A Trio of Fungi Finds

These three easily identified gourmet species can be found in abundance in the fall.

- The black trumpet (Craterellus fallax) is a gill-less mushroom often found in great quantities in forested areas, growing directly out of the leaf litter. Look for moist woodlands with lots of oak and hemlock.

- Hen-of-the-woods, also known as maitake (Grifola frondosa) is typically found in mid-fall around the base of mature oak trees and has pores rather than gills on its underside. Occasionally upwards of 40 pounds of this mushroom can be found growing from a single tree.

- Chicken of the woods (Laetiporus sulphureus) is bright orange and yellow and also has pores rather than gills on the underside of each bracket. It should only be consumed when growing from hardwoods.

Say what you will about 2021, but the year is shaping up to be phenomenal for mushrooms. Take a walk outside and you are likely to see a variety of sometimes colorful, often crazy-shaped fungi, poking out from piles of leaves, attached to trees, and even bursting out of sidewalk cracks. For the aspiring amateur mycologist or forager, the sheer abundance and diversity can be overwhelming. A good mushroom guide and a healthy sense of caution are a fine place to start — but there’s just no substitute for hands-on experience.

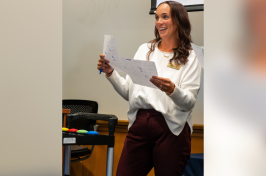

Just ask the students in the College of Life Sciences and Agriculture’s “New England Mushrooms” class who have been spending time this fall in the field and the lab learning how to identify, cultivate and prepare these teeming toadstools. The course, which is taught by Chris Neefus, professor of biology and director of the UNH Hodgdon Herbarium, attracts undergraduates, graduate students and the occasional faculty member and town resident.

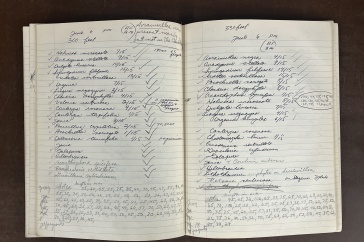

Driven by abundant rainfall during the past summer, mushrooms, which are 80-90% water, are emerging in force. In September alone, students in the class collected 108 species, mostly from College Woods. Neefus expects that number to grow as the season progresses.

“There are about 10,000 described species of mushrooms in North America, about 6,000 east of the Rocky Mountains,” says Neefus. “About 250 species are known to be edible. Certainly many more that have not been discovered, studied and named.”

When Neefus's students aren’t collecting mushrooms, they can be found in the laboratory carefully identifying specimens based on microscopic traits such as spore shape and running DNA analyses on some of the trickier specimens. Neefus recently added a cultivation element to the course. Students are growing their own mushroom cultures and will eventually produce their own gourmet varieties, such as shiitakes (Lentinula edodes), oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus), and lion’s mane (Hericium erinaceus).

When students stumble across large quantities of edible mushrooms, they are often eager to taste their finds. Under Neefus’s guidance that includes safe preparation and consumption practices, the class has also begun to explore the many culinary uses of edible varieties. Ever heard of mushroom jerky? How about candied jelly-tooth? These mycological delicacies are tastier than they might sound and limited only by creativity.

No one knows this better than Evan Mallett, chef-owner of Black Trumpet Bistro in Portsmouth, which he named after the black trumpet (Craterellus fallax), one of his favorite gourmet wild mushrooms. Mallett regularly forages and serves his own wild mushrooms in the forms of ice cream, mushroom-infused pastas, fresh pickles and more. He describes his restaurant as a “gastronomic laboratory.”

“I do everything I can with the mushrooms that are available,” says Mallett. “A wild food, be it plant, fungus or animal, has seasons that are very specific and often very short. These foods are good for us and at their peak nutrition when they are available and abundant.”

Back in Neefus’s classroom, wild mushroom dishes are certainly a hit. “The culinary aspect of the class is really enjoyable,” says Chloe Tardanico ‘22, an environmental conservation and sustainability major. “Not every class gives you the opportunity to go foraging and then learn how to prepare a meal from the woods.”

Tardanico also values the class as a welcome break from a more typical classroom routine. “Rather than learning only from lectures, we’re out in the field, asking questions, and analyzing our surroundings,” she says. “Everyone is really dedicated and interested in the class, so we all work together and learn from each other, which is exciting and fun.”

For anyone interested in the world of wild edible mushrooms, fall is a great time learn. If enrolling in Neefus’s mushroom course isn’t an option, the easiest — and safest — way to begin mushroom hunting is to find an experienced mushroom forager and join them for a walk. A field guide with high-quality color photos is also a must-have. In general, beginners are advised to avoid consuming mushrooms with gills, as many of the most toxic species, such as the destroying angel (Amanita bisporigera), death cap (Amanita phalloides), and funeral bell (Galerina marginata), are gilled mushrooms.

For Neefus, the sometimes daunting world of mushroom identification is what makes it fun. “We now know very closely related species can look very different from each other, and two mushrooms that look very similar can be only distantly related,” says Neefus. “I love the opportunity mushrooms provide for surprise and discovery.”

Note: Please do not collect and consume mushrooms based only on the information in this article. Always consult a reliable field guide and a trusted mushroom hunter before consuming any wild mushroom.

-

Written By:

Benjamin Borgmann-Winter | UNH College of Life Sciences and Agriculture