Lindsey Adams (green jacket) and her teammates test the strength of their truss bridge

Civil Engineering Class Tests Student Know-how

By the time Lucas Miller reached eight books, a crowd of classmates began to form around his team in the West Wing Lobby of Kingsbury Hall.

“Nine, ten, eleven…”

An admiring whisper of “That’s sick” came from the back of the room as Miller, a first-year civil engineering student from Rindge N.H., stacked 12, 13, and finally 14 copies of Strunk and White’s iconic Elements of Style neatly in the middle of a paper bridge that spanned 23 inches between two chairs. At 14 books, the bridge, which consisted of two long tubes of paper, began to buckle.

“Remember, if the bridge breaks you get no credit,” warned graduate teaching assistant and contest judge Sam White. And that was all Miller’s team needed to hear. They had to sweat through nearly a dozen other presentations, but when the final bell rang, 14 books and 23 inches proved just the right combination of strength and span to win the bridge building contest and earn an “A+” for the team.

The contest was part of associate professor Ray Cook’s introduction to civil engineering course and is intended, Cook says, “not only to get students thinking like civil engineers, but also to get them excited about doing engineering.” So, in addition to structural engineering, environmental engineering, water resources, materials, and geotechnical engineering, Cook liberally sprinkles class time with discussion of current events, such as the water shortage in the U.S. and China, and with opportunities for students to bond over challenging subject matter.

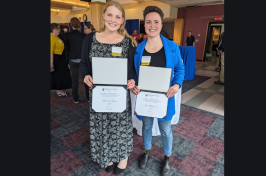

And bond they do, as on the afternoon of the contest groups huddled piecing together their 25-piece allotment of office paper with a small quantity of Scotch tape. Lindsey Adams’ team made some rapid progress on an elegant looking truss style bridge. “Basically, we were trying to find the best way to match the materials with the load,” she says. “The triangles of our bridge should spread out the support across the bridge. At least that’s the plan.” Adams’ plan was good enough to hold nine books over a 21.5-inch span — not a prize-winning result on this particular day but a very good effort.

Team Miller considered taking a “penalty” point in exchange for getting extra paper from White—a ploy that fell within the contest rules—but ultimately rejected the idea. “We focused on creating the strongest beam style bridge we could,” explains Miller. “We didn’t want to have a lot of joints that could fail.” Each section of the tube bridge had other tubes inside of it. In the middle, additional paper provided even more reinforcement.

For one day at least, in the eternal struggle of truss versus beam, beam won. But other lessons were learned by all, including how to play well with others, how to follow strict guidelines, and how to articulate the complexities of your project to a complete stranger who pesters you with questions while you’re working.

“Civil engineers have to learn how to work with planning boards, town councils, and other kinds of people,” says Cook, who won the 2012 Brierly Award for Teaching Excellence. “They have to speak well and write well as well as do the math.”

And this explains the adoption of Strunk and White’s classic as the “load” the student inventions must bear. “It’s required reading in the class,” says Miller. “We write a lot of papers.”

Bridges are like sentences: the element of style goes a long way.

Originally published by:

UNH Today