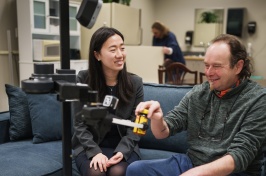

David Plachetzki samples marine invertebrates from the research pier at UNH's Coastal Marine Laboratory. Ongoing research in the lab seeks to understand the sensory biology of marine invertebrates across life history.

David Plachetzki, an associate professor in the department of molecular, cellular, and biomedical sciences, has spent the last decade at UNH advancing genetics research. With a focus on interdisciplinary work, Plachetzki combines molecular biology with computational genomics to study how complex traits such as the senses, microbiomes or defense mechanisms have evolved over millions of years. His research sheds light on the genetic origins of these sensory systems, which are essential for survival, and his work on the slime defense mechanisms of hagfish has drawn interest from defense strategists.

In addition to his lab work, Plachetzki conducts field research, collecting marine specimens through SCUBA diving expeditions in the Gulf of Maine, Caribbean and Galapagos Islands. These hands-on efforts enhance his studies of marine life and contribute to his understanding of evolutionary processes. Whether he is analyzing genomes or mentoring future scientists, Plachetzki continues to explore fundamental questions about biology.

COLSA: How long have you worked at UNH?

David Plachetzki: I've been at UNH for about 10 years. I’m an associate professor in the department of molecular, cellular, and biomedical sciences (MCBS) and also the coordinator of UNH’s genetics major.

COLSA: Can you give us an overview of your research?

David: My research focuses on understanding the genomic basis of novel traits in animals. We’re interested in how the genome evolves to facilitate the development of new traits, particularly sensory systems like vision, taste and hearing. For the past decade, my lab has studied animals like jellyfish and sponges, which allows us to identify the genetic precursors to traits like eyes or taste buds. By understanding the evolutionary origins of these senses, we can better comprehend their function in animals, including humans.

COLSA: What makes your research stand out?

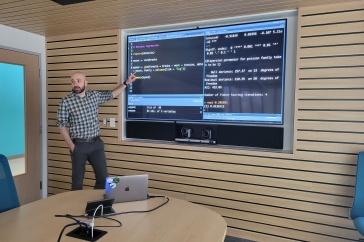

David: One thing that sets my lab apart is that we combine wet lab experimentation with computational biology. We’re multidisciplinary in that we use evolutionary genomics and molecular biology together to draw more powerful inferences about how traits evolved. Essentially, we're building the evolutionary 'instruction manual' for complex traits, so we can better understand their origins and function.

COLSA: What motivates you most in your work?

David: Starting new projects! There’s nothing better than that first day of a new research project with a bit of funding and endless possibilities. The excitement of diving into new territory, exploring new questions and having the freedom to pursue whatever direction the research takes us—that's what drives me.

COLSA: What are some of your long-term goals?

David: My ultimate goal is to develop a holistic view of gene evolution across all animal groups—what you might call a ‘Rosetta stone’ for animal genetics. This would allow us to trace the evolutionary history of every gene and every genetic function through time. It's ambitious, but the work we’ve done so far suggests it’s possible.

COLSA: Have there been any life-changing experiences that shaped your career?

David: SCUBA diving has definitely changed how I approach research. Taking advantage of UNH’s excellent SCUBA training program, I became a diver shortly after joining UNH and started conducting fieldwork on coral reefs in the Caribbean. This hands-on experience in natural environments has deepened my appreciation for the questions we ask about evolution, symbiosis and microbiomes.

COLSA: What do you enjoy doing outside of work?

David: When I’m not working, I play guitar, ski and spend time with my five-year-old daughter. Music has been a passion of mine for 40 years, but these days being a dad takes up most of my time—and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

COLSA: How would you like to be remembered?

David: Ultimately, I’d like to be remembered as a good dad. All the scientific work is great, but at the end of the day, it’s family that really matters.

COLSA: When did you first know you wanted to pursue a career in research or teaching?

David: It was during my senior year of college. Up until then, my professors kept telling me I should apply to grad school, but I didn’t really know what they meant. One day, I finally asked what it was all about, and once I started working in labs I realized that research was something I really enjoyed. I’ve been working in science ever since.

COLSA: Can you tell us about your experience pursuing your doctorate at the University of California, Santa Barbara?

David: My Ph.D. was pivotal in shaping my interest in evolutionary biology and genomics. One of the key studies I worked on there was the first to demonstrate that jellyfish could 'see' using vision genes and physiological pathways like those found in humans. This sparked my fascination with evolutionary processes and how they relate to complex traits like the senses. My interests in the evolution of complexity have morphed into new areas of research, but our basic approach is the same.

COLSA: Were there any key mentors who deeply influenced your work?

David: Definitely. My Ph.D. advisor Todd Oakley at UC Santa Barbara was a huge influence. He pushed me to think critically about biological questions and encouraged me to dive deeper into evolutionary biology. My postdoc advisors at UC Davis were also instrumental in treating me like a peer at one of the top institutions in the world, which gave me the confidence to pursue my own path.

COLSA: What was it like growing up in Michigan?

David: I grew up in the suburbs of Detroit, Michigan, and spent a lot of time around the Great Lakes, doing water-related activities like skiing in the winter. We spent summers in Traverse City, and I’ve always been close to nature, which probably helped foster my curiosity about biology. Go Lions!

COLSA: What do you consider to be a profound experience in your life?

David: One of the most profound experiences for me was SCUBA diving in the Galapagos in 2019. On my third dive of the day, we encountered a massive 20-foot-wide oceanic manta ray. It swam right next to us, and the entire moment was surreal. It wasn’t necessarily a 'happy' moment, but it was one of the most profound and humbling experiences of my life.

COLSA: If you could have dinner with any famous person, living or dead, who would it be?

David: I’d choose Stephen Jay Gould, the famous evolutionary biologist. He passed away before I got into the field, but I’m certain we would’ve had some lively debates about science. He was both inspiring but also wrong about a lot of things, and I think dinner with him would’ve been fascinating.