Plastic trash accumulates in the Chicago River, Illinois. Photo by Tim Hoellein, University of Loyola, Chicago.

As rivers flow to the ocean, they carry with them more than just fresh water — plastic litter of all shapes and sizes is washed or blown into streams and can harm animals and pollute drinking water along the way. Scientists are now trying to figure out just how much of that plastic stays within the rivers instead of washing out to sea.

A team of UNH researchers has received a $429,900 grant from the National Science Foundation’s Hydrologic Sciences Program to estimate the amount of plastic accumulating in rivers near three major metropolitan regions: Boston, Massachusetts; Chicago, Illinois; and Toronto, Ontario. The data gleaned from this project will help water resource managers identify hot spots for plastic pollution in order to prioritize clean-up locations and could help them determine how much plastic is building up in streams and rivers and whether or not drinking water sources are being impacted.

The research team is led by Wilfred Wollheim, UNH associate professor in the Department of Natural Resources and the Environment and in the Earth Systems Research Center (ESRC).

|

| Not all plastic washes out to sea. here, plastic litter accumulates in the Chicago River, Illinois. Tim Hoellein, University of Loyola, Chicago. |

Richard Lammers, a research assistant professor in the ESRC, Shan Zuidema, an ESRC research scientist, and Wollheim will collaborate with researchers from the Loyola University of Chicago and the University of Toronto on the project, with a total grant award of $850,000.

“So much of our plastic is unaccounted for, even after considering recycling, garbage and what ends up in our oceans,” Wollheim says. “So where is the rest of that plastic? Rivers are not simply pipes that deliver plastic to the ocean. As it moves downstream, it may settle, break into pieces or interact with aquatic life. We suspect a lot of that unaccounted plastic is building up in surface waters like rivers, but we just don’t know how much of it is accumulating there.”

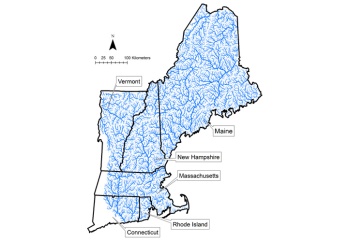

The research team will take a novel approach by combining computer models and field measurements to estimate how much plastic accumulates within the rivers, how long it stays there and how storms affect its movement towards the sea. The UNH researchers will sample rivers within Massachusetts’ Ipswich River Watershed, which empties into Plum Island Sound, to find and characterize plastic floating on the water surface, suspended in the water column and stored in the sediments or on the riverbanks. Scientists from the two collaborating universities will sample their own metro area rivers. All combined, these data will provide a bigger picture of plastic pollution within temperate climates.

Wollheim says the findings from this research could help resource managers figure out strategies for preventing plastic from entering rivers and develop more effective approaches for cleaning up the pollution. He’s hopeful the research will also contribute to the larger picture of plastic transport and fate within aquatic systems of the Northeast, as well as help people think about the impact of their own plastic waste.

The Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space (EOS) is UNH's largest research enterprise, comprising six centers with a focus on interdisciplinary, high-impact research on Earth and climate systems, space science, the marine environment, seafloor mapping and environmental acoustics. With more than $60 million in external funding secured annually, EOS fosters an intellectual and scientific environment that advances visionary scholarship and leadership in world-class research and graduate education.

-

Written By:

Rebecca Irelan | Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space | rebecca.irelan@unh.edu | 603-862-0990