If you were to investigate ways to support forest health, where would you look? The trees? Animals? Soil?

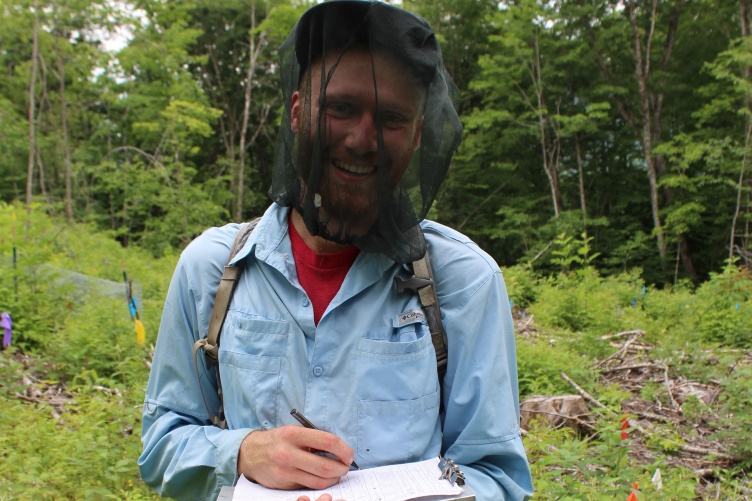

For Ben Borgmann-Winter, a wildlife ecology masters student in UNH’s natural resources and the environment program, the answer is fungi. His research builds on the work of assistant professor of natural resources Rebecca Rowe to investigate how animals impact forest regeneration. Specifically, he studies mycorrhizal fungi, which are a type of fungi that form symbiotic relationships with trees. In this trade-off, fungi give water and nutrients to trees in exchange for sugar.

Basically, more mycorrhizal fungi translates to healthier trees and, ultimately, healthier forests.

So how do these fungi find their trees? While it is generally understood that mycorrhizal fungi disperse via wind, recent research in Rowe’s lab has found that small mammals such as chipmunks can play an important role in spreading fungi, too.

The focus of Borgmann-Winter’s studies is on these small mammals as consumers and dispersers of mycorrhizal fungi.

“Ben’s research not only provides important basic insights into a key set of ecosystem functions, it will also help understand how forest practices can be improved to better protect and enhance the small mammal-mycorrhizal-tree seedling feedback,” says Mark Ducey, natural resources department chair.

This summer, with the help of a Summer Teaching Assistant Fellowship (STAF), an award given by the UNH graduate school to students who have served as teaching assistants and have performed exceptionally well both as TAs and students, Borgmann-Winter has been performing his field work at Dartmouth University’s Second College Grant in northern New Hampshire.

“My work, like the work of most folks studying ecology, is the study of systems and interconnectednesss,” says Borgmann-Winter. “I think there is an unfortunate lack of appreciation in our country for the interconnectedness of entire systems—be those human systems, natural systems, or some hybrid of the two. In this very moment as a nation, many of us are grappling with the fact that what we do affects others, who in turn impact other individuals that we will never meet. We are all part of a system, but it is hard to fathom just how interconnected we are.”

Borgmann-Winter’s research provides just the opportunity to consider interconnectedness right here in New Hampshire. And while the specifics of his research are not exactly human, he finds stark parallels and insights to our current moment:

“The pandemic has laid bare the fact that we, as a society, struggle to think about systems and the downstream impacts of actions. I think ecologists have a special responsibility to continue to uncover and share the amazing interconnectedness of our world so that we can become more accustomed to systems thinking in general. We face a global health crisis, we face a climate crisis, we face a race crisis (all of which are connected, by the way). Just solutions to these crises will require systems thinking at an immense scale.”

-

Written By:

Lily Greenberg '21G | Grad School