When Darlene Dube needs to look at a particular computer programming textbook for her computer science class, she just logs on to the UNH library web site and tracks it down through one of its electronic databases. She's done it at home at night on her laptop, sipping margaritas by the pool and reading Safari Tech Books online.

A junior in her late 40s, Dube is a nontraditional geography major living in Madbury, N.H. She is also a full-time program coordinator at the UNH Complex Systems Research Center, working with scientists who research global water issues. Not only do these researchers access articles online, but the scientific journals they publish in are available through the library via a whole slew of online databases, she says. "On another level, I'm also a student here. Through digitization, professors can make certain textbooks available online for students without their needing to purchase them, and that's huge. I saved $30 to $50 reading this textbook online."

The digitization Dube is talking about is a phenomenon that has utterly transformed the way we acquire information. At the UNH Library, the revolution has changed the way pictures, music, and the text in books, journals and newspapers are stored and disseminated. It is putting access to a whole universe of knowledge at a user's fingertips, including books and journals UNH doesn't actually have.

"Everything is different," says Claudia Morner, dean of the University Library, gazing out of her office at a vista of brick academic buildings. "Yes, we're still buying books and periodicals and checking books out. But we're using technology a lot more than we used to, and that's really changed what it means to work and study here."

Many professors and alums can remember the sudden freedom from having to rummage through dog-eared index cards and jot down Dewey Decimal System numbers to track down books when the library card catalogue went online in the late 1980s. That marked the beginning of computerization at the library. Digitization—based on digital imaging technology—is putting information into electronic form so it can be retrieved by computer or online, and the National Science Foundation declared the first Digital Library Initiative as long ago as 1993. But in the last decade, the pace and the volume of digitization have picked up.

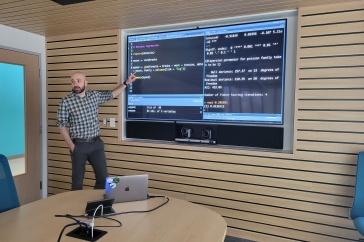

UNH digital collections librarian Eleta Exline stands at a library computer and demonstrates. Around her, computers hum and keyboards tap as students check e-mail, work on assignments and study for exams, all online. Exline clicks her mouse, and up pops a collection of early New Hampshire broadsides and proclamations. Their decrepit yellow pages, frayed edges and all, hover on the screen, denouncing heresy and inciting fasting.

At Exline's command, the broadsides disappear, replaced by the image of a boy shaped like farm animals squashed together. This is "The Boy Made of Meat," a curious poem by a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet that went unpublished until a passionate New Hampshire educator, the late William Ewert '65, '69G, discovered it and published it himself. The cover shows the reddish boy—part fish, part sheep, part chicken. Another click, and up pops a hand-scrawled lamentation by poet W.D. Snodgrass about all the meat boys are forced to consume to become men.

Next is a black-and-white photo of Ralph Page, dean of New Hampshire contradance callers. On the screen is the worn cover of the first issue of Northern Junket, a periodical Page single-handedly edited in wobbly handwriting for all to see: Vol. 1, No. 1, April 1949.

And those are just a few snippets from the library's online collections. Today's digitized library offers UNH students and faculty members a dizzying array of ways to get data. These include electronic databases, from MathSciNet to The New York Times back to its start in 1851.

Although the concept is still in its infancy, there are also thousands of classic e-books available free in the public domain, says Morner. Alumni from even as recently as the '90s can probably remember when they would go to the library for a book on reserve and find all the copies had been checked out. In the digitized library, professors can put a book on electronic reserve. Today, UNH faculty and staff members and students have online access to 21,000 periodicals. The library still subscribes to 5,333 print periodicals and another 20,000 government documents, but the use of paper periodicals and newspapers is plummeting. While the number of books put on reserve dropped nine percent in 2005 from the year before, electronic material on reserve for student use increased by 25 percent.

David Watters can remember toiling in the semi-darkness of a "cavelike" back room in the library, hunched over aging microcard machines to read early copies of the New England Primer, the first American schoolbook. Back then, microcards reproduced the book on postcard-sized cards. Watters, a UNH English professor, spent almost a year laboriously feeding the cards into the machine and holding each one down on the lens so it would be in focus, struggling to take notes with his other hand. It was "appalling," he says, and almost impossible to get students to use the machines.

Today, Watters has instant online access to all the books printed in America before 1800, and everything from temperance to witchcraft. With a few more clicks, images of pages of The New England Primer bloom on his computer screen. And he can search them too. "Let's say I was interested in attitudes toward the deaths of children, as a person interested in New England gravestones," says Watters, who directs the Center for New England Culture at UNH. "I can search for gravestones and death, and every little rhyme and poem about it, every prayer or dialogue in the primer is suddenly produced." He can download an issue for his students to read or tell them to log on and go read it. "The learning experience is so much more exciting today because it's immediate," he says.

Physically, Dimond Library reflects the technology that has changed it. As part of its renovation eight years ago, it was wired with jacks for Internet access and 18 computers for public use.

Then wireless Internet access came along. Today, the library has 144 public computers, and all its student study spaces have wireless access. The reserve desk loans out 15 wireless laptops, four hours at a time, to students and faculty members.

Today, most UNH students come from a world in which digitization is a given. Junior Elizabeth Summers routinely checks from her computer to see if reserve books are available, so she doesn't waste time trekking to the library. A sociology major, Summers doesn't even bother with the library's periodical room because everything she wants is on EBSCOhost, a company that provides an electronic database of scores of thousands of academic journals and magazine articles. "It's insanely helpful," says Summers. For example, in order to build a graph of the relationship between runaway teens and family ties for her sociology of statistics class, she sorted through 50 hits to choose the 20 most relevant articles.

Summers says she still uses books, but she adds, "there are definitely people who don't." In many ways, UNH is becoming a paperless school. Grades are posted online in the password-protected Blackboard, an online course management system. There are no bills, just reminders e-mailed to students and authorized payers. Most teachers don't give out a syllabus on paper—it's all on Blackboard.

Just before spring break, Adam Karr, a junior psychology major, sat at one of the library's computers preparing for a statistics exam by checking out a sample test his professor had posted on Blackboard. There he can also check due dates, read class notes, view slides or PowerPoint presentations, or e-mail professors. Junior Emily Todd is majoring in history and uses her student ID number to access library databases from home. "It's very helpful because I live off-campus," she says.

Bill Ross, the head of Special Collections, says digitization has turned the library from a repository into a doorway to information. "To my mind, it's no longer important what you own, but what you provide access to," says Ross, who chairs the Digital Library Committee. "Because what you need is the information. Who cares who owns it?" If you can get an article from Document Delivery, if you can borrow a book from the Boston Library Consortium, he argues, referring to different ways to get information that is not physically at the library, it's no longer as important for the library to try to buy all the books and periodicals it might once have thought necessary.

Still, Morner does not see any end to storing books and papers. "I don't think we're going to have a bookless library," she says. For one thing, not everything in the library is available online. For another, there is not a consensus that digital is in every way superior to print. On a more pragmatic level, Morner eyes the morning hubbub of students and notes, "This place is mobbed and very, very popular." But the library is moving towards a time when current periodicals may not be in paper form, she says, as more and more are online.

As more of the library's own possessions are scanned and posted online, students need help finding things. "If you needed the address of a publisher 10 or 20 years ago, you might have called the reference desk," says Morner. "Now, you use Google. Questions tend to be fewer, but more complicated, and students often need help figuring them out."

While students can get more information faster, the downside is "it's hard to wade through all that and evaluate what you're looking at," Morner says. And she frets that often students are under the impression that if something is online, it's more valid than something published in a book. "They have to be taught to discriminate," she says, and UNH reference librarians offer students classes and individual tutoring sessions, and answer e-mails on how to hunt for information and how to judge what's good information and what's not. Today, library staffers spend more time helping students access online databases and e-journals than finding paper books, Morner says.

Roland Goodbody '82, manuscripts curator in Special Collections, says a big part of what he does is "helping kids find stuff." An example is the Clamshell Alliance Collection, he says, referring to documents on the group's epic 17-year battle—starting in the '70s—against the Seabrook nuclear power plant, a collection that could be headed for digitization. When he helps orient a class on grassroots organizations and the media, public opinion and mass communication, Goodbody has to remind himself that these students weren't born at the start of that fight.

One downside of digitization is that it makes plagiarism easier. With cutting and pasting so effortless, and the existence of paper- and essay-mills online, UNH has been testing out two plagiarism detection software packages, SafeAssignment and Turnitin, that compare a student's work against a wide range of sources.

Money is a problem, too. In 1997, the library spent $60,000 on its first online databases from EBSCO Publishing, an Ipswich, Mass.-based company managed by Tim Collins '85. Now the library spends more than $1,000,000 a year on e-databases and peer-reviewed electronic journals—a cost that does not include giving access to off-campus alumni, which would increase the expense considerably.

With the cost of print subscriptions skyrocketing as well, UNH has joined a national movement of colleges fighting higher costs by creating free institutional repositories for faculty-written articles. Meanwhile, the art department wants its slide collection online. "The Honors Program has approached us about posting honors theses," Morner says. It would be useful to juniors, who "don't really know what an honors thesis looks like."

So vast is the mass of electronic data that the library is installing DigiTool, a digital collections management program. Next year, the plan is to follow this with MetaLib, a powerful search tool. The project is funded by $310,000 from the University System of New Hampshire to put online music, photos, film, rare books and manuscripts no longer protected by copyright.

Digitization is also changing the way scholars do research. When UNH psychology professor Ellen Cohn used to search for articles on delinquency 28 years ago, she'd wade through volume after volume of indexes of abstracts, and hope the library had the journals she wanted. Today, Cohn uses Web of Science, an interdisciplinary electronic database of scholarly journals. "It's an amazing time-saver," says Cohn, Lamberton Professor of Criminology and coordinator of the Justice Studies program.

Eliga Gould spent two years in the dark bowels of the old British Library in London and the Huntington Library in California, poring through a thousand aged and yellowed Revolutionary War-era pamphlets to research his first book. Today, the associate history professor could do much of that from his computer.

Eliga Gould spent two years in the dark bowels of the old British Library in London and the Huntington Library in California, poring through a thousand aged and yellowed Revolutionary War-era pamphlets to research his first book. Today, the associate history professor could do much of that from his computer.

Some say digitization and technology have also multiplied opportunities for confusion and duplication of information. Ross of Special Collection says the sheer volume of data is forcing the library to make tough choices. The library has hired consultants to help it assess the library's current status, users' needs and how best to meet them. "We're at the stage where we're establishing new priorities," says Ross. "Although it seems different, you still have a lot of the same concerns. It needs to be a meaningful collection and usable to people."