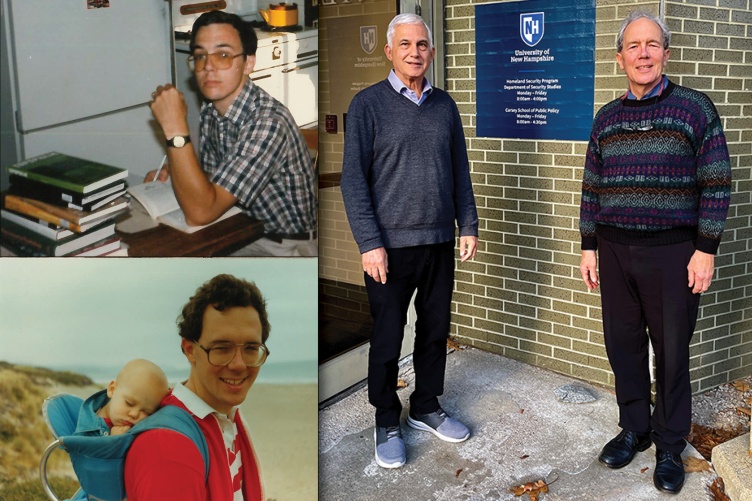

Top and bottom left: Chuck Hotchkiss as a young professor and father; on right, Michael Swack and Chuck Hotchkiss reunited at UNH

For Chuck Hotchkiss, the key to lasting social impact is ensuring that everyday people have a real share of the power in their communities.

“In organizing 101, they tell you that power is organized people and organized money,” he says. “Many times, marginalized populations—low-income populations, populations of color—have difficulty getting access to much-needed capital. [The Center for Impact Finance] and mission-driven lending institutions are working to fix that problem.”

“In organizing 101, they tell you that power is organized people and organized money,” he says. “Many times, marginalized populations—low-income populations, populations of color—have difficulty getting access to much-needed capital. CIF and mission-driven lending institutions are working to fix that problem.”

After forty-five years of teaching city planning and development, as well as practicing community organizing, Dr. Hotchkiss thought he was just about ready to retire. At the end of 2023, however, he was given the unexpected opportunity to helm Carsey’s CIF as its Interim Director. The chance to continue the great work of outgoing director Michael Swack was a welcome surprise. He accepted.

“I first met Michael back in 2006… I was doing community organizing with congregations and local labor unions and other membership-based groups,” he recalls. Later that year, the two became colleagues at Southern New Hampshire University. They worked together for another three years until Swack took a new position at Carsey, where he subsequently founded CIF. “I’ve always admired the work that he’s done, and this is a new thing [for me]!”

Dr. Hotchkiss learned early in life the importance of community development. He grew up outside of Youngstown, Ohio: a major hub in the steelmaking industry during the 19th and 20th century. During his childhood though, American steel lost its edge in the world market and Youngstown began a decades-long economic and social downturn from which it still has not fully recovered. In 1973, the year Dr. Hotchkiss graduated high school, U.S. steel production began a steady decline that would soon gut the industry.

“A lot of folks—especially those down near the bottom of the economic ladder—didn’t have a lot of options. People with a lot more options were leaving Youngstown for opportunities elsewhere,” he says, reflecting back. The city’s population today is less than half of what it was when Hotchkiss left for college. “It seemed like the folks who were left behind were, in many ways, trapped by circumstances of poverty, crime, and dysfunction.”

Dr. Hotchkiss acknowledges his good fortune in having a stable childhood and the chance to leave Ohio to attend Bates College. However, he wanted to focus his studies on the root causes of the issues that he had witnessed back home and hoped to discover ways that citizens might make their communities more resilient. After a wide-ranging, liberal arts education for undergrad, Dr. Hotchkiss enrolled in the City and Regional Planning PhD program at Cornell.

“I made the decision that I wanted to study city planning before I went to college,” he says. “I was interested in understanding how cities worked: I wanted to try and keep what had happened to Youngstown from happening in other places.”

For the master’s portion of his degree, Dr. Hotchkiss examined the role of entrepreneurship in cities and whether it could be quantified: an interest that perfectly resonates with the work at CIF. It was also at Cornell that Dr. Hotchkiss got his first taste of teaching, which ignited a lifelong passion for working with students. In 1985, he moved to southern California with his wife, who had accepted a one-year internship in Los Angeles. Twenty-five miles east of the city, another unexpected career opportunity presented itself.

“There was a one-year sabbatical replacement position available at [Cal Poly] Pomona in the Urban and Regional Planning program,” Dr. Hotchkiss says, smiling. He got the temporary job, only to learn the school wanted to recategorize it as tenure-track because of a last-minute vacancy. “[I said] Doesn’t matter to me, I'm only going to be here a year! Call it whatever helps you administratively... And then I stayed for fifteen years.”

Dr. Hotchkiss thrived in the diverse academic community of Pomona, where many of his students were people of color, economically disadvantaged, and from immigrant families: exactly the kind of marginalized populations who were hit hardest by the collapse of the Youngstown economy. Cal Poly’s program saw itself as the scrappy underdog to better-funded ones at USC and UCLA, but it was Pomona that produced more graduates who would go on to work in municipal government.

Over his decade and a half at Cal Poly, Dr. Hotchkiss completed his doctorate and helped to teach an entire generation of city planners, instilling the value of community participation in decision-making. In spite of the countless hands-on development projects he had done with his students, he began to bump up against the limits of how much good one can do through academia and local planning.

“The capacity to address social justice issues as a local planner is pretty constrained,” he says. Dr. Hotchkiss wanted to do more to connect people to the power structures that governed their lives. “I wanted to have the flexibility to act on my concerns about community development and social justice more directly, which is why I left and went into community organizing.”

In 2000, Dr. Hotchkiss moved back across the country to Durham, NH—where he and his wife could be closer to family—and threw himself into community organizing. After two years of building relationships across different community groups and identifying issues of shared concern, he helped to found Granite State Organizing Project in 2002. The non-profit works to promote economic and social justice by helping communities build power through collective understanding and action. Dr. Hotchkiss sees these connections as the only way for those who have been historically excluded to “get a seat at the table.”

One of GSOP’s earliest public actions brought together residents of central Manchester who wanted better standards for workers on a nearby construction project. Dr. Hotchkiss recalls that most local politicians skipped out, only for 600 of their constituents to show up and make their voices heard. As part of the meeting, organizers asked all the community members to turn around, find someone they didn’t know, and speak together for a time.

“Members of the local laborers union were seated directly behind the Sisters of Mercy, so there was a moment where these nuns and these laborers—in their leather vests, tattoos, and the whole thing—they have this conversation!” he says, reveling in the memory. “What they found was, they’re all concerned about the same things. Even though these couldn’t have been two more different-looking groups, they were there for the same basic reasons. That had a really powerful effect on me.”

Since settling in New Hampshire, Dr. Hotchkiss has kept his focus mostly on organizing, but has also jumped back in and out of higher ed, jokingly calling himself “a recovering academic.” During this time, he taught at SNHU for four years, then served two roles at Wentworth Institute of Technology: first as an associate provost and later as dean of the university’s College of Architecture, Design, and Construction Management. During this time, Dr. Hotchkiss integrated his passions for teaching and social justice by incorporating community development operations into learning experiences for students, including major projects in Boston, Roxbury, and Dorchester.

Dr. Hotchkiss knows he has big shoes to fill, stepping in for the director who also founded the Center for Impact Finance. He hopes to use his tenure as interim director to keep the center’s staff in the best position to succeed while laying the groundwork for his eventual successor.

“The center has grown considerably in the last couple years in its potential to do more good work,” he says. “My purpose here is simply to come in and keep the trains rolling.”

“The center has grown considerably in the last couple years in its potential to do more good work,” he says. “My purpose here is simply to come in and keep the trains rolling.”

To take it back to organizing 101: power comes from organized people and organized money. Dr. Hotchkiss’s career is a testament to the good that can be done in bringing residents together and participating in the shaping of their communities. It seems fitting that he now has the opportunity to lead CIF in its mission to ensure those people’s community development efforts have the funding they need.

“The folks who are involved with the center, their passion is rooted in the same kind of concern that I've got for the populations that are getting left out,” he says. “I simply [hope] to create the conditions where the staff can continue to do the great work they’re doing.”

Reported by Benjamin Scott Savard, ‘23G