Since the arrival the colonists, an unsettling trend has been affecting the Indigenous people of North America and has largely been ignored until very recently: the epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous people.

In 2010, the Department of Justice released a report that illustrated just how much of an epidemic violence is among American Indians and Alaska Natives; it revealed that more than four out of five Indigenous women and men experience violence in their lifetimes. On some reservations, Native women are murdered at more than 10 times the national average, and homicide is the third leading cause of death among 10- to 24-year-olds. Native American women are also twice as likely to experience rape or sexual assault in their lifetimes.

And no one knows just how many Indigenous women, children and LGBTQIAP2s+ people have gone missing, due to the failure of tribal court systems, police and the FBI to keep track.

One activist, a Southern Cheyenne doctoral student and survivor of sexual assault and domestic violence named Annita Lucchesi, decided to start her own database using information she collected from news reports, law enforcement data, government missing persons databases and stories shared by families and community members from 1900 to the present day in both Canada and the United States. As of April 2018, the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women database includes 2,501 cases and still counting.

Part of the problem stems from Indigenous courts being unable to prosecute people who are not tribal members for their crimes, an issue partially addressed in the 2013 Violence Against Women Act regarding cases of domestic violence. However, not all tribes practice this jurisdiction, and other acts of physical and sexual violence were not covered by the act. And the many cases of missing and murdered Indigenous people are just not priority to law enforcement and government. In 2015, Canada launched an inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, which included transgender and two-spirit people. But as the inquiry went on, Indigenous communities failed to see any real action apart from data collection. A letter from community members in response to the government’s request for an extension of the inquiry states, “A recurring narrative from communities has emerged: They came; they took stories; they left.”

In the United States, lawmakers have failed to successfully address the epidemic, but for the first time for the centuries-old issue, legislation is finally beginning to emerge in several forms — most prominently in the proposed federal bill Savanna’s Act, introduced by South Dakota Sen. Heidi Heitkamp in October 2017. The bill was named after a 22-year-old member of the Spirit Lake tribe who was eight months pregnant when she went missing from her Fargo home in August 2017. Her body was found a week later, and it was discovered that she had been murdered by neighbors who had kidnapped her.

Savanna’s Act would add tribal affiliation to federal databases that could help keep track of missing Indigenous people, with data reports being submitted annually. It would also require the Department of Justice to develop a standard protocol for addressing those cases of missing and murdered indigenous people.

But as illustrated by what happened when Canada introduced similar efforts, some Indigenous people are skeptical whether those who created the problem could be the ones to fix it. As Lucchesi, the woman who started the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Database, puts it, “I don’t think you can fix problems that have been created by poor legislation with more legislation rooted in the same way of knowing and in the same culture.”

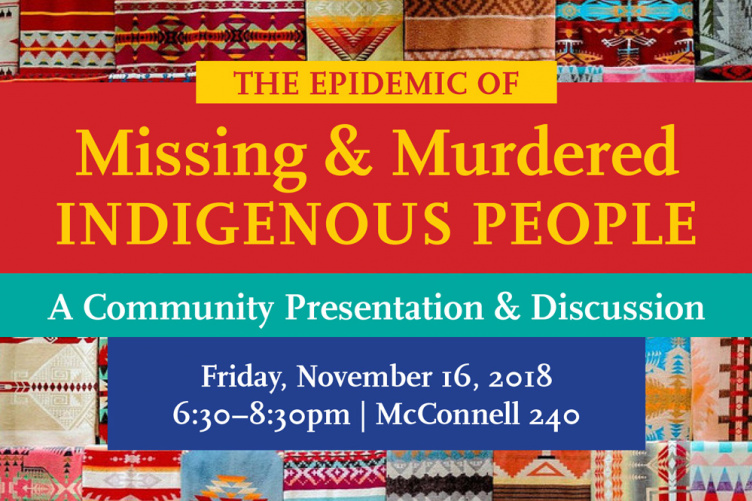

This issue has gone unnoticed by our mainstream social justice community for far too long. That’s why SHARPP is partnering with the Native American Cultural Association (NACA), the women’s studies program and the anthropology department to raise awareness about this epidemic throughout the month of November in honor of Native American Heritage Month. We hope you’ll join us on Friday, Nov. 16, at 6:30 p.m. in McConnell 240 for a special collaborative presentation and discussion event on the epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous people, where we’ll hear from experts and discuss ways that we as a community at UNH can address the problem.

And throughout the month of November, NACA will be collecting donations for the Coalition to Stop Violence Against Native Women, an organization dedicated to raising awareness about and addressing the issue of violence against Indigenous people. Click here to make your contribution.

-

Written By:

Jordyn Haime '20 | SHARPP Student Marketing and Communications Assistant