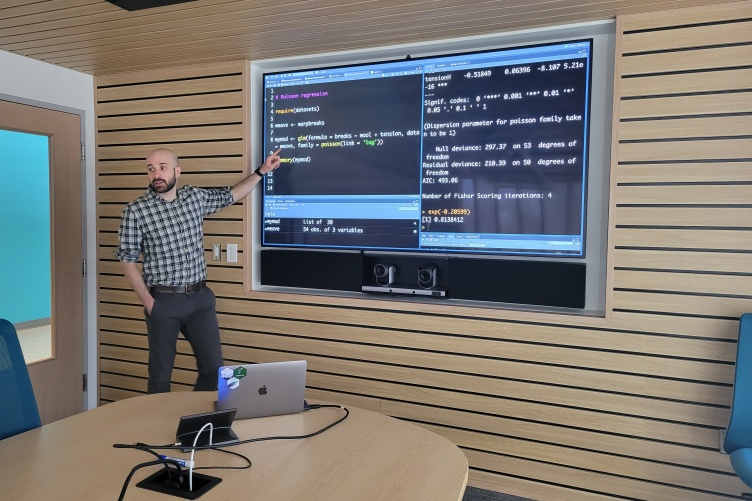

Assistant Professor Easton White demystifies quantitative skill building for graduate students.

Although developments in biology over the past 20 years increasingly require researchers to use advanced quantitative skills such as mathematics, statistics and programming, biology students continue to often reach graduate school without the needed training in those areas.

In a new paper in Bioscience, researchers, including Easton White, assistant professor and quantitative ecologist in the department of biological sciences, argue that focusing on building self-confidence and self-efficacy among graduate students with respect to quantitative skill building may improve both educational outcomes and professional success.

The field of biology is changing. Over the past two decades, an increase in available data combined with expectations that biologists use data to predict future conditions and assess risks, have led to an accompanying increase in the need for researchers with advanced quantitative skills. As further evidence, the researchers note that these new competencies are being sought by companies hiring for entry-level positions.

“We think about biology and math or statistics as separate, distant fields, but we need statistics, programming, mathematics — all those tools,” says White. “You can't just have a degree in biology anymore. If you say to an employer, ‘I have these programing skills’ that's what's going to get you a job. We want to demystify those areas so students understand that these are skills that biologists not only need but can learn, too.”

Examining the problem strictly at the graduate level, the researchers conclude that when students enter graduate school without quantitative skills, the main obstacle to obtaining them is a lack of self-confidence — a person’s belief in their ability to influence outcomes in their life — and self-efficacy — a belief in one’s ability to perform a specific task is a given setting to attain a goal — accumulated for a variety of reasons throughout the course of their education.

“We think about biology and math or statistics as separate, distant fields, but we need statistics, programming, mathematics — all those tools. We want to demystify those areas so students understand that these are skills that biologists not only need but can learn, too.”

Self-efficacy is an important self-belief to cultivate in students,” says Melissa Aikens, associate professor of biology and discipline-based education researcher, who was not involved in the published article but works closely with White. “If students don't think they can successfully complete a task, they may put in less effort on the task, and they are less likely to persist when they encounter difficulties. So when we think about teaching quantitative skills to graduate students, we really need to be thinking about how we can do that in a way that fosters the development of their self-efficacy.”

The lack of confidence some graduate students experience is intensified by a profound aversion to failure common among graduate students. The researchers, however, argue failure should be socialized as productive and a normal part of acquiring new skills.

At UNH, White has taken steps to address advanced quantitative training for graduate students, including introducing a graduate-level BIOL 806: Data Science with R for the Life Sciences in 2021. Even with room for up to 50 students, not just from COLSA but from across graduate programs, White says the demand for the class has consistently exceeded the available spots.

“One exercise I love doing is ‘Fail Fridays’ where everyone can submit the bad graphs they made that week,” says White, who also hosts short hackathons that bring students together in a relaxed, informal context to work on one problem together. “There is a lot of teaching about how to fail productively.”

But when the researchers turned their attention to exploring proven pedagogical approaches that address the challenges of self-confidence and self-efficacy with respect to quantitative training, they didn’t find much pertaining to graduate education.

There are very few published studies addressing quantitative education at the graduate level, and most studies that do exist evaluate methods based only on skill building, not on their impact on enhancing quantitative self-efficacy — leading the team to conclude that more research on training strategies that effectively increase quantitative self-efficacy and, in turn, benefit both students and the broader field of biology, is needed.

The team’s study, and the research that may result, also has important relevance for groups underrepresented in the STEM fields, including women, persons historically excluded because of ethnicity or race, LGBTQ+, and those with disabilities, all of whom have faced unique barriers that impact self-confidence such as low expectations and stereotypes related to gender and race.

White was joined in this work by Kim Cuddington (lead author), Karen C. Abbott, Frederick R. Adler, Mehmet Aydeniz, Rene Dale, Louis J. Gross, Alan Hastings, Elizabeth A. Hobson, Vadim Karatayev, Alexander Killion, Aasakiran Madamanchi, Michelle L. Marraffini, Audrey McCombs, Widodo Samyono, Shin-Han Shiu and Karen H. Watanabe.

-

Written By:

Sarah Schaier | College of Life Sciences and Agriculture