New research from UNH has found that horseshoe crabs, whose blue blood is harvested by the biomedical industry for its unique ability to test devices and injectable drugs for contamination, spawn less and remain in deeper water after being bled. The findings suggest that current bleeding practices could alter population dynamics and lead to long-term declines in this ecologically and economically important species.

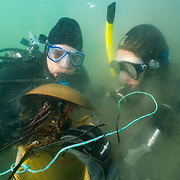

Owings and Watson Photo by Steve de Neef

“Their mating behaviors were impacted, and their activity decreased” after bleeding, says Meghan Owings ‘17G, lead author of the study published in The Biological Bulletin. “We saw a lot of behavioral as well as physiological deficits.” During the process, around 30 percent of a crab’s blood is extracted before it is returned to its natural environment.

Horseshoe crabs are essential to the biomedical industry to create Limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL), which is used to test medical devices and pharmaceutical drugs for endotoxins.

“If you were to get a flu shot or IV fluids, it would be tested with horseshoe crab blood,” says Owings, adding that the demand for LAL is on the rise as the global population increases and medical advancements improve.

The paper, coauthored by Professor Emeritus of biological sciences Win Watson, who is Owings’ advisor, and Christopher Chabot of Plymouth State University, is one of the first to look at behavioral impacts of the bleeding process on horseshoe crabs once they’ve been released back to the wild.

“If you were to get a flu shot or IV fluids, it would be tested with horseshoe crab blood.”

Owings and her coauthors retrieved 28 horseshoe crabs — 450-million-year-old “living fossils” more closely related to spiders than crabs — from a spawning site in nearby Great Bay. Half of the crabs were randomly selected to undergo the bleeding process, and all of them, both bled and control crabs, were fitted with acoustic transmitters and released where they had been captured.

The researchers found that in the first week that the animals were released back into the estuary, bled animals appeared to spawn less than the control animals. The difference was especially pronounced in females, with control females appearing to spawn on average 4.8 times while bled females appeared to spawn on average two times.

Watch a video of this research produced by Hakai Magazine.

Another notable trend was that in May and June, when horseshoe crabs typically move into shallow water to spawn, the bled animals remained in the deeper channels.

“It seems really harmful for the horseshoe crabs to be bled during the spring mating season,” says Owings, adding that some biomedical facilities have slightly altered their bleeding practices based on the team’s findings.

Now a fisheries biologist for the Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources, Owings still has a soft spot for the hard-shelled beasts. “I loved working with horseshoe crabs at UNH,” she says.

Watson, who recently retired from UNH after 41 years of lobster and horseshoe crab research, shares his advisee’s admiration and concern for the crabs’ survival. “These guys have been around for 450 million years,” he says. “Do we really want to be the ones responsible for their demise?”

This study was supported by the Leslie S. Hubbard Marine Program Endowment, the Marine Biology Graduate Program and New Hampshire Sea Grant (R/HCE-4).

-

Written By:

Beth Potier | UNH Marketing | beth.potier@unh.edu | 2-1566