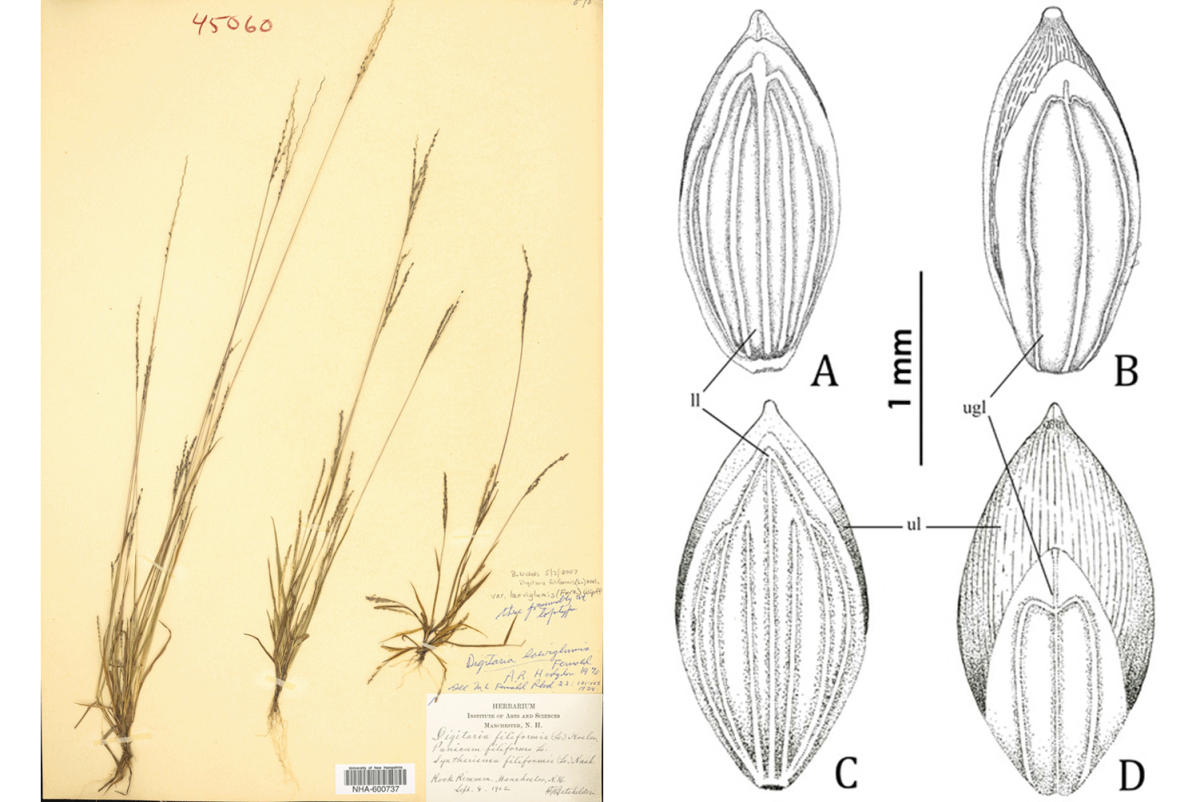

In 1901, several peculiar specimens of crabgrass were discovered on the rocky slopes of Rock Rimmon in Manchester, New Hampshire. Initially thought to belong to the species known as slender crabgrass (Digitaria filiformis), the slender, wiry plants with small, delicate spikelets were only known from this single location. But by 1931, they were last collected from the area, and the grass has not been observed since. Recently, UNH’s Albion R. Hodgdon Herbarium, which holds three of the last known remaining dried specimens of the grass, played a key role in identifying these plants as their own unique species, Digitaria laeviglumis, commonly known as smooth crabgrass.

“Using our three herbarium specimens, I worked with colleagues to genetically identify that this was, in fact, its own species, and that it has been extinct from New Hampshire probably soon after last documented in 1931,” said Erin Sigel ’03, Collections Manager for the Hodgdon Herbarium. “And I think over time, we’ll see more and more stories like this, about how our natural history collections contain ‘hidden species’ that we may have not even known existed and have now disappeared from our world.”

“Ethical plant collection will help reduce the likelihood that rare plant species go extinct in the future. Keeping this in mind, the importance of making new specimen collections for our public herbaria has never been greater given rapid environmental changes and loss of biodiversity.” ~ Bill Nichols, NH State Botanist and Senior Ecologist with the NH Natural Heritage Bureau and lead author of the study

The discovery of Digitaria laeviglumis involved collaboration among researchers at UNH, West Virginia University, Oregon, and in Mexico, as well as scientists from the NH Natural Heritage Bureau and was recently published about in an issue of Systematic Botany. This international team compared DNA sequences from specimens at UNH’s herbarium to those of related species, helping to confirm it’s globally extinct status. This marked the first documented plant extinction in New Hampshire (and the 65th documented plant extinction in the U.S.).

“Documenting the extinction of Digitaria laeviglumis has significant implications for biodiversity conservation,” said Sigel. “It highlights the vulnerability of endemic species, particularly those with very limited geographic ranges, and understanding the factors that led to the extinction of this grass can help inform conservation strategies for other at-risk species.”

“This case underscores the vital role herbaria play in preserving specimens and providing essential data for scientific research,” she added.

Bill Nichols, NH State Botanist and Senior Ecologist with the NH Natural Heritage Bureau and lead author of the study, noted that several factors contributed to the extinction of Digitaria laeviglumis, including increased recreation at Rock Rimmon over the last two centuries and over-collection by earlier botanists – 31 collections were made over a four-day span when last documented in 1931. Nichols and herbaria staff like Sigel emphasize that rare plant specimens should only be collected if there is a scientific need and if collecting them will not negatively impact plant populations.

“Ethical plant collection will help reduce the likelihood that rare plant species go extinct in the future,” said Nichols. “Keeping this in mind, the importance of making new specimen collections for our public herbaria has never been greater given rapid environmental changes and loss of biodiversity.”

This work is co-authored by William F. Nichols, Craig F. Barrett, Joseph K. Wipff, III, Jorge Gabriel Sánchez-Ken, Wesley M. Knapp, Erin M. Sigel, Lauren Kosslow, and Cameron Corbett.

To learn more about this research, read Molecular and Taxonomic Reevaluation of the Digitaria filiformis Complex (Poaceae), Including a Globally Extinct, Single-Site Endemic from New Hampshire, USA, and a New Species from Mexico, published in Systematic Botany.

Funding and support for this research came from the New Hampshire Conservation and Heritage License Plate Program, U.S. National Science Foundation Award, and the West Virginia Clinical and Translational Science Institute. Sequencing support came from the West Virginia University (WVU) Genomics Core Facility.

-

Written By:

Nicholas Gosling '06 | COLSA/NH Agricultural Experiment Station | nicholas.gosling@unh.edu