Every morning, the cows are milked at four. Every morning, the horses are fed at five. In the heat and cold. Rain or snow. In a world of health or pandemic.

“Every single day of the year, we’re here taking care of the horses,” says Brenda Hess-McAskill, the longtime manager of UNH’s equine facilities.

Even with campus quiet for an extended period of time this winter, there’s a close-knit crew of students and staff staying behind to care for the university’s herds.

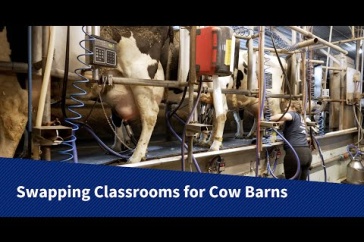

Like animal science senior Hannah Majewski, who grew up doing 4-H and started working with the campus cows her sophomore year. She’s one of four student workers who actually live above the Fairchild Dairy Teaching and Research Center, in apartments the students simply refer to as “upstairs.”

The first morning after Thanksgiving break, Majewski was up at 3:30 – as always – to milk and care for the cows. Alongside her regular litany of chores – from cleaning stalls to providing fresh grain – she’s also sure to give the cows some pampering, like scratches behind the ears.

She’s used to living on a different rhythm than her peers. Previous winters, when the beloved emails went out announcing curtailed operations for a snow day, she admits to a twinge of annoyance that she still had to get up and milk.

“It’s like getting to know a person...It’s valuable to have that with someone who isn’t a human.”

“Nothing really changes in the winter,” Majewski says. Besides, the cows actually prefer the cold to summer’s heat.

Over at the equine facilities, the horses are a bit more sensitive during the winter. Or, as Hess-McAskill puts it: horse feet are not designed for the ice.

For freshman Chloe Gross, learning each horse’s unique relationship to the cold was part of her learning curve when she started working at the barn this fall. The environmental conservation and sustainability major says the promise of structure and time spent outside pulled her to the barn as she found her footing at UNH.

The only catch was that she’d never worked with horses before. As she acclimated to the horse barn’s distinct rhythms, she also had to master the horses’ blanket preferences. There are three basic types: lightweight, medium-weight and heavy weight.

“Every horse has their blankets,” Gross says.

Even with winter’s element of unpredictability – like when McAskill goes out to get a horse and finds the snow up to her hips – the horse and dairy barns remain a hub of routine. And in a spinning world, that routine is a solace. “I just really like being at the barn,” Gross says. “Just hanging out with the horses. It makes me stronger and I can kind of forget all the craziness is going on.”

Regardless of the season or reason, the barns can be a restorative place.

“We have these amazing creatures, and we get to take care of them,” says Julia Zabkar, an equine industry and management senior. She’s worked at the horse barn since there was an opening over Thanksgiving break – her freshman year. For “animal people,” she says the normal routine is part of the magic. Her perfect day at the barn is when she doesn’t have to rush. “I can enjoy the task I’m doing and the animal I’m with. I live for those five minutes.”

So while this is a story about the humans who stay behind to care for the herds when campus empties for break, it’s also a story about the herds that care for their humans.

They have names like Darby and Giles, Otto and Cadete.

“It’s like getting to know a person,” Gross says. “It’s valuable to have that with someone who isn’t a human.”

-

Written By:

Ali Goldstein | UNH Marketing