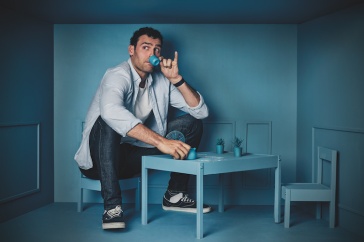

Jaed Coffin, assistant professor of creative writing

Jaed Coffin, assistant professor of creative writing, published his second book, "Roughhouse Friday: A Memoir," to critical acclaim last month. Novelist Joyce Carol Oates called it “one of the most convincing memoirs I have read tracking the mysterious course of an obsession — in this case, an obsession with fighting (i.e., “boxing”) against all odds of success and in the face of much risk.”

Coffin is no stranger to obsession, or what he prefers to call an engagement with the “ultimate and fundamental.” His first book, "A Chant to Soothe Wild Elephants," published in 2008, chronicled the summer he spent as a Buddhist monk in his mother's village in central Thailand.

"Roughhouse Friday," which covers the year he won the middleweight title of a barroom boxing show in Juneau, Alaska, would seem to be an abrupt about-face from life in a monastery.

But appearances can deceive. “On the surface it does appear as though the two topics I've chosen, monastic life and fighting, are quite opposite,” Coffin admits. “And yet, what I was searching for in both experiences was some more pure engagement with the self. What I was seeking in both was a path to clearing away all the complex storylines of my personal history — family history, cultural history, racial history — to find something more ultimate and fundamental that could guide me through the process of becoming, as a second generation son, a more complete American.”

Born to an American father and a Thai mother who had met during the Vietnam War, Coffin grew up in rural Vermont and small-town Maine. Following his parents’ divorce, he spent his childhood drifting between his father’s new white family and his mother’s Thai roots. As he emerged into young adulthood, Coffin didn’t know who he was, much less what path his life should follow. So, after college, he took to the road, working odd jobs and sleeping in his car before heading north to Alaska.

"Roughhouse Friday" tells the story of a well-educated, multicultural young man who finds himself living far from his roots and contending for the title of best boxer in southeast Alaska. But the narrative traces far more than Coffin’s fight for the championship belt. It’s about his discovery of a community in which he found himself fitting surprisingly well. It’s about confronting his own anger about his past through the lens of a new discipline that dragged the truth out of him. It’s about coming to terms with the legacy of violence and notions of masculinity he inherited from his father, the soldier.

Coffin has lectured widely at over 20 colleges and universities, where he speaks on topics of multiculturalism, masculinity and the environment. He has published more than 40 articles and essays in a broad range of journals and magazines. Perhaps it’s no surprise that he sees a parallel between writing and boxing.

“Both activities require a degree of commitment and discipline, physical and mental, that few other activities demand,” he says. “Ultimately, I find that I don't learn much unless I'm challenged by an experience in some profound way. Meditating — engaging with the very process of breath and the clearing of one's mind — can often bring up some scary stuff. Stepping into a ring against a complete stranger in the middle of barroom in Alaska can also be quite scary.”

As someone who teaches creative writing to undergraduate and graduate students alike, Coffin takes care not to zing around platitudes about the secret to writing, relying instead on some old school wisdom he learned from his mother. “The two things I have going for me that have made my writing career — and fighting career! — possible are a pretty radical work ethic and sense of self-reliance,” says Coffin.

“And those, I have no doubt, were gifted to me by my mother's example. She came to this country from Thailand, leaving her culture and language and family, and raised me on her own. And here I am. Her implicit advice: ‘Work hard, never give up.’”

-

Written By:

Dave Moore | Freelance Writer