MILT PRIGGEE / CAGLE CARTOONS

The pipe bomb arrived at CNN’s New York City office on an October morning in 2018. The improvised device, delivered by courier, was one of 13 sent to targets across the country — all Democratic politicians, high-end donors and outspoken critics of President Trump. Michael D’Antonio ’77 wasn’t in the building when the package was discovered, but the CNN contributor and writer, who provides regular critical analysis of the president and his policies, was likely among those the bomber hoped to reach. And while none of the bombs, including the one sent to CNN, were detonated, it wouldn’t be the last time D’Antonio would face threats for his political commentary.

In the past few years, D’Antonio, author of “Never Enough,” a 2015 biography on Trump, has received several menacing phone calls and emails. He’s also been the subject of the president’s tweets.

“It’s a very strange thing to get emails that say, ‘I’m going to come rip off your skin and dismember you, and your family isn’t safe either,’ ” says D’Antonio.

A journalist for 40 years, D’Antonio is accustomed to criticism and name-calling, but never before has he witnessed such vitriol.

“It’s upsetting to have people express such hatred and creative violent imagery about you,” says D’Anotonio.

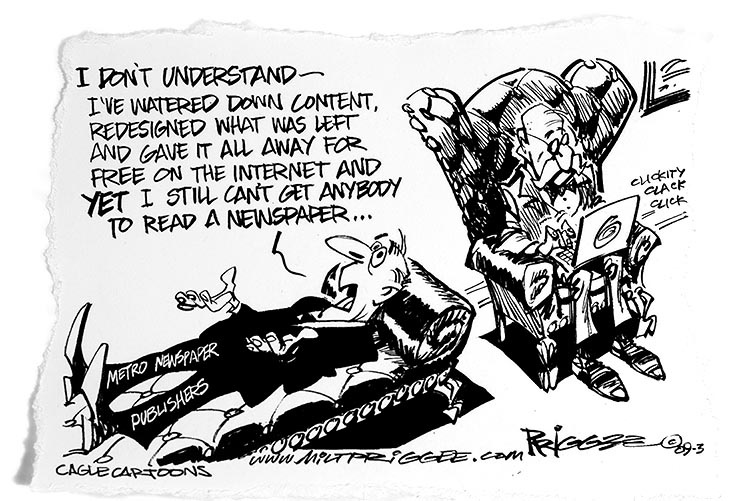

With the president’s near-daily tweets about fake news and referring to the media as the “enemy of the people,” public confidence in journalists has eroded to record lows. Amid the media mistrust, the Columbia Journalism Review reports that the news business faced its worst job losses in a decade, with more than 3,000 people laid off or offered buyouts in the first five months of 2019. Newspapers, according to 24/7 Wall St., have been the hardest hit, with more than 2,000 closing since 2004.

“Carving out a life in journalism is more difficult than it ever has been in my lifetime,” says D’Antonio.

With shrinking newsrooms, uncertain futures and a profession under siege by the president and his supporters, what motivates journalists to continue working in the field? How do they navigate the ever-changing media landscape in an era of fake news and fewer opportunities?

The answers are as varied as the jobs that scores of UNH journalism graduates hold across the country. From CNN to online start-ups and newspapers big and small, reporters and editors admit competing against free internet news and social media is daunting.

But as digital news sites grow more popular, so, too, do opportunities, says UNH Journalism Program Director Tom Haines.

FEATURES, INC.

“This generation is creating a new kind of journalism,” says Haines, who began teaching at UNH in 2011 after working in newsrooms for 16 years. “They may not be headed to a brick-and-mortar style newsroom, but they are incredibly optimistic about creating journalism out of the technology that is available.”

And regardless of whether they are working at a newspaper or an online start-up, veteran and novice journalists alike believe their role in informing the public has never been more crucial.

A New Urgency

Kevin Sullivan ’81, a Pulitzer Prize-winning senior correspondent who covers national and international news for the Washington Post, says the current presidential administration has created an urgency about the news.

“People are involved in public life in a way they never have been before, motivated by their love or hate of [the president],” Sullivan says. “The media has been caught in the middle of it, and it’s kind of fascinating. What we do has never felt more important or urgent.”

With a relentless stream of national news — including historic coverage of impeachment inquiries — large papers like the Post, New York Times and Wall Street Journal are flourishing, with increased subscriptions and healthy newsroom staffs. Yet smaller local papers continue to struggle, losing circulation, ad revenue and reporters.

According to the Pew Research Center, the number of newspaper employees dropped by 47 percent between 2008 and 2018, from about 71,000 workers to 38,000.

“The true crisis is at the local level, with papers shutting down,” says Nick Stoico ’15, who began working at New Hampshire’s Concord Monitor soon after he graduated. “Without newspapers, there’s a lack of accountability, and we need to find a way to continue to tell the local stories about the planning board and town council. It’s an important part of civic life.”

During his four years at the Monitor, Stoico saw the newsroom staff dwindle. Though he improved his reporting, writing and editing skills at the Pulitzer-Prize winning newspaper, Stoico had concerns about his future.

This summer, he left the Monitor to pursue a master’s in journalism at Northeastern University to learn more about new media and digital reporting.

“I felt like I needed to add a little more to my toolbox,” says Stoico. “I plan to have my full career in this business, and to make that happen I need to know more than just reporting and writing at a small newspaper.”

Like Stoico, Breanna Edelstein ’14 considers herself fortunate to have landed a job at a medium-sized daily newspaper not long after graduating. Edelstein was hired at The Eagle-Tribune in North Andover, Massachusetts, where she has worked for the past 4½ years.

During that time, there have been no layoffs in the Pulitzer-Prize winning paper’s editorial department. The Eagle-Tribune, Edelstein says, also encourages its reporters to pursue investigative stories and gives them the time and resources to report on the longer narratives.

This spring, Edelstein broke a story about a North Andover High School policy that required a sexual assault victim to sign a contract limiting her movement in the same building as the classmate who had been arrested and placed on probation for attacking her.

Edelstein also learned the girl was not alone. Three other victims said they were assaulted by the same student. And it was discovered that more cases of sexual assault were handled with contracts. Due to Edelstein’s reporting, the school changed its policy, which had threatened to discipline sexual assault victims if they did not avoid contact with their assailants.

“It felt great to make a difference, to change this school’s policy, to know these contracts aren’t used anymore,” Edelstein says. “It may sound cliché, but that’s why we do this job.”

Despite the foreboding forecasts about daily newspapers, Edelstein hopes to continue telling stories that matter.

“I’m a print girl and I’d love to stay right here in this field,” she says. “The internet is so big; stories can get lost there. I think there is still value in the front page of a newspaper.”

Still, Edelstein knows several friends who have left print journalism for more lucrative and stable careers. One colleague recently sent her a story that indicated that for every journalist who stays in the business, there are six who shift gears and head for careers in public relations.

“I’ve been tempted to go into P.R., but I decided I just couldn’t do it,” she says.

Culture Shift

A journalist for nearly 50 years, John Christie ’70 has witnessed everything from the 1980s newspaper boom to the industry’s downward spiral following the creation of the internet and the rise of social media. “I was grateful to work in this business during its heyday when newspapers were financially successful, and for the most part, people believed what we wrote,” he says.

Christie, who began his career as a reporter for The Beverly Times in Beverly, Massachusetts, has worked for newspapers in Florida and Maine, where he has held multiple editing jobs and also served as publisher. “I feel bad for reporters today because there isn’t much they can do in newspapers to advance their careers,” he says. “There are very few layers of editors left, so there aren’t a lot of ways to move up and earn decent money.”

Frustrated with newsroom cuts and declining circulation, in 2009 Christie and journalist Naomi Schalit founded the Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting. The center’s nonprofit online news service, Pine Tree Watch, focuses on in-depth and investigative journalism. Like National Public Radio, it relies on donations and foundation money.

“When newspapers cut staff, reporters who do long-term work are the first to go,” Christie says. “In-depth stories that take effort and time to research and write don’t get done. Democracy depends on those types of stories, and that’s why we founded Pine Tree Watch.”

Now a consulting editor for Pine Tree Watch and a contributor to WBUR public radio, Christie isn’t optimistic about the future of newspapers. With Google and Facebook gobbling up 60 percent of U.S. online ads, there is little left for local papers trying to earn dollars digitally. In the next five to 10 years, Christie predicts hundreds more newspapers will go out of business. Some may become online-only outlets; others will die completely.

Hoping to prolong their careers, several other UNH journalists have turned to nontraditional sites that publish solely online.

At The Athletic, an ad-free, subscription-based sports news site, the culture is “drastically different from newspapers,” says Chad Graff ’12. Graff began working at the company in January 2018, covering the Minnesota Vikings.

“They’ve been very competitive with salaries and very aggressive in hiring people,” Graff says. “It’s been a culture shift working for a company that is constantly welcoming people every single month.”

Graff’s outlook on sports journalism wasn’t always so optimistic. In high school and while he studied journalism at UNH, Graff covered local sports at the Union Leader in Manchester, New Hampshire.

“From 2008 to 2013, I saw the unfortunate reality of the business,” Graff recalls. “I saw the newsroom shrink. I saw wages cut. I saw furloughs.”

The paper’s veteran reporters often asked Graff, “You sure this is what you want to do?”

As Graff and a UNH classmate sought sportswriting internships, they grew accustomed to receiving rejection letters.

“We sent out 30 applications,” Graff says. “And every time we’d get a no, we’d hang it on the wall of The New Hampshire newsroom, competing to see how many we each could get.”

By the end of the competition, 50 rejection letters covered the wall. Luckily, Graff ended up with an internship at the Philadelphia Inquirer, which helped him get a job at the St. Paul Pioneer Press covering professional hockey.

“It was a great job and they sent me all over the country, but over my five years there, I saw the same thing I’d seen at the Union Leader: downsizing, buyouts, budget constraints.”

Created in 2016, The Athletic covers professional and college sports, offering longer, more in-depth stories “that go beyond the box scores.” The company now has 300 employees and more than a half-million subscribers. Yet, the viability of online subscription news sites remains uncertain. The Athletic, which has relied on private investments, has yet to make a profit. Still, Graff is hopeful that the company will continue to grow.

“After so many years of seeing newspaper circulation down and hearing that no one will pay for stories online, it’s been rewarding to see our subscriptions grow and that more than 600,000 people will pay for quality content,” Graff says. “So, that leaves me encouraged.”

Marcus Weisgerber’s journalism career took a different trajectory when he left daily newspapers for a trade magazine called Inside the Air Force in 2006. Since then, Weisgerber ’04 has reported on military and national security issues. He’s currently the global business editor for Defense One, an online news site covering national security and defense.

“They’ve done a masterful job of figuring out how to make money as a media company and not just on traditional advertising,” explains Weisgerber. “They also make a lot of money on editorial-driven events.”

As part of his job, Weisgerber is responsible for inviting and interviewing high-level military and national security leaders to speak at public venues. He creates podcasts, provides radio and television commentary and revels in covering historic military milestones.

“I always tell people I have a front seat at history being made,” says Weisgerber. “I’ve driven across Kabul with the Afghanistan Ministry of Defense and the Secretary of Defense. It’s a rush wearing body armor and being in an armed car racing through the streets in a motorcade.”

Like many of his colleagues who rely on national government sources, Weisgerber’s job has gotten tougher during the Trump presidency. Military and Pentagon employees are reluctant to speak, fearing a reprisal from the White House.

“Everyone is afraid to talk on the record right now,” Weisgerber says.

In this turbulent climate, Weisgerber believes reporting on military and Pentagon funding has never been more vital.

“I cover budget and acquisition issues and procurement of equipment,” he explains. “People’s lives are literally at stake, depending on where the Pentagon spends the money and the type of equipment they’re buying and who they’re buying it from. Everything I am writing about involves life or death.”

Blue Skies and Sunshine Ahead?

Like other UNH alumni, the Washington Post’s Sullivan has weathered turbulent times. In the years leading up to and following the 2008 recession, the Post, one of the most respected news organizations in the country, was not immune to layoffs, buyouts and financial woes. When Sullivan returned from working in the Post’s London bureau in 2009, dismal morale and uncertainty plagued the storied paper, which had won scores of Pulitzer Prizes and had broken stories on the Watergate scandal and the Pentagon papers.

“It was a tough time to be here,” recalls Sullivan, a 28-year veteran at the Post. “Every single day, we had these ‘cakings,’ ceremonies for someone else who was leaving. It was just the reality of the business, and it was getting worse and worse.” The Graham family, who had owned Washington’s leading newspaper for four generations, struggled to support the paper’s financial losses. In 2013, the family sold the Post to Amazon.com founder and CEO Jeffrey Bezos.

“The Washington Post was in the Grahams’ blood and to arrange the sale with Bezos was a selfless thing,” says Sullivan. “It was to give the paper a chance.”

Since Bezos bought the paper, 250 people have been hired in the newsroom and circulation and online subscriptions “are through the roof,” Sullivan says. “It’s not all blue skies and sunshine, but it’s pretty close. Journalism has never been better here.”

The Post, often a target of Trump’s tweets, has been frequently accused by the president of fabricating lies and printing fake news. During his election campaign, the president revoked the paper’s press credentials at his rallies. But the president’s animosity toward the Post has done little to change the way its reporters and editors do their jobs, says Sullivan.

“He said he wouldn’t talk to us because we were fake news,” says Sullivan, “but journalists are trained to overcome obstacles. In this business, not every interview is easy to get, but you just keep working at it until you get what you need.”

Despite the denigration of the media, bleak headlines and predictions about the news industry, there is reason for optimism. UNH, like other colleges across the country, is seeing an increased enrollment in its journalism program.

“Our numbers are up,” says Lisa Miller ’80, who directed UNH’s journalism program for 12 years. “These students realize that now more than ever there is a need for good journalists. And that is very heartening to me.”

While the basics of good reporting — accuracy, fairness and finding reliable sources and data — are still taught at UNH, the journalism program has also adapted to the demands and tools needed in jobs that require audio, video and social media skills.

“The definition of what a journalist is has broadened,” says Miller, who reported and edited at newspapers for nearly eight years before she began teaching journalism at UNH in 1989. “A lot of students coming through the journalism program want some kind of job that involves reporting and writing. They want to make a difference in the world, but they don’t necessarily want to sit in a newsroom to do it.”

Uncertain about pursuing a career in the media, students at UNH and other colleges often ask the Post’s Sullivan, “Is this a good time for me to get into journalism?”

And he answers with an emphatic: “Yes. Jump in with both feet.”

Despite the turmoil and uncertainty — perhaps because of it — Sullivan is among those who believe there has never been a more exciting time to start a career in the field.

“It’s just taking different forms,” Sullivan says. “There may not be a local paper in 20 years, but I believe young people are going to find new ways to tell local and regional stories. I don’t know what it is going to look like, but I’m absolutely sure someone is going to figure it out.”

TRAINING JOURNALISTS FOR THE DIGITAL WORLD

There is an old adage in journalism: “If your mother says she loves you, check it out.”

One of the basic elements of reporting is to verify facts, even if the news comes from a trusted source. And accuracy has never been more important in the era of “fake news” and public distrust of the media. But how do you verify information in the ever-expanding digital world of Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and YouTube posts?

“It’s all about sourcing,” says former UNH journalism program director Lisa Miller ’80. “I tell students to look carefully at the source of information they find online. If they can’t tell where it is coming from, that’s a red flag.”

In the late 1970s and early 1980s — when UNH journalism students still relied on typewriters — classes focused on interviewing skills, investigating tips and authenticating paper documents.

But since the creation of the internet and social media, courses have evolved to include verifying or debunking phony online posts, photographs and videos. When they first begin taking journalism courses, students tend to rely on one source, often a social media post for stories, explains Tom Haines, director of UNH’s journalism program.

“In general, it’s not part of our digital culture to look for the source of things,” says Haines. “These students have grown up for years with social media, and they are bombarded with information all the time. It’s hard to keep up with it all and say, ‘Wait a minute, how do I know if this is true?’ ”

The Verification Handbook is one of the popular texts used in classes. The book offers techniques and guidelines for how to assess and authenticate user-generated content.

Haines and his students recently reviewed a case study involving a woman who ran in the 2013 Boston Marathon and crossed the finish line just moments after the second bomb detonated.

“She recorded the joyous moment, 26 miles and then boom,” says Haines. “The video went viral and the organization Storyfold looked at how do we know this is legit?”

A news agency headquartered in Dublin, Ireland, Storyfold used several tools to verify the video, which was posted on YouTube with the username NekoAngel3Wolf. Storyfold searched Twitter and found a similar username, which provided other digital footprints on Pinterest and Facebook that led to the marathon runner’s daughter.

“Basically, they did what journalists have always done: get to the source and confirm the story,” Haines says.

When students report on their own stories for class or The New Hampshire, they are taught to cite their sources and how they got their information.

“It’s become more important than ever that our students go out and do journalism that people trust,” says Miller.

Along with learning verification techniques and tools, there are still a few relevant tips taught decades ago in Journalism 101. Students are encouraged to use good-old fashioned shoe leather: hit the streets and talk to sources.

“This is a different culture,” Haines says. “These students are used to talking through texts, but if you’re going to understand the story, you have to talk to people on the phone or in person, and Facebook messages don’t count.”

As visual storytelling and podcasts grow more popular, journalism will continue to evolve. In her classes, Miller has discussed virtual reality news with her students. Using techniques like Facebook live or virtual reality googles, viewers can be placed on the scene of a story.

With a generation that has grown up with smartphones and the ability to post photographs and video around the world within seconds, verifying online and social media news will become increasingly important. “The digital world for better or worse has become an extension of our world,” says Haines. “But what’s cool is that the journalist’s role is the same as it ever was: the authenticator, the verifier, making sense of this sea of information.”

-

Written By:

Barbara Walsh '81 | Freelance Writer