A villager in a Kapalamula neighbrohood works on the wall where a pipe will be fitted to provide residents with clean drinking water. Courtesy photo.

There’s a pipe that comes out of a cement wall in a village in Malawi that Emma Turgeon ‘19 helped put there. Before the pipe, there was a trench to dig, and the wall to build and a stone filtration system to lay down so the people of Kapalamula would finally have clean drinking water.

Turgeon, who graduates in December, led a small crew of UNH students in the design and implementation of the spring box filtration system that made that happen. She had been to Malawi before, on a volunteer trip during high school. When she learned she could create her own senior project at UNH, she knew right away that it would involve potable water.

“I had seen how desperate the people in Malawi were for clean water,” Turgeon says. “They were drinking from contaminated springs. They had virtually no access to health care. So many of them were malnourished; if they got sick from the water, they could die.”

“It was thrilling to be helping them. Going into it, I didn’t want to make something that couldn’t be replicated, so we did the ‘teach a man to fish’ thing instead of giving them the fish.”

Turgeon knew of professor Jim Malley’s research on clean water treatments and asked if he would be her faculty advisor on the project. He agreed, suggesting she bring in a few more students. Soon after, she recruited Anna Smith ’19 and Christina Eddleman ’19. All three are environmental engineering majors.

Turgeon and Smith traveled to Africa during winter break to do a scoping study — a practice established by Engineers Without Borders and adopted by Malley for his projects — that involves going to a location to gather information, evaluate logistics and forge relationships with community leaders before work begins.

In Malawi, the scoping studying found that some of the villages had hand-dug wells that ran dry off and on throughout the year as water levels fluctuated. So Turgeon and Smith turned to natural springs, most of which just looked like puddles.

“We knew it would be easy to create a spring box filtration system from one of them,” Turgeon says. In June, the pair, joined by Eddleman, returned to Kapalamula to implement the system. Quinn Wilkins ’19 who, with Engineers Without Borders, had previously helped create a similar clean water system in Uganda, acted as a mentor.

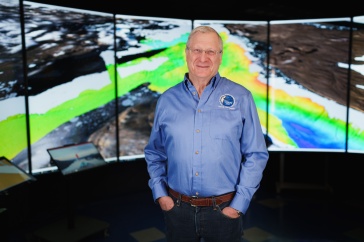

Christina Eddleman ’19, Anna Smith ’19 and Emma Turgeon '19 in Kapalamula

Over the course of four weeks and with help from the villagers, they chose a spring, excavated it, dammed it up and then dug a trench to the horseshoe-shaped cement wall where the pipe would come out.

“I was so excited to be part of their hard work,” Turgeon says. “It was thrilling to be helping them. Going into it, I didn’t want to make something that couldn’t be replicated, so we did the ‘teach a man to fish’ thing instead of giving them the fish.”

The project wasn’t without its glitches. Plans called for using shock chlorination to disinfect the gravel in the filtration system, and that required unscented bleach. They had to drive to Lilongwe, the capital, which was an hour and a half away, and visit three stores before they found any. Next they needed hydraulic cement for the wall; regular cement leaks and takes too long to set, Turgeon says.

“But they don’t have hydraulic cement anywhere in the country,” she says. “So we were working in the mud, in a sloppy mess. We solved the leakage problem using natural clay — tons and tons of clay.” And they phoned home. “A few times we called Tom Ballestero (associate professor of civil and environmental engineering) to find solutions.”

Ballestero, Malley and Robin Collins, both professors of civil and environmental engineering, had helped the team design the spring box system. A grant from the UNH Emeriti Council Student International Service Initiative helped fund the project.

“My biggest concern was to fit into their culture,” Turgeon says. “I didn’t want to just cater to their needs; I wanted to create something that they could do. By the end of the project, we’d be walking back to the guest house and people would stop us to see how we could help them. One man spoke English and asked if we were going to get them water. We told him we had taught the other villagers how to do it and they would teach them. That was a great moment.”

-

Written By:

Jody Record ’95 | Communications and Public Affairs | jody.record@unh.edu