(left to right) Paul Pouliot, Denise Pouliot and Grace Dietz at an internship presentation.

When it comes to telling the stories of indigenous people in New Hampshire, the “official” history — found on historical site markers, in text books and on public murals, among other places — only tells part of the story.

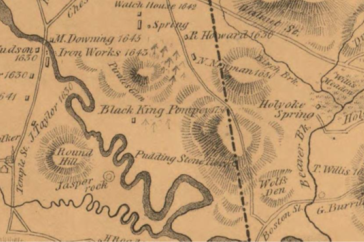

Grace Dietz ’17 learned that firsthand during an internship this semester with Paul and Denise Pouliot of the Cowasuck Band of the Pennacoook Abenaki People. Dietz was the first student intern to work on a long-term collaborative project between the Pouliots and the anthropology department to reframe Granite State history from an indigenous perspective by mapping indigenous sites of cultural and historical significance.

“New Hampshire’s history is partial, and it’s written by the victors,” said Dietz at a presentation about her internship in April. “Because of this, we misrecognize indigenous cultures and peoples as they are now — we expect to see something that’s not there because of our own stereotypes and what’s in our imaginations.”

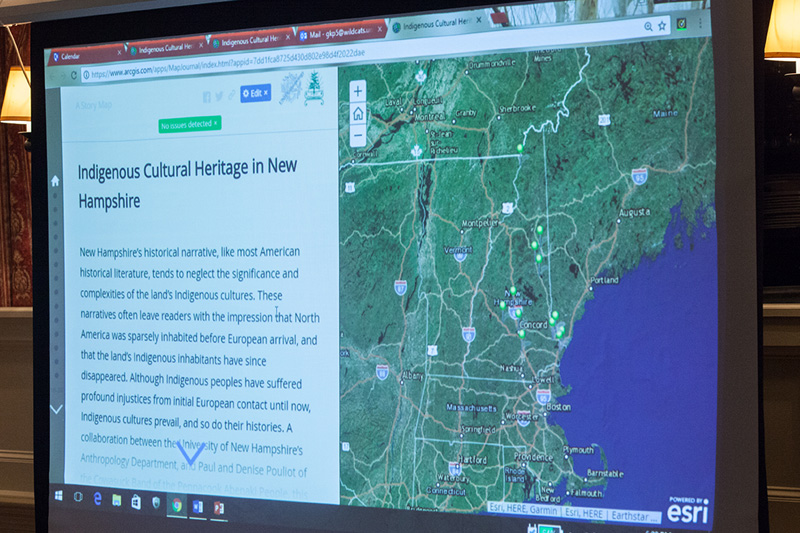

Dietz, an anthropology and international affairs major, worked with the Pouliots on a “story map” of New Hampshire’s indigenous history. The project combines the latest maps with text, images and multimedia content to create a narrative that spans thousands of years and hundreds of miles.

“We see this as a great start to telling the history of New Hampshire in a broader sense and not just a colonial perspective,” Paul Pouliot said.

Using archival research and interviews with Paul and Denise Pouliot, Dietz created a story map highlighting more than a dozen locations important to indigenous history throughout New Hampshire. Explore the map and you’ll find entries on Abenaki chief Joseph Laurent, whose 1884 book “New Familiar Abenakis and English Dialogues” was the first Abenaki-English dictionary. That same year, Laurent opened the Abenaki Indian Shop and Camp in Conway as a way to capitalize on tourism in the area and give members of the Abenaki community a place to sell items and trade stories. Other entries examine the tales surrounding the naming of Mount Chocorua, legends about the creation of Amoskeag Falls (located in what’s now Manchester) and the 1689 raid on Cocheco (now known as Dover).

“The story map is an ongoing collaboration,” Dietz said. “We don’t have the whole state, we don’t have everything (mapped on it), but we’re at the beginning of looking at our local history from another perspective.”

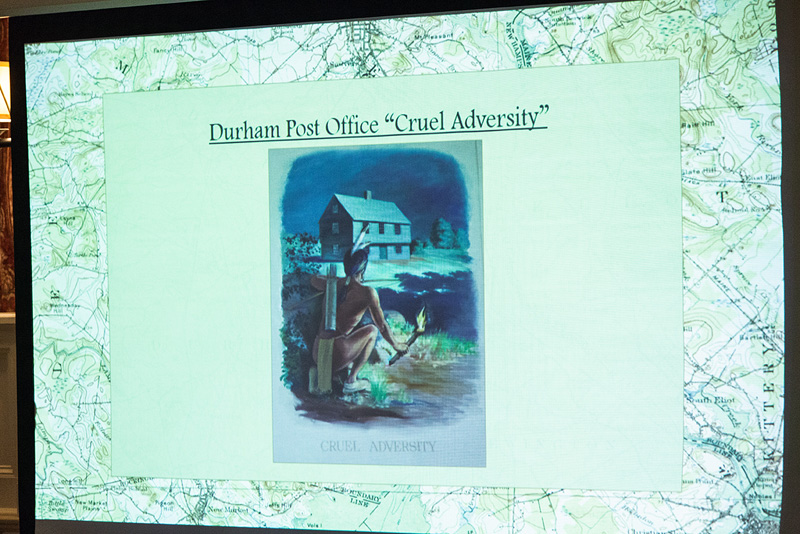

According to Dietz, finding examples of how easily indigenous history has been and continues to be distorted is as easy as walking through Durham. The map includes entries on the historical highway marker commemorating the Oyster River Massacre of 1694 and the 16-panel mural in Durham’s post office that features an indigenous man about to set fire to a settler’s home alongside the caption “Cruel Adversity.”

Reading the marker and looking at the mural reduces Native peoples to a flat stereotype and minimizes the complexities of history, Dietz said. Rather than explaining the complicated social, political and environmental relationships between indigenous people and English and French settlers, items like the mural and marker overly simplify and obscure history.

“A lot of these battles and attacks had a lot to do with resources and land, and how, after settlers had been here for a while, the landscape of New England itself had changed,” Dietz said. “So many indigenous people weren’t able to exist the way they had been before because of those fundamental changes.”

For Denise Pouliot, the story map is a chance for New Hampshire residents and others to see local history in a more holistic way. “I’m happy the Abenaki are finally getting a say in what their history has been, instead of being told what their history is,” she said. “It’s nice to see the English perspective and the French perspective and the Native perspective and how they’re all different from each other.”

Sventlana Peshkova, associate professor of anthropology, is guiding the collaboration between the Pouliots and the university. In 2016, Peshkova received one of the UNH Center for the Humanities’ first Publicly Engaged Humanities Fellowships to develop student internships in cultural heritage.

Dietz hopes other students will carry on the work she started with Paul and Denise Pouliot. There are hundreds more important locations, events and people in New Hampshire to document, along with hundreds of misconceptions and stereotypes about indigenous people to dispel.

“The goal of it is to make the information more accessible to the public — there’s no point in keeping it within academia. This is just the beginning of getting everyday people to think about history more critically,” Dietz said.

Students, faculty, staff and administrators attended Grace Dietz's internship presentation.

-

Written By:

Larry Clow '12G | UNH Cooperative Extension