CCOM researchers Jaya Roperez and Rochelle Wigley spent a month aboard the DSSV Pressure Drop to map fascinating features on the South Pacific seafloor.

When scientists discovered the world’s deepest-known shipwreck and explored the trenches in the lowest points of the ocean this spring, they relied on detailed seafloor maps created by UNH researchers to navigate around safely.

Jaya Roperez, a graduate student and marine surveyor at the UNH Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping, and Rochelle Wigley, the project director for the Nippon Foundation / General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO) Training Program, spent a month aboard a ship near Micronesia and the Philippines, where they mapped the seafloor to help scientists explore three fascinating undersea features: Challenger Deep, the deepest point on Earth and part of the Mariana Trench; the Philippine Trench, the third-deepest point on Earth; and the previously unconfirmed wreckage of the USS Johnston, a WWII battleship from the Battle Off Samar that is the deepest-known wreck at about 6,400 meters — almost 4 miles — below the ocean surface.

Rochelle Wigley and Jaya Roperez worked long hours mapping the seafloor in the south pacific this spring.

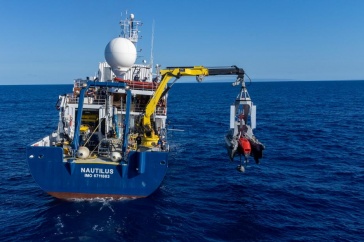

The expedition took place aboard the DSSV Pressure Drop, a vessel owned by deep sea explorer Victor Vescovo. The ship carried with it a submersible vessel, the DSV Limiting Factor, capable of diving to 11,000 meters — almost 7 miles down — with a crew of two in its tiny cabin. At least 30 scientists and crew members took part in the overall expedition.

For Wigley, it was a golden opportunity to go to sea for the first time in almost a dozen years — and at a time when many other ocean scientists were hampered by COVID-19 travel restrictions. She and Roperez worked long overnight shifts, using cutting-edge multibeam echosounder technology to visually capture the seafloor features and create extremely detailed maps for the crew that would descend to the depths the following day.

The Challenger Deep and Philippine trench had been previously mapped by the DSSV Pressure Drop, but the team wanted to confirm the deepest points, particularly in the Western Pool region for the Challenger deep, where they wanted to land the submersible vessel.

While traveling between each dive site, Roperez and Wigley also surveyed during transits and collected additional data to help create charts of previously unmapped regions of the Pacific Ocean seafloor. To date, less than 20 percent of the world’s oceans have been mapped. The Nippon Foundation - GEBCO Seabed 2030 Project, with its ambitious goal of mapping the entire ocean floor by the year 2030, provided the financial support for Wigley and Roperez, through the alumni-led Map the Gaps Non-profit, to participate in this expedition, and the Project will receive the data they collected.

“We didn’t want to waste the transits, because each little bit of data is like a puzzle piece that adds to the overall picture,” Wigley says. “It was fascinating to be there when brand new data were collected, looking at all the changes across the Pacific Ocean like seamounts and incredibly deep trenches — the seafloor was incredibly variable. It was also really great to work with the team and the cutting edge technology onboard and to better understand the data collection processes.”

For Roperez, this was her third mapping expedition aboard the Pressure Drop. In March 2019, she took part in a 24-day transit mapping trip from Capetown, South Africa, to Fremantle, Australia, during which they surveyed the deepest point in the Indian Ocean. Later that year, Roperez helped out with an 11-day transit mapping trip from Newfoundland, Canada, to Svalbard, Norway, to survey the deepest point in the Arctic Ocean.

What made this recent expedition unique and even more exciting, she says, was the discovery the USS Johnston, which scientists had previously suspected to be in that region but had not confirmed its presence.

“I initially told Victor (Vescovo) that it would be very hard to see the shipwreck just with the multibeam echosounder data alone, but that perhaps we could find clues from the backscatter, in my mind considering the wreck was in pieces on a soft-material seabed,” Roperez recalls. “We ran over the suspected location multiple times in different directions and some survey lines picked it up — lucky us!” Vescovo then used the submersible vessel to dive on the shipwreck and found the bow, which confirmed that it was indeed the USS Johnston from the WWII Battle Off Samar in the Philippines, and was thus classified as the deepest-known wreck in the world.

“I’m really thankful to CCOM, Map the Gaps and Seabed 2030 for giving me these wonderful opportunities,” Roperez says. “I consider myself so lucky to be able to map the deepest point on Earth and a previously undiscovered shipwreck, to see how they actually do the manned submersible dives and to be part of something great and worth reminiscing about when I’m older.”

The Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space (EOS) is UNH's largest research enterprise, comprising six center with a focus on interdisciplinary, high-impact research on Earth and climate systems, space science, the marine environment, seafloor mapping, and environmental acoustics. With more than $60 million in external funding secured annually, EOS fosters an intellectual and scientific environment that advances visionary scholarship and leadership in world-class research and graduate education.

-

Written By:

Rebecca Irelan | Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space | rebecca.irelan@unh.edu | 603-862-0990