Like many New Hampshire peaks, Mount Chocorua bears an indigenous name and legend.

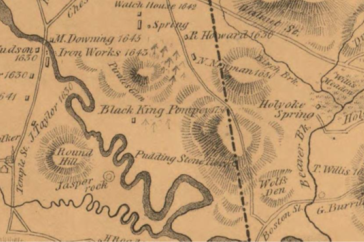

UNH anthropologist Meghan Howey has a 1667 map by an English merchant that shows dozens of colonial homes, churches and mills along the Oyster River and other tributaries leading to Great Bay. These were the early English settlements that would eventually comprise New Hampshire’s Seacoast region. Missing from this landscape are the people who had inhabited the place for millennia.

While their language is inscribed in modern names of rivers, mountains and cities, they and their heritage are often overlooked.

“We need to move beyond powwows and provide resources people can use to understand our daily lives.”

But they were there, and they’re still here today. Two of them, Paul and Denise Pouliot from Alton, N.H., members of the Cowasuck band of Pennacook Abenaki People, are working alongside Howey and other UNH researchers to recover their history and give it a new voice in the present. Indigenous New Hampshire is the umbrella name for this collaboration, which involves community members, students and UNH faculty members, including anthropologists Howey and Svetlana Peshkova and English professor Siobhan Senier. Together, they are patiently amassing a rich, interdisciplinary “archive” of indigenous New Hampshire cultural heritage.

On the shores of Oyster River, Howey is directing an archaeological dig that’s uncovering not only stone foundations and artifacts dating to the 1630s, but also fresh glimpses into the impact of European settlement on the people and place. The presence of native artifacts, such as stone tools found in the hearth of an English family house, tells us “that settlers and natives weren’t always at each other’s throats. The settlers, in particular, depended on indigenous peoples,” says Howey, who is the James H. Hayes and Claire Short Hayes Professor of the Humanities.

Indigenous collaborator Paul Pouliot says there’s been a recent uptick in seeking a deeper understanding of indigenous culture that attracts native and non-native peoples alike. “We need to move beyond powwows and provide resources people can use to understand our daily lives,” he says. To this end, the Pouliots are also working with Peshkova to build the Indigenous New Hampshire story map, “an online reinterpretation of key events and the places where they occurred from a Native American perspective,” in Peshkova’s words.

The project offers fresh insights into such cultural icons as the Old Man of the Mountain and events such as the 1694 Raid on Oyster River (also called the Oyster River Massacre) and has drawn strong interest from teachers in New Hampshire schools.

So, too, has Dawnland Voices, an online journal launched in 2012 by Senier. Together with tribal authors and editors from around New England and colleagues at Bryant College and the universities of Maine and Massachusetts, Senier publishes a wide range of original writing. “One of the magical parts of producing Dawnland Voices is the power of memory uniting the people living today with those who came before them,” says Senier. “They are voices of endurance and strength.”

In addition to making indigenous resources broadly accessible, the collaborators also want to model a partnership built on trust and understanding, despite cultural differences. Explains Howey, “You have to learn to sit with discomfort, knowing that we may not always be able to fully reconcile scientific and spiritual connections to artifacts but will still respect each other.”

-

Written By:

Dave Moore | UNH Cooperative Extension