stigma, language, family messages or cultural barriers, or other factors, whereas other students may feel very comfortable doing so.

Classroom size will also impact the ways in which faculty and other instructors are able to address student mental health concerns, as it is likely easier to build community and get to know students in small discussion sections or classes as compared to large lectures. Additionally, it is important to remember that each unit/department on campus is different, and will have a different culture, expectations of success, resources, etc.

Additionally, your professional role impacts your interactions with students and your ability to address their concerns, whether you are a faculty member, lecturer, or GSI. Reflecting on your own experiences and how your background and multiple social identities affect interactions with students can be helpful. Acknowledge your role in student interactions and reflect on how it may impact your relationship with the

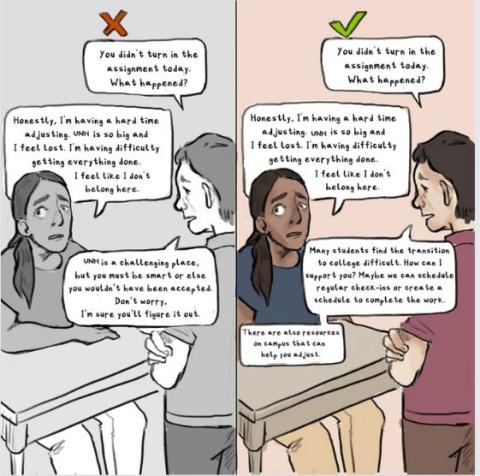

Sample Scenarios of Awareness and Empathy

“One of my professors understands that people might have unseen disabilities, cancels class during difficult weather conditions (icy sidewalks), still teaches a challenging course, but maintains mindfulness of student issues, and displays knowledge that students have individual problems.”

poor scenario:

FACULTY: "You didn't turn in the assignment today. What happened?"

STUDENT: "Honestly, I'm having a hard time adjusting. UNH is so big and I feel lost. I'm having difficulty getting everything done. I feel like I don't belong here."

FACULTY: "UNH is a challenging place, but you must be smart or else you wouldn't have been accepted. Don't worry. I'm sure you'll figure it out."

good scenario:

FACULTY: ""You didn't turn in the assignment today. What happened?"

STUDENT: "Honestly, I'm having a hard time adjusting. UNH is so big and I feel lost. I'm having difficulty getting everything done. I feel like I don't belong here."

FACULTY: "Many students find the transition to college difficult. How can I support you? Maybe we can schedule regular check-ins or create a schedule to complete the work. There are also resources on campus that can help you adjust."

For additional resources and information, please visit the How Are You – really? campaign page.

If you have questions or are unsure about a student, please call one of the resources listed below. Each of these agencies serves as consultants and resources to faculty and staff:

In case of emergency or if you feel unsafe, please call 911

University Police Department

(603) 862-1427 or 911

Dean of Students Office

(603) 862-2053

The Aulbani J. Beauregard Center for Equity, Justice, and Freedom

(The Beauregard Center)

(603) 862-5204

Office of International Students and Scholars

(603) 862-1288

The SHARPP Center for Interpersonal Violence Awareness, Prevention, and Advocacy

(603) 862-3494 – Office

(603) 862-7233 – 24/7 Helpline

Center for Academic Resources (CFAR)

(603) 862-3698

Student Accessibility Services (SAS)

(603) 862-2607

Student Emergency Funds & Resources

Food Insecurity Resources

www.unh.edu/dining/nutrition/cats-cupboard

Finding Your Community Provider Tutorial

Wellness Resources

TA’s

Faculty Mental Health

As faculty and instructors, you may also experience your own challenges with mental health and well-being. Taking care of yourself and receiving the assistance you need is an essential component of being able to be there for your students. The University provides an Employee Assistance Program for all employees and their family members. Employees can call 1-800-424-1749, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

University of Michigan Toolkit Development Process and Acknowledgments

The University of Michigan Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) and the CAPS Student Advisory Board (CAPS SAB) recognize that many of the conversations around student mental health take place outside of CAPS—between students and professors, graduate student instructors (GSIs), and lecturers. Faculty and instructors have an essential role in supporting student mental health on campus. A brief conversation between a student and a faculty member that encourages the student to get help can make all the difference in the world; an instructor who knows the resources on campus and shares that knowledge with a student can be the “tipping point” for that student to get the help they need; and emphasizing CAPS information on course syllabi as well as other communications with students can normalize help-seeking and help students not feel alone. These are just a few ways to help—there are countless others.

A committee from University of Michigan CAPS developed this Faculty Toolkit after conducting multiple focus groups and meetings with University of Michigan students, faculty, graduate student instructors, and others, in which there was an expressed desire to provide faculty and other instructors with additional resources, creative ideas, and best practices for supporting student mental health on campus.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the CAPS Student Advisory Board, a diverse group of undergraduate and graduate/professional students passionate about mental health. The CAPS SAB met over the course of an academic year and shared their student voices to provide vital content suggestions.

We are grateful to the students, faculty, GSIs, and instructors who participated in focus groups and provided invaluable feedback and guidance in developing this resource. Thank you to the Michigan Community Scholars Program (MCSP) and the Center for Research on Learning and Teaching (please refer to their Occasional Paper “Supporting Students Facing Mental Health Challenges” for valuable information on proactively supporting student mental well-being).

Special thanks to U-M School of Social Work alum, Carolyn Scorpio, for her time and dedication as Project Manager and to U-M Stamps School of Art and Design student, Jude Boudon, for their creativity and artistic talent with the illustrations.

CAPS would also like to thank the University of Texas at Austin “Well-being in Learning Environments” Project for providing a model for this toolkit.

For this second printing (October 2019), we are also grateful for the additional support given by the Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, University Health Service, the Medical School, and the Sommers Family.

REFERENCES

- Aditomo, A. (2015). Students’ Response to Academic Setback: “Growth Mindset” as a Buffer against Demotivation. International Journal of Educational Psychology, 4(2), 198–222.

- Allen, J., Robbins, S. B., Casillas, A., & Oh, I.-S. (2008). Third-Year College Retention and Transfer: Effects of Academic Performance, Motivation, and Social Connectedness. Research in Higher Education, 49(7), 647–664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-008-9098-3

- Bamber, M. D., & Kraenzle Schneider, J. (2016). Mindfulness-based meditation to decrease stress and anxiety in college students: A narrative synthesis of the research. Educational Research Review, 18, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.12.004

- Bergen-Cico, D., Possemato, K., & Cheon, S. (2013). Examining the Efficacy of a Brief Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (Brief MBSR) Program on Psychological Health. Journal of American College Health, 61(6), 348–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2013.813853

- Bonamo, K. K., Legerski, J.-P., & Thomas, K. B. (2015). The influence of a brief mindfulness exercise on encoding of novel words in female college students. Mindfulness, 6(3), 535–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0285-3

- Bostwick, K. C. P., Collie, R. J., Martin, A. J., & Durksen, T. L. (2017). Students’ growth mindsets, goals, and academic outcomes in mathematics. Zeitschrift Für Psychologie, 225(2), 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000287

- Collette, K., Armstrong, S., & Simonian Bean, C. (2018). Supporting Students Facing Mental Health Challenges (CRLT Occasional Papers No. 38). University of Michigan: Center for Research on Learning and Teaching. Retrieved from http://crlt.umich.edu/sites/default/files/resource_files/CRLT_no38.pdf

- Dvořáková, K., Kishida, M., Li, J., Elavsky, S., Broderick, P. C., Agrusti, M. R., & Greenberg, M. T. (2017). Promoting healthy transition to college through mindfulness training with first-year college students: Pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of American College Health: J of ACH, 65(4), 259–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2017.1278605

- Dweck, C. (2016, January 13). What Having a “Growth Mindset” Actually Means. Harvard Business Review, 3.

- Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: an experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 377–389.

- Hefner, J., & Eisenberg, D. (2009). Social Support and Mental Health Among College Students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 79(4), 491–499. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016918

- Johnson, M. L., Taasoobshirazi, G., Kestler, J. L., & Cordova, J. R. (2015). Models and messengers of resilience: a theoretical model of college students’ resilience, regulatory strategy use, and academic achievement. Educational Psychology, 35(7), 869–885. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2014.893560

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2015). Mindfulness. Mindfulness, 6(6), 1481–1483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0456-x

- Kerrigan, D., Chau, V., King, M., Holman, E., Joffe, A., & Sibinga, E. (2017). There is no performance, there is just this moment: The role of mindfulness instruction in promoting health and well-being among students at a highly-ranked university in the United States. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine, 22(4), 909–918. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156587217719787

- Neff, K. D., Hsieh, Y.-P., & Dejitterat, K. (2005). Self-compassion, Achievement Goals, and Coping with Academic Failure. Self and Identity, 4(3), 263–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576500444000317

- Ramler, T. R., Tennison, L. R., Lynch, J., & Murphy, P. (2016). Mindfulness and the College Transition: The Efficacy of an Adapted Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Intervention in Fostering Adjustment among First-Year Students. Mindfulness, 7(1), 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0398-3

- Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(3), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802222972

- Smith, B. W., Epstein, E. M., Ortiz, J. A., Christopher, P. J., & Tooley, E. M. (2013). The Foundations of Resilience: What Are the Critical Resources for Bouncing Back from Stress? In S. Prince-Embury & D. H. Saklofske (Eds.), Resilience in Children, Adolescents, and Adults: Translating Research into Practice (pp. 167–187). New York, NY: Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4939-3_13

- Walton, G. M., Cohen, G. L., Cwir, D., & Spencer, S. J. (2012). Mere belonging: the power of social connections. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(3), 513–532. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025731