Editor's Note: This is the latest in a series featuring UNH faculty telling their stories in their own words.

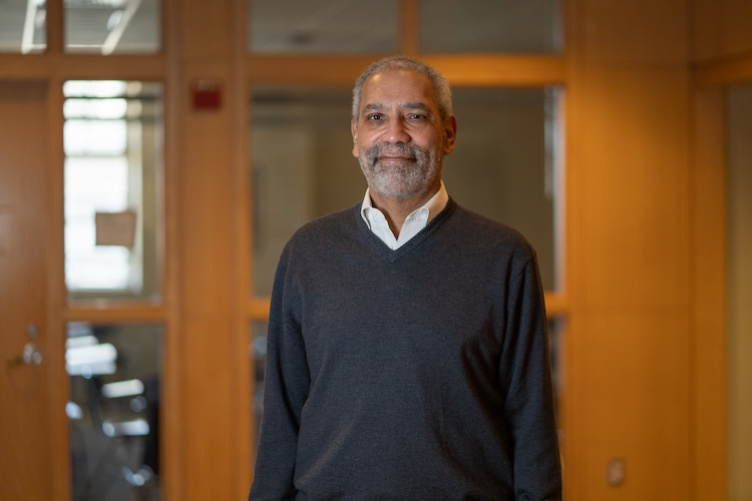

Vernon Carter, associate professor, social work

"I’m the great-grandson of a slave. My father’s grandmother had been a slave in Virginia. Both of his parents attended historically black colleges and universities in the south. My paternal grandmother graduated from the Hampton Institute in 1915. My paternal grandfather graduated from Prairie View A&M in Texas the same year.

My mother was born on a dairy farm in upstate New York. She was the daughter of a tenant farmer. Most of her siblings — she was one of 13 —went into the military, the men and the women. She dropped out of school in the 10th grade and ended up moving to New York City to work in a war factory during World War II. My father was born in New York City. He was a soldier, and he met my mother at one of those military dances. After that, he became a truck driver.

I was born in Harlem Hospital and grew up in a project in the north Bronx that was predominately Jewish. The school system in New York City was incredibly racist. It came to a head when I was in the sixth grade. There was a special program for bright kids, and I was bright, but they wouldn’t let me in. It wasn’t open to “this colored person because I didn’t work hard enough.” When I was 16 my parents sent me to live with my maternal grandmother on the tenant farm. I had spent every summer of my life on the farm so I knew what to expect. Because they were tenant farmers, there wasn’t the same expectation for me to work that there would have been if they owned it.

I went to high school in Washingtonville, New York. One of the ways the senior class raised money was through slave sales, of whites and blacks. You bid on someone and they were your slave for the day. The symbolism was dramatic. There were two girls, twins from Georgia, who said that if they got me, they were going to have me sing “Dixie.” Two black girls outbid them.

In 1968, after high school, I went to Orange County Community College in Middletown, New York and majored in chemical engineering. It was close to the Hudson and IBM was in the area. At that time, they were scooping up everybody with a science background. I didn’t want to work for Big Blue so I switched my major to literature. Then I transferred to Oneonta SUNY (State University of New York) to finish my undergraduate degree. I stayed in Oneonta for a few years and worked at many different jobs —I was a bag boy, a school bus driver, a substitute teacher and a darkroom assistant at a newspaper.

I moved to Kittery, Maine, in 1973. I was married and had a child who had a rare eye disorder and there were only three doctors in the U.S. who treated it. One was in Boston. I had a friend from college who lived in the seacoast area, so we stayed with her until I found a place to live. I took whatever I could get for work — mason’s helper; construction; a safety specialist at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard. In 1976, I opened a bar called the Common Crossing in Portsmouth with a few of friends. There weren’t a lot of places for young people to go then, so it seemed like a good idea even though we didn’t know anything about running a bar. It was only open for a couple of years.

After that, I got a job as a personal care attendant for an elderly gentleman and did that for 5 years. When he died, I went to work at a group home for people with developmental disabilities. Over the next few years this led to me obtaining several jobs in this field in New Hampshire and Massachusetts. I did that through 1986 and left for a job as an insurance claim examiner for a year. I quit that to be a child protective worker without any idea what a child protective worker was or did. Because of my background working with people with disabilities, the state decided I was a social worker even though I hadn’t ever taken a social work or psychology class. I was hired as a social worker II and ended up being a supervisor. I loved it and kept that job for 13 years. In the meantime, I had watched people getting laid off whose backgrounds were like mine and they couldn’t get hired back because the credentialing had changed. So, in 1994, I decided to get my master’s degree at UNH. It took me four years.

In 2001, I was hired by the New Hampshire public defender’s office to start the first social work program in the state. My emphasis was on substance abuse. I went into jails, prisons and treatment facilities. It was a great job. In the ‘80s and ‘90s, treatment programs popped up like mushrooms. Then the insurance companies figured out it wasn’t profitable enough and they all closed.

I had already begun working on obtaining my doctorate. I had stipulated when I was hired by the public defender’s office that they would give me the freedom to do that. I went to Boston College — that was one of the few places you could go part time and I was working full time; I had three children and a partner. I loved that job. There were a lot of challenges interacting with the incarcerated, correctional officers, treatment programs and the court systems. Most of the time people were happy to see me. The public defender’s office really valued social workers. And the people who were incarcerated saw me as a lifeline to the outside world.

I got my Ph.D. in 2003 and was hired by UNH on the tenure track."