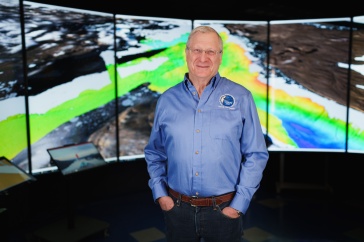

Courtesy photo

In the Arctic, the bald eagles soar like seagulls, they’re so plentiful. Polar bears swim in the frigid water. And being on the ice, says Cameron Carbone ’20, is like being in another world, on another planet.

Those firsthand descriptions aren’t known to many college juniors. Carbone says more than once that he feels lucky to have been witness to such wonders. In September 2018, he was invited by Dale Chayes, affiliate professor with UNH’s Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping (CCOM), to join more than 25 scientists aboard the polar icebreaker the U.S. Coast Guard cutter Healy as it ventured to the Arctic. The six-week trip was part of a five-year research initiative known as the SODA (Stratified Ocean Dynamics in the Arctic) project, launched to increase understanding of the region’s diminishing ice pack.

“To be able to go into the Arctic Circle onboard an icebreaker and deploy some serious R&D scientific instrumentation on a worldwide project — it was an amazing opportunity.”

The Healy is the U.S.’s newest and most technologically advanced icebreaker. With 4,200 square feet of scientific laboratory space, and capable of accommodating up to 50 scientists, it is also the Coast Guard’s largest research vessel.

“I knew it would be the trip of a lifetime,” Carbone says. “To be able to go into the Arctic Circle onboard an icebreaker and deploy some serious R&D scientific instrumentation on a worldwide project — it was an amazing opportunity.”

Carbone worked at CCOM during the summer to help Chayes prepare for the trip. The ocean engineering major had no thoughts of actually going along; he was a part-time employee helping a researcher. In the fall, he would resume his classes. But then Chayes told Carbone there was room on the ship if he wanted to make the voyage.

“I had to forgo the fall semester to do it, but it was totally worth the tradeoff,” the Sterling, Massachusetts, native says. “It put me back a semester, but I was able to categorize the trip as work experience and enroll under our Tech 697 industrial experience class, which allowed me to keep my full-time student status.”

Part of the pre-trip work he and Chayes did tested the underwater acoustic calibrations of the multibeam sonars that would be used to map the underside of the ice caps in the Arctic for a full season. Set 100 feet below the water’s surface, the sonars track how sea ice forms and moves.

“People think the underside of the ice is flat, but that’s not true,” Carbone says. “This research will provide a better understanding of the ice life, the new and the old. There's a good chance that by the end of this century there won’t be any ice during the summer months, so I was pretty wowed to see it in person.”

The Healey’s homeport is in Seattle, but the ship spends much of its time in the Arctic. The SODA project was one of three undertaken during its four-month excursion, conducted in partnership with the National Science Foundation, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Office of Naval Research. Changes in the upper ocean stratification in the Beaufort Sea, north of Alaska, and the Chukchi Sea that borders Russia to the west and Alaska to the east, sparked the research, along with an observed increase in open ocean water during the summer months.

“We departed from Dutch Harbor (Alaska) on Sept. 14 and returned on Oct. 19. Door to door, the trip took about 6 weeks,” Carbone says. “Travel was long, flying from Boston to Seattle, Seattle to Anchorage and then Anchorage to Dutch Harbor."

While on the ship, Carbone says much of the time was spent creating lithium battery packs for the multibeam sonars, noting, “A lot of power was needed for a full seasonal cycle.” On ice station days, he helped offload gear from the helicopter deck that went to each station. He then helped bore holes through the ice for the equipment that measures the flux patterns and stratification in the upper water column beneath the ice. The whole process took about seven hours each day. Lunches were brought to the team by sled.

“We were out there,” Carbone says. “Once we started working, we didn’t stop. There were long days on the ice. You needed to be physically prepared as well as mentally.”

Later this year, a second excursion will recover the instruments left behind. Carbone likely won’t be there, but he says the time he spent in the Arctic helped him get closer to knowing the kind of work he might do in the future.

“Wherever I land for a career, I know I want to be doing work that benefits the Earth and humanity,” Carbone says. “There will always be challenges that lie ahead with climate shift directly related to the Arctic, but it’s what we as scientists and engineers do to prepare for this future that really matters. Our decisions start with extensive research on where the Arctic is now, and to be able to be a part of that was really special.”

Learn more about ocean engineering at UNH.

-

Written By:

Jody Record ’95 | Communications and Public Affairs | jody.record@unh.edu