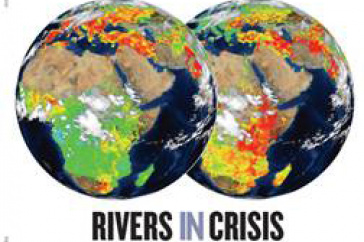

World's Rivers in State of Crisis, <em>Nature</em> Report Details

A new global analysis of threats to water security reveals widespread problems facing both humans and aquatic biodiversity. Though conditions in some rivers still appear natural, the study finds that few areas are in fact pristine, and that fundamental threat levels (left globe) are high even in areas like Western Europe where technological investments foster the perception that water security is assured (right globe) Globe image credit: Stanley Glidden, Water Systems Analysis Group University of New Hampshire. Image courtesy of Nature.

DURHAM, N.H. - Researchers from the University of New Hampshire's Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space (EOS) are contributing authors of a report published in the September 30, 2010 issue of Nature. The study finds that environmental stressors like agricultural runoff, dams, irrigation, pollution, invasive species, and fishing pressure severely threaten the security of rivers serving 80 percent of the world's population and endanger the biodiversity of 65 percent of the world's river habitats.

Rivers are the single largest renewable water resource for humans and a nursery of aquatic biodiversity. The cover-story report, entitled "Global Threats to Human Water Security and River Biodiversity," is the first global-scale synthesis to quantify such stressors on both humans and riverine biodiversity.

For the study, the international research team produced and integrated a series of 23 maps documenting the impact of these stressors using a computer-based framework they developed. Two researchers and contributing authors from the Water Systems Analysis Group (WSAG) within EOS, Alexander Prusevich and Stanley Glidden, took the lead on building the computational and visualization framework for this complex analysis. Alexander was also one of the lead designers of the mathematical formulations for the model and results validation.

"The quantification of the human impact on freshwater hydrology and ecosystems is built upon our analysis of a large array of diverse global datasets to make sure the most important anthropogenic stressors have been accounted for," says Prusevich.

Adds Glidden, "This study relies heavily on computer generated maps that give a clear view of where the areas of concern are located. From these it can be seen that New England is not immune to many of the problems outlined."

"We can no longer look at human water security and biodiversity threats independently, we need to link the two," says lead author Charles J. Vörösmarty, director of the City University of New York Environmental CrossRoads Initiative, professor of civil engineering in the Grove School of Engineering at The City College of New York, and former director of WSAG at UNH. "The systematic framework we've created allows us to look at the human and biodiversity domains on an equal playing field," Vörösmarty adds.

The framework developed through the study offers a tool for prioritizing policy and management responses to a global water crisis and, the report states, "underscores the necessity of limiting threats at their source instead of through costly remediation of symptoms to assure global water security for both humans and freshwater biodiversity."

Notes report co-leader Peter McIntyre, assistant professor of zoology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, "In the past, policymakers and researchers have been plagued by dealing with one problem at a time. A richer and more meaningful picture emerges when all threats are considered simultaneously."

Adds Prusevich, "One of the study's alarming findings was that even though highly industrialized countries such as the U.S. can alleviate potential threats with investments in water infrastructure, there is no present solution to the loss of biodiversity caused by human impact. This reduces the ability of the natural ecosystems to provide the goods and services we rely upon as a society."

Authors of the Nature report include Vörösmarty, McIntyre, Mark Gessner of the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science & Technology; David Dudgeon of the University of Hong Kong; Prusevich and Glidden of UNH; Pamela Green of the City University of New York; Stuart Bunn of Griffith University, Australia; Caroline Sullivan of Southern Cross University, Australia; Cathy Reidy Liermann of the University of Washington; and Peter Davies of the University of Western Australia.

The University of New Hampshire, founded in 1866, is a world-class public research university with the feel of a New England liberal arts college. A land, sea, and space-grant university, UNH is the state's flagship public institution, enrolling 12,200 undergraduate and 2,200 graduate students.

-30-

Image to download: http://www.eos.unh.edu/newsimage/30.9_naturecover_lg.jpg

Caption: A new global analysis of threats to water security reveals widespread problems facing both humans and aquatic biodiversity. Though conditions in some rivers still appear natural, the study finds that few areas are in fact pristine, and that fundamental threat levels (left globe) are high even in areas like Western Europe where technological investments foster the perception that water security is assured (right globe) Globe image credit: Stanley Glidden, Water Systems Analysis Group University of New Hampshire. Image courtesy of Nature.

Latest News

-

July 2, 2024

-

June 18, 2024

-

June 18, 2024

-

May 17, 2024

-

May 14, 2024