Imagine this: It’s a Sunday night and you’re at home. You’ve whittled your to-do list down to one item — all that’s left to do is clean up the dinner dishes. You load the dishwasher and, pleased with your productivity, decide to treat yourself. A movie is in order — in fact, it’s the perfect night for a monster movie. You sprawl on the couch, pull out your phone, and search Amazon for 2014’s “Godzilla,” the one with Bryan Cranston from “Breaking Bad.” This, you think, is perfect: a slice of domesticity that couldn’t be farther away from the buzz of activity at UNH.

Don’t be alarmed, but you’re totally wrong.

Washing the dishes, using your phone and even that big-budget monster movie: there’s a little bit of UNH in all of them. That’s thanks to UNHInnovation (UNHI), the campus department that promotes, manages and advocates for the intellectual property created by the university’s students, faculty and staff. Or, as Marc Sedam, associate vice provost of innovation and new ventures and UNHI’s managing director, says, UNHI takes all the great ideas created at the university and makes sure they’re put to use in the wider world.

That’s how polymers from itaconic acid, developed by the New Hampshire-based start-up company Itaconix Corporation, co-founded by then-materials science associate professor Yvon Durant, wound up in your dishwashing detergent. And it’s why major wireless companies use internet protocol tests verified at the InterOperability Lab to keep your cell phone working. And it’s how the first-of-its-kind map of the Mariana Trench, developed by the University’s Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping, made a cameo appearance in “Godzilla.”

“If you think of the university as an in-bound entity — we take in students, take in funding, take in faculty — (UNHI) is the place that’s 100 percent externally-focused,” Sedam says. “We’re pushing our ideas out to the market, engaging with the business community and engaging with the needs of the state. Our job is always looking outwards.”

Searching for serendipity

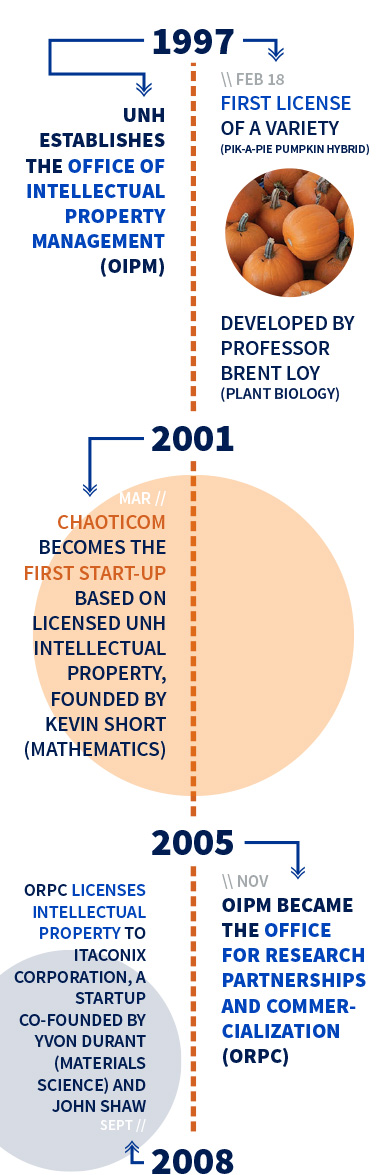

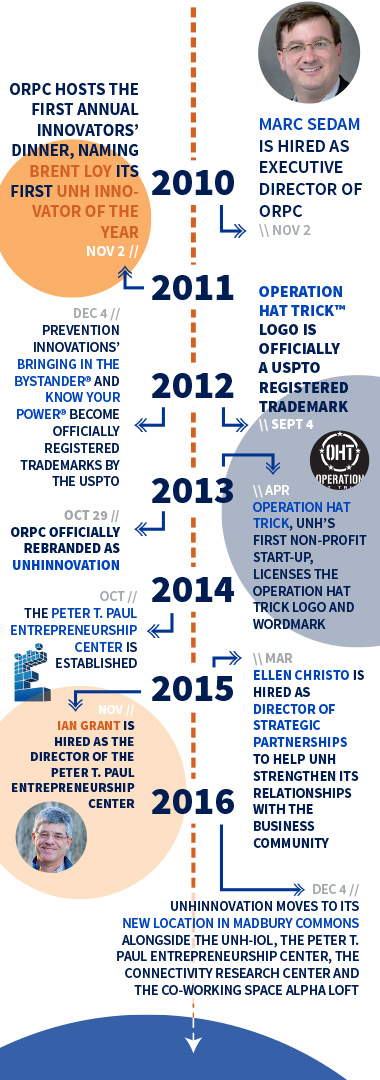

What UNHI is looking for is, in a sense, serendipity: matching up ideas, processes, devices, companies, curricula and everything else developed at UNH with an array of users across the globe. Formerly known as the Office for Research Partnerships and Commercialization, UNHI went through something of a metamorphosis two years ago, Sedam says. What emerged was a department focused not just on traditional intellectual property licensing but on matching up university services with the private sector and helping start-ups founded at the university to successfully launch.

Before UNHI, the university “didn’t really have the other pieces of the puzzle,” Sedam says. “What would lead to the creation of an idea, how would you incentivize an idea, how would you get the faculty to even know they have a (commercial) idea? Invention is serendipitous, and part of our objective was to get faculty to understand when serendipity is about to happen.”

That moment can happen in thousands of ways. Maybe it’s talking with a New Hampshire company that needs a scanning electron microscope for a project and renting out the equipment for a short time. Or maybe it’s licensing one of plant biology professor J. Brent Loy’s new squash varieties to a seed company.

The idea, Sedam says, is to get as many UNH-derived ideas out into the world as possible. “We don’t necessarily focus on money; we focus on use. If we maximize the use and there’s money to be made, great, we’ll make some money. But if you try to maximize the financial return, you may get some money but you may not have anybody ever use the idea — and which one has a bigger effect on the world?”

Innovators, not inventions

Talk about intellectual property, technology licenses and start-up companies for any length of time and it can get a bit technical. But people are at the heart of all those advances.

“We don’t just focus on inventions but on innovations,” says Maria Emanuel, associate director of UNHI. “We want people to understand that, across every discipline … we have innovators. It’s throughout the entire culture we have here.”

Emanuel coordinates licensing at UNHI. The details are complex, but the principle is simple: The university leases out an idea — a new invention, an innovative curriculum or a killer concept for a start-up — to a company. The license can be a long-term exclusive license to that company, a short-term license for multiple companies or something in between. When Sedam started at UNH in 2010, the university had eight active licenses with outside companies; in 2015, it had about 350, which he believes puts UNH in the top five universities in the country for total number of licenses that year.

“Commercialization is important to get (ideas) into broader hands … but what we’re getting out there is a highly valuable innovation that’s based on expertise and the years of research that’ve gone into creating it. If you just freely release some of these innovations, that value can get diluted very quickly as people make improvements that aren’t evidence-based or research-based,” Emanuel says.

Licensing helps keep the university’s research ecosystem thriving. It disseminates the hard work and years of research done by faculty, staff and students. That, in turn, increases the university’s reputation and prompts more companies to license ideas from UNH, recruit students or partner with alumni on new ventures. The results ripple out in ways big and small, impacting the New England region and the world.

“We don’t necessarily focus on money; we focus on use. If we maximize the use and there’s money to be made, great, we’ll make some money. But if you try to maximize the financial return, you may get some money but you may not have anybody ever use the idea — and which one has a bigger effect on the world?”

“I love Brent Loy’s story,” Emanuel says. “His research really solves problems and meets needs for New England growers, but his pumpkin and squash varieties are sold throughout the world. That’s a really impactful story, particularly for a land-grant institution. … And the outputs are really delicious.”

Changing lives

One of UNHI’s most notable success stories is Operation Hat Trick (OHT). Founded in 2007 by then-senior athletic director and current athletics licensing director at UNHI Dot Sheehan ’71, Operation Hat Trick started as a fundraiser for wounded veterans, selling UNH-branded hats locally and donating the proceeds, along with the hats themselves, to veterans recovering from head injuries at VA medical centers.

Operation Hat Trick proved to be popular — it became an annual event and, in its peak year at UNH, raised some $3,000. When Sedam arrived at the university in 2010, though, he saw the potential for something more.

“It was a start-up to me. It was totally scalable and it was a big idea,” he says. Other universities were taking notice, too — they wanted to run their own OHT fundraisers, but the logistics were difficult. The solution turned out to be simple. OHT became a non-profit and licensed logos and trademarks from the university, which it then in turn licensed to other universities, retailers like Wal-Mart and sports organizations like the National Hockey League and NASCAR.

Last year, OHT had $3.2 million in retail sales and worked with some 275 licensees. The proceeds go to wounded veterans, helping pay for life-changing projects of every size. OHT was an early supporter of former Army Staff Sgt. Travis Mills’ efforts to open a camp in Maine for veterans with disabilities; it also paid for a custom-made bow for a veteran who recovered from his injuries through an archery program.

“You do something like that, and the money doesn’t matter. You honestly help people in a legitimate way,” Sedam says.

Launching success

The future of innovation at UNH might look something like Operation Hat Trick: an idea born and nurtured at the university and then sent out to change the world. For Ian Grant, there are countless other start-up opportunities similar to OHT in the worldwide university community, from new businesses founded on campus to alumni taking over and expanding an existing business across the globe.

Grant is the director of the Peter T. Paul Entrepreneurship Center — its mission, he says, is to help students, faculty, staff and alumni realize that they’ve got a great idea for a company and provide them with the tools to launch a successful business.

“We don’t just focus on inventions but on innovations. We want people to understand that, across every discipline … we have innovators. It’s throughout the entire culture we have here.”

The ECenter, as Grant calls it, is a sort of microcosm of UNHI’s larger efforts. Through its Wildcatalysts program and its partnership with Alpha Loft, the ECenter offers workshops, meet-ups and mentoring sessions for students, faculty and staff who are ready to launch a new company. It also offers two 10-week “business boot camp” sessions for start-up founders and is the place to go if you’re looking for an angel investor or need advice on a business plan.

Faculty, alumni and students “have a trusted source internally that has their best interests at heart,” Grant says.

But more than that, Grant says the ECenter’s mission is to cement a culture of entrepreneurship on campus. It’s not just start-up companies and venture capital — it’s an attitude and a skillset, one that empowers students to notice a problem, identify it and come up with a series of potential solutions. Entrepreneurship crosses disciplines, according to Grant. It’s a skill that’s just as valuable for artists as it is for software engineers.

“It’s a tool that every student should leave UNH with in his or her toolbox; you need it no matter what you do,” he says.

A return to roots

UNHI moved into its new home in the Madbury Commons building in downtown Durham in early 2016. The location is purposeful — Sedam says it’s an example of how UNHI connects the university with the town, the state, the region and the world.

“We’ve got the talent here and we’ve created an environment where people can work on those ideas,” he says. “This is a great first step, but it’s not the end; it’s the beginning. We’re going to create ideas that are going to change the world, but they start small and need to grow. We have limited space, and that’s intentional. Our objective is to get things started.”

The emphasis on technology, licenses and start-ups may sound far from the university’s traditional mission, but Sedam sees it as a return to the ideas that UNH and other land-grant institutions were founded on. When the Morrill Act created land-grant universities in 1862, “it wasn’t a knowledge play; it was an economic development play,” Sedam says. The country was expanding and agriculture was giving way to the industrial revolution. Land-grant universities were there to give people the knowledge and tools they needed to prosper.

“Now, all we’re doing is replacing plows with patents and cows with copyrights. We’re saying the same thing: How do we get those ideas out into the world and make things better?” Sedam says. “We’re paying homage to our founding and our roots but in a very 21st century way.”

Originally published in UNH Magazine Spring 2016 Issue

-

Written By:

Larry Clow '12G | UNH Cooperative Extension