Photos by Elizabeth Weidner '22G.

In December 2023, thanks to UNH, the United States grew by one million square kilometers.

The U.S. gained that seabed territory beyond 200 nautical miles from our coasts through a geopolitical process called the Extended Continental Shelf. To satisfy its requirements, the federal government turned to a team of the nation’s top ocean mappers: those at UNH.

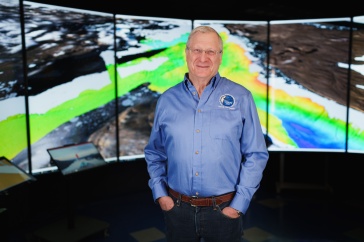

“The mapping done by UNH led to the increase in the size of the U.S.,” says Larry Mayer, director of UNH’s Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping (CCOM). It’s a bold claim, but Mayer has every reason to boast. In its 25 years, CCOM and its sister NOAA partnership, the Joint Hydrographic Center (JHC), have become the world leader in both how we map the deep and who conducts that exploration.

The UNH team — Elizabeth Weidner ’22G, CCOM associate director Brian Calder and CCOM director Larry Mayer — take in the Arctic scenery from the icebreaker Oden

.

The UNH center has developed the fundamental technology that helps us map the seafloor and understand what the data tells us. Many of the 238 graduates of its master’s, Ph.D. and certificate programs lead hydrographic agencies and ocean mapping efforts across the globe. CCOM researchers and students are aboard seafloor mapping missions around the world, from Arctic Greenland to the South Pacific to the nearby Gulf of Maine on board the CCOM research vessel Gulf Surveyor, purpose-built for ocean mapping.

CCOM began in 1999, when hydrography — the collection of data to create navigation charts — was on the brink of a major advance. The field was transitioning from relying on data collected from single sonar beams bouncing off the seafloor to the far more efficient multibeam echosounding. Mayer and colleagues, then at the University of New Brunswick in Canada, were pioneering the adoption of this new technology.

Seeking to build this capacity in the U.S., NOAA turned to UNH for a partnership that launched the Joint Hydrographic Center. Co-directed from the start by Mayer with Andy Armstrong, then a NOAA officer, the JHC exists in parallel with CCOM at UNH, serving NOAA’s needs to create navigational charts.

But it was never just about making maps. “From the beginning, Larry and the faculty here had other visions,” says Armstrong, who remains the NOAA co-director of the JHC.

Why Map?

“We know more about the surface of Mars than we do the seafloor,” Mayer is fond of saying. Just 26% of the world’s ocean floors have been mapped to high resolution.

There are many reasons, he says, to better understand the global seafloor: Safe navigation first and foremost, but also the search for resources, infrastructure like cables and pipelines, modeling deadly storm surge and tsunamis and understanding (and protecting) ecosystems. Even our changing climate is driven by the shape of the seafloor and how ocean currents move across it.

KNOW YOUR OCEAN VOCABULARY

Hydrography

Collecting physical data about the seafloor and coast to create charts for safe navigation.

Ocean mapping

A broader enterprise, encompassing mapping to understand the dynamics of the sea floor, the composition of the sea floor and even what’s happening in the water column.

Water column

A vertical section of sea extending from surface to the ocean floor.

Bathymetry

Measurement of depth in bodies of water; the same way we talk about topography for land.

Echosounding

Technique that determines the depth of a body of water by transmitting sound waves through the water and measuring the interval of time it takes the “echo” to come back to the source.

For all the practical, globally consequential reasons to map the ocean, Mayer’s favorite is one far less tangible: exploration.

“Because who knows what we’re going to find? The most exciting discovery is the one we haven’t made yet,” he says.

In September 2024, that impulse for exploration took Mayer, CCOM Associate Director Brian Calder and Ph.D. alumna Elizabeth Weidner ’22 to northern Greenland on the icebreaker Oden, where their mapping efforts will enhance understanding of the effects of climate change on global sea-level rise.

On board the first modern vessel to navigate the remote Victoria Fjord, the CCOM researchers made history — and memories. “On more than one occasion Brian … turned to me and said with genuine amazement, ‘We get paid to do this,” Weidner recalls.

Even Mayer, who estimates he’s spent nearly seven years at sea, calls the icy landscape “some of the most remarkable scenery and lighting I have ever seen.”

The most satisfying mapping mission of Mayer’s UNH career was not a seafloor mapping effort at all. During the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, Mayer and others from CCOM were called into service to train their sonar on the water column — the conceptual “column” of water that reaches from the seafloor to the surface — to detect oil and gas that might be leaking from the area around the wellhead.

“I go up to the Arctic and I know we’re working on super, super important climate problems, and I know that every day here we do things that improve safety and navigation,” he says. “But with Deepwater Horizon, on a day-to-day basis, we really knew that we were serving the country.”

Partnering with Industry — and Robots

CCOM is a leading partner in Seabed 2030, a global initiative to create a complete map of the ocean floor by the beginning of the next decade. It’s an ambitious goal, with 74% of the area unmapped, but in the quest to achieve it, CCOM is deploying a secret weapon: robots.

Continually evolving their independence from human operators aboard ships or nearby on shore, these uncrewed mapping vessels, working like oceangoing Roombas, increase efficiency while decreasing costs.

The star robot of the moment is DriX, a speedy, long- endurance, 25-foot-long red autonomous surface vessel (ASV) whose sleek hull and distinctive “sail” give it the appearance of a submarine. Born at the French technology company Exail, DriX has been used and tested by CCOM since 2018 and is continuing to mature with robust collaboration between Exail, UNH and other partners.

“We take the bruises on learning how these new systems work or don’t work, so by the time it gets to NOAA or other customers, all the systems are worked out,” Mayer explains.

Marine Slingue, Exail Americas president, calls CCOM “a fearless innovator, working out the nitty gritty of new functionalities. CCOM provides us with invaluable feedback on operations, and this close collaboration enables us to continuously enhance the DriX.”

Seafloor Systems Echoboat, a remote- controlled vessel, helps the UNH team map the seafloor of Victoria Fjord in northern Greenland.

Recently, researchers and technicians from CCOM, Exail, NOAA and other government agencies conducted a “dual DriX” experiment that tested the possibility of sending two uncrewed systems, operated from shore, out to sea. The exercise exemplified the value of CCOM’s partnership with Exail as well as with NOAA.

“They’re not afraid of pushing the limits,” Slingue says of CCOM researchers. “It’s not just about the DriX working and doing the mapping — it’s about exploring new ways of doing things. Their forward- thinking approach drives progress and inspires improvement.”

CCOM maintains symbiotic relationships like these with 60-plus industrial partners. The Exail collaboration, begun in 2018, is among the deepest, with Exail opening its Marine Autonomy Innovation Hub at UNH in 2023. Envisioned as the company’s base for U.S. operations, the hub is currently in UNH’s John Olson Advanced Manufacturing Center and will move to the future NOAA Center of Excellence for Operational Ocean and Great Lakes Mapping to be housed at the Edge, UNH’s forthcoming innovation neighborhood on the west edge of campus.

Access to CCOM’s technological contributions extends far beyond these formal partnerships. The center has led development of software that makes sense of the massive amounts of data delivered by multibeam sonar, with innovations based on research from Calder, now the industry standard.

Mapping and Mentoring

For all its boundary-pushing achievements, Mayer is unequivocal about CCOM’s primary impact on our understanding of the world’s oceans.

“Our biggest contribution is the students we’ve graduated,” he says.

The hundreds of alumni extend CCOM’s reach across the globe, where they lead hydrographic agencies, navies and related industries or work in academia. The center hosts the Nippon Foundation/ GEBCO (General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans) training program, a one-year fellowship for scientists from around the world, primarily developing nations, to level up their ocean mapping skills.

HOW DID YOU FIND YOUR SPARK?

Larry Mayer

When I was about 7 years old, I lived in the Bronx and would visit my grandfather who ran a laundry in Manhattan. Next to the laundry was a sporting goods store that had some of the first retail SCUBA gear (Aqualungs) on display. I was intrigued and my grandfather bought me a book called “Boy Beneath the Sea” by Arthur C. Clarke, about a young boy SCUBA diving around Ceylon [now Sri Lanka]. I was hooked. Then I found Jacques Cousteau in National Geographic and on TV and I never looked back.

Weidner, who shared mapping duties with Mayer and Calder in Arctic Greenland, describes the expertise and access CCOM afforded her as unparalleled.

“Not only are [CCOM faculty] the experts in what’s new, but they have developed the field as a whole,” she says. “And everybody is connected to CCOM. By the time you finish your time there, you meet everybody who is at the forefront."

Weidner is taking her own place at the forefront, recently joining the marine sciences faculty at the University of Connecticut.

As CCOM continues to dominate the field of ocean mapping, Mayer notes why mapping an entity that covers most of our planet merits this all-hands-on- deck approach.

“Mapping is always the first step,” he says, pointing out those million square kilometers and the resources our nation can now claim. “When Lewis and Clark went out, what did they do? They went out to map. That’s how you explore: you understand your spatial context.”

-

Written By:

Beth Potier | UNH Marketing | beth.potier@unh.edu | 2-1566