Eighteen-year-old Charlie Hood was in a hay field on his father's Derry, N.H., dairy farm when a stranger approached him with an unusual opportunity: a chance to earn a college degree.

The year was 1877, and the fledgling New Hampshire College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts was in trouble. After rising steadily in the years following the college's 1866 incorporation, enrollment had plummeted, and not a single student had showed up to register for the fall of '78. In an effort to remedy the situation, faculty members Charles Pettee and Clarence Scott had begun traveling the state by horse and buggy, distributing pamphlets about the college and talking to prospective students wherever they might be found.

It was Pettee who approached young Charlie Hood, the eldest son of an enterprising businessman named Harvey P. Hood, known as H.P., who ran a large and successful milk distribution business that covered territory from Boston to southern New Hampshire. Confident that his firstborn son had received sufficient education at Derry's Pinkerton Academy to continue the family business, H.P. showed little interest in Pettee's proposal. Mrs. Hood and Charlie, however, were convinced that a college education would be beneficial for all.

At that time, a B.S. degree at the state college could be earned in three years, and Charlie's score on the college entrance exam qualified him to enter as a second-year student. It was thus that Charles Harvey Hood became the sole member of the Class of 1880.

H.P. Hood had grown his business on his reputation for selling clean, high-quality milk, and after graduation, Charles returned to the farm with a keen interest in applying some of the scientific advancements in agriculture—specifically those concerning bacteriology—he'd studied in college. In 1888, his father made him and his brother Gilbert partners in H.P. Hood and Sons, and Charles soon became a pioneer in the sanitary production and distribution of milk, becoming one of the first to practice pasteurization, maintain laboratories for milk analysis, and employ reuseable glass bottles. Upon H.P. Hood's death in 1900, Charles became president and treasurer of the company.

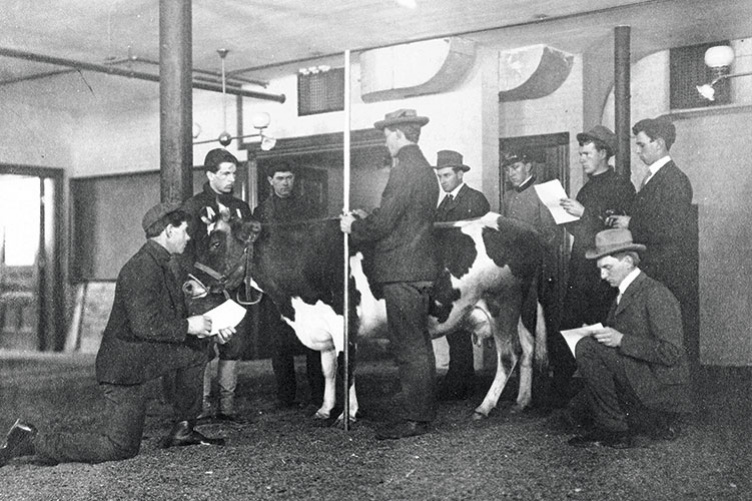

As the Hood milk business grew, so did the college—and Charles Hood's involvement with it. He remained active in the agricultural program, once offering a $50 bull from his stock to the student with the highest rank in cattle judging. In 1922, he gave the college 30 shares of H. P. Hood and Sons preferred stock, the income from which was to be used "for the encouragement, aid and benefit of deserving students." For many years, the money was used for two incentive awards, one for students who showed unusual excellence in the judging of dairy cattle, and the other for "that senior man who shows the greatest promise through character, scholarship, leadership, and usefulness to humanity." Known as the Hood Achievement Award, the latter prize is still awarded today.

On the 50th anniversary of his solo graduation, in 1930, Hood gave the University of New Hampshire its first major gift from an alumnus: $125,000 for construction and $75,000 for the maintenance of a modern infirmary. One of his requests was for a private room with a bath for the use of his mentor, Dean Charles Pettee, who still frequented his office in Thompson Hall daily.

Hood House was dedicated on June 12, 1932, and served as the campus infirmary until 1989. Hood died on November 23, 1937, at the age of 77. Dean Pettee, then 84 years old, was an honorary pallbearer at the funeral. ~

Originally published by:

UNH Magazine, Spring 2014 Issue

-

Written By:

Mylinda Woodward '97 | University Archives | mylinda.woodward@unh.edu | 603-862-1081