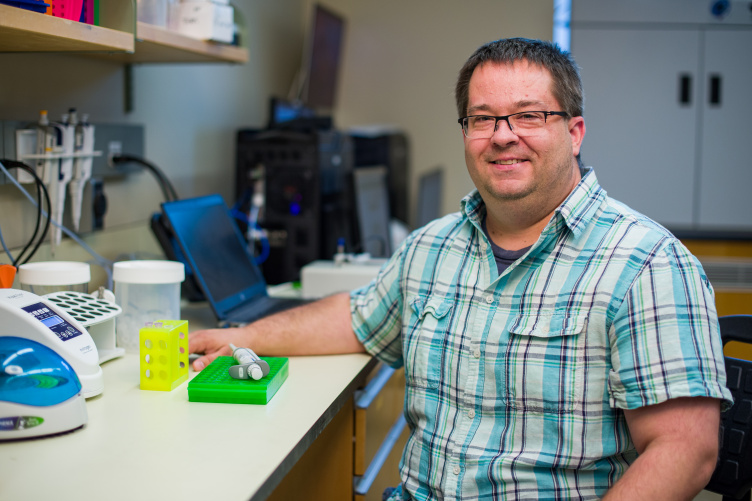

Matt MacManes, the first-ever UNH recipient of the NIH's prestigious Maximizing Investigators' Research Award, will study a desert rodent to better understand how humans could survive dehydration.

A major National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant will help a University of New Hampshire researcher understand dehydration by studying a tiny desert rodent that’s adapted to survive both acute and chronic dehydration. The five-year award to Matthew MacManes, assistant professor of genome-enabled biology at UNH, will advance his work with the cactus mouse that could lead to helping humans better survive dehydration.

“Understanding how mice survive dehydration may help us understand why humans don’t survive it and maybe how we could help them.”

“We know that many people suffer from dehydration, from the elderly to soldiers in desert wars to the many people worldwide without access to clean water,” MacManes says. “Understanding how mice survive dehydration may help us understand why humans don’t survive it and maybe how we could help them.”

MacManes’s NIH Maximizing Investigators’ Research Award (MIRA) is for $1.7 million. “It’s a big award that’s going to support a lot of cool science,” he says.

“This is a very prestigious award. This career-changing NIH grant will significantly advance Matt’s important work in understanding dehydration,” says Jan Nisbet, senior vice provost for research at UNH. “I congratulate him and look forward to the results of his research.”

With the grant, MacManes and his team — the award will fund a postdoctoral researcher, several graduate students and many undergraduate researchers — will study the physiology and genomics of cactus mice, Peromyscus eremicus, in both the field and the lab.

Fieldwork will take his team to the southern California desert, where they’ll capture mice and study their physiology — mainly electrolytes and urine concentrations (the mice don’t produce much or any urine, but MacManes says sometimes “you can collect a drop or two of a viscous, tar-like substance”). They’ll also look at population genomics to try to understand which parts of the genome are involved in helping the mice adapt to the desert.

Back in the lab, researchers will monitor captive mice’s metabolic rates, blood pressure and heart rate under different hydration scenarios for a deeper exploration of the physical response to dehydration. MacManes is homing in on how the mice maintain blood pressure in their kidneys when they’re severely dehydrated, as kidney failure is a serious impact of dehydration in humans.

“There’s a molecule that seems to preserve blood pressure in their kidneys, and we can pharmacologically manipulate this molecule to study its role in protecting the kidneys,” he says. He’ll also be looking at the influence of diet — proteins and carbohydrates — on dehydration. Because we know so much about nutrition, this line of inquiry shows promise, he says.

“What if we could help soldiers, or other people who have to work in hot, dry environments, survive dehydration by feeding them a particular diet?” MacManes says of his long-term goals.

MacManes notes this work is particularly relevant in a changing climate that’s predicted to make much of the Earth, particularly North America, hotter and drier. “There are lots of places on the Earth where there will continue to be fresh water, but we can’t all move there,” he says.

“This is the first NIH MIRA award received at UNH,” says Jon Wraith, dean of the College of Life Sciences and Agriculture. “The goal of this program is to increase the efficiency of NIH funding by providing capable investigators with greater stability and flexibility, thereby enhancing scientific productivity and the chances for important breakthroughs. The program is also intended to help distribute funding more widely among the nation's highly talented and promising investigators. We’re very excited that Dr. MacManes has been recognized by the NIH as among that group.”

Contact Matt MacManes via @MacManes on Twitter or Matthew.MacManes@unh.edu. Regular updates to this project will be posted to his lab website.

-

Written By:

Beth Potier | UNH Marketing | beth.potier@unh.edu | 2-1566