Key Finding:

In a study of the activity of 12 mammal species in rural versus suburban areas in New Hampshire, researchers found that bobcats and lagomorphs (rabbits and hares) reduced their activity in suburban areas, while deer and coyotes shifted to being more active at night. The study results highlight how mammals change their behavior in complex ways to adapt to growing suburban development.

Key Terms:

Camera traps: Motion-activated cameras that are used to capture images or video of wildlife. More information

Characteristics of wildlife camera traps include:

- Motion-triggered to activate when an animal passes in front of the camera.

- Infrared sensors to detect animals day or night.

- Mounted to trees about 50 cm above the ground and angled facing north.

- Unbaited to avoid attracting animals deliberately.

- Viewshed in front cleared to reduce false triggers from vegetation.

Exurbanization: The growth of low-density, semi-rural housing and communities outside of major urban centers, resulting in development and human populations spreading into previously undeveloped areas. This creates an exurban matrix of housing mixed with patches of natural land.

Habitat fragmentation: The division and isolating of habitats into fragmented patches due to expanding human development and infrastructure, like what occurs with exurbanization. This divides and shrinks the intact habitats that wildlife relies on.

New research by New Hampshire Agricultural Experiment Station scientist Remington Moll looks at how some of the Granite State’s mammals respond behaviorally as people from urban areas increasingly move to rural areas, leading to changes in housing density and habitats. In a recently published paper in the Journal of Urban Ecology, Moll, along with lead author and UNH graduate research assistant Mairi Poisson ’23G, UNH graduate research assistant Andrew Butler ’11, and their partners from New Hampshire Fish and Game, find that mammals change their behavior in complex ways to adapt to growing rural development. Ultimately, their findings indicate that mammals alter their behaviors to adjust to expanding development, which could act as early warning signs of future population impacts.

As Granite Staters move out of New Hampshire cities into more suburban communities and more affordable housing, it’s led to increased development in previously rural areas, transforming these zones into exurbs — area outside the city that are less densely populated than suburbs, but more dense than rural sections. Not much is known yet about the behavioral responses of mammals to the changing habitat as it becomes more fragmented, largely by residential housing. To better understand the impact on mammals, the team studied their activity levels and patterns, specifically comparing activity in rural versus suburban areas.

A Behavioral Response by Granite State Mammals to Exurbanization

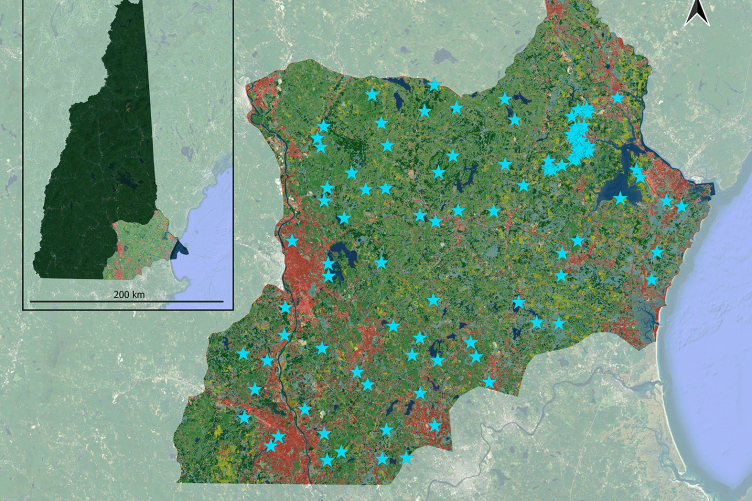

The researchers used 104 motion-activated cameras placed in rural and suburban locations in the Seacoast and Southeastern parts of New Hampshire to photograph mammals over time. The cameras automatically took pictures of animals whenever they came into view. The team focused their study on 13 mammal species detected frequently enough to study: bobcat, coyote, fisher, white-tailed deer, red fox, gray fox, Eastern striped skunk, Eastern cottontail rabbit, Virginia opossum, raccoon, North American porcupine and snowshoe hare.

Figure 1 illustrates the study area located in New Hampshire, USA. Researchers placed 104 camera trap sites (indicated by blue stars) across the region, spanning both exurban and rural zones. The central section is mainly rural and characterized by its native vegetation, primarily composed of mixed forests. In contrast, the eastern and western edges of the area are marked by significant urban development. The map depicting the study area's layout is based on the 2019 NLCD (National Land Cover Database) as sourced from Dewitz (2021).

The researchers analyzed the timing of the camera images to see if mammal activity levels and daily patterns differed between rural and suburban sites, and they tested hypotheses about whether species with larger ranges or more daytime activity would change behaviors more in suburban areas.

The team identified both species- and season-specific responses to exurbanization by the animals studied, explained Poisson, and discovered that there wasn’t any uniform response to exurbanization across the entire mammal community.

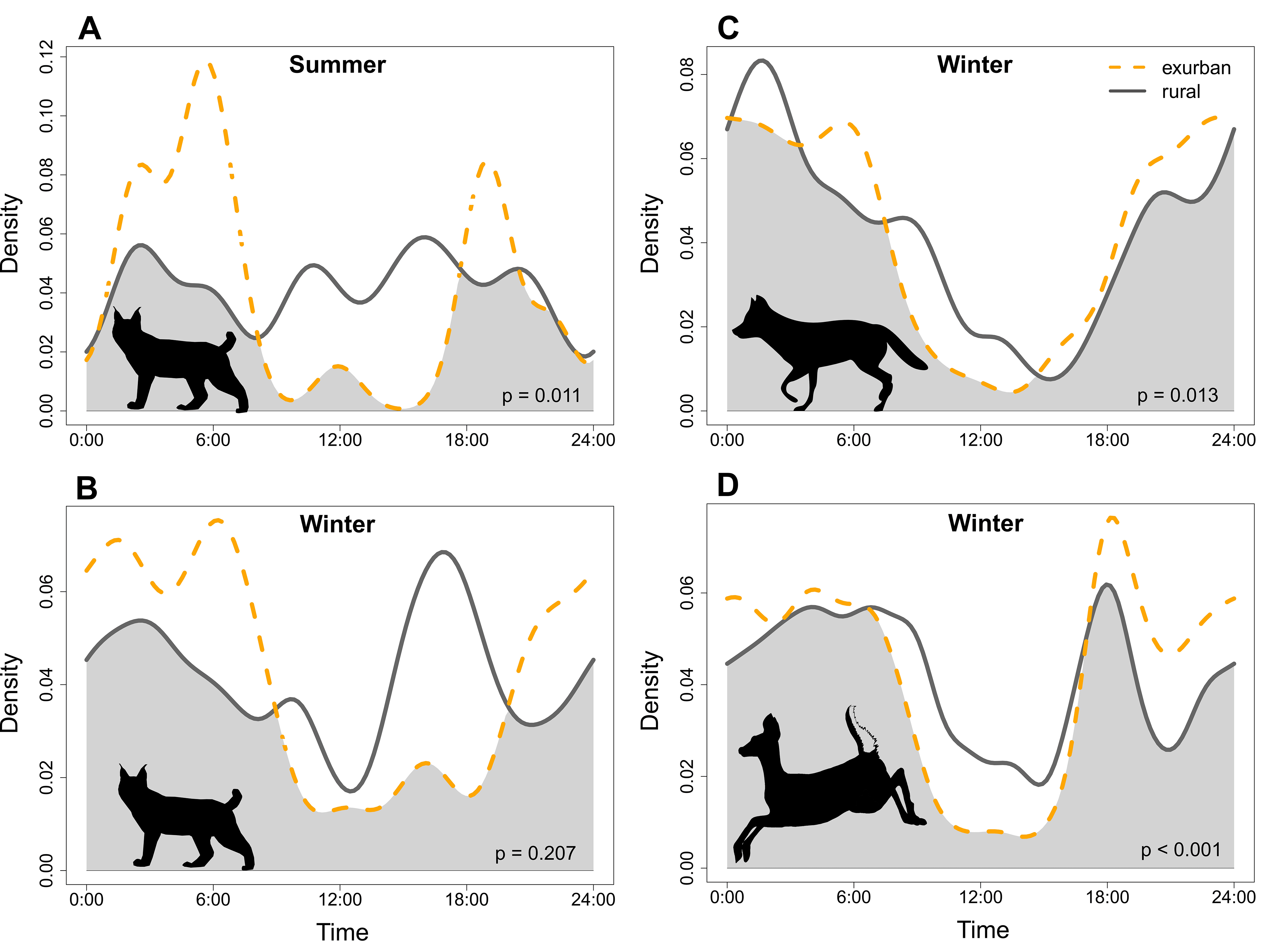

“Some species, like the white-tailed deer, reduced their overall activity in exurban areas in the winter but not in the summer,” Poisson said. “In terms of activity patterns, some species did become more nocturnal in response to exurbanization, like bobcats, while others actually shifted away from nocturnality, like the fisher during summers.”

Additional observations included that bobcats and rabbits significantly reduced their activity in exurban areas during the summer, while coyotes and deer became more nocturnal. The diverse responses in New Hampshire mammals highlight the complicated interplay between wildlife and human settlements spreading into rural areas.

Figure 2 displays the activity patterns of various animals in different seasons and habitats. Activity patterns for bobcats during both summer (A) and winter (B), as well as coyotes (C) and white-tailed deer (D) during winter, were analyzed. This was done using data from camera trap detections in southeastern New Hampshire, USA, during summer 2021 and winter 2021–2. The study differentiated between exurban areas (marked by yellow dashed lines) and rural areas (represented by gray solid lines). Among these species, all of them exhibited statistically significant variations in their activity patterns, with the exception of bobcat winter activity patterns.

“The research sheds light on species-specific behavioral changes that could affect mammal communities as rural landscapes become more developed,” said Moll. “Changes in activity behavior could be an early warning signal for future population declines, or it could simply indicate that these species are able to successfully adapt to exurbanization by altering their behaviors.”

Future research by Moll and his team will focus on identifying whether behavior changes indicate either adaptation or possible population decline.

“Either way, understanding these complex wildlife adaptations will be key for managing mammal populations amidst expanding suburbs,” he added.

Exurbanization in New Hampshire

The Granite State remains one of the more rural states, with 25 areas designated as “urban” by the U.S. Census Bureau, i.e., densely developed residential, commercial and/or nonresidential urban areas that contain at least 2,000 housing units and at least 5,000 people. Conversely, roughly half the state lives in rural communities, where the average population density is about 47 people per square mile. The 2020 Census also identified 25 areas around the state as “urbanized” or “urban clusters”—often encompassing the growing suburbs in and around cities. It’s in and near these “exurban” locations—low-density, semi-rural housing and communities outside of major urban centers—which are experiencing rapid growth in New Hampshire. And it’s in these where less is known about the behavioral responses of mammals to the changing habitat as it becomes more fragmented largely by residential housing.

This material is based on work supported by the NH Agricultural Experiment Station through joint funding from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (under Hatch award number 1024128) and the state of New Hampshire. Additional funding was provided via the Pittman-Robertson Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act Grant No. F21AF01526 (W-112-R-1), the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department and the University of New Hampshire.

This work is co-authored by Mairi Poisson ’23G, Andrew Butler ’11, Patrick Tate ’99 ’07G, Daniel Bergeron ’11G and Remington Moll.

You can read the published article, Species-specific responses of mammal activity to exurbanization in New Hampshire, USA, in the latest issue of Journal of Urban Ecology.

-

Written By:

Nicholas Gosling '06 | COLSA/NH Agricultural Experiment Station | nicholas.gosling@unh.edu