Editor’s note: ISIS has taken responsibility for Tuesday’s explosions at an airport and a metro station in Brussels that killed 34 people and injured more than 200. It is the latest claim in a wave of terrorism since ISIS began its deadly assaults outside of Syria and Iraq.

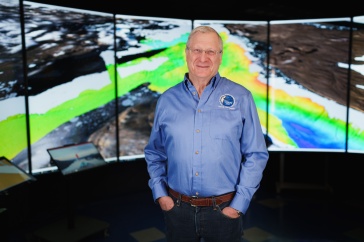

UNH Today spoke with UNH Manchester's homeland security expert Jim Ramsay, professor of security studies, and Melinda Negrón-Gonzales, assistant professor of politics and society, about the recent attacks.

When Jim Ramsay walked into his classroom at UNH Manchester Tuesday morning, he set aside his planned lesson and asked students to talk about the terrorist attacks in Brussels.

What does your gut tell you? What’s going on? That's what Ramsay, a professor of security studies and a leading authority on homeland security education, asked his students. He was, he says, trying to create perspective, noting, “Bad guys have always been on the planet.”

And that’s true. The word terrorism, meaning to use violence or intimidation to further a political, religious or ideological goal, was first recorded during France’s Reign of Terror in the late 1700s when more than 16,000 people were beheaded. In recent years, the strategy — if that’s what it is — has still employed that barbaric act as well as mass bombings and suicide bombings.

“There was obviously a lot of frustration and anger. Everyone asked ‘Why?’” Ramsay says of students’ reaction to the killings in Belgium. “But that’s an illogical question because it’s predicated by a group’s trumped-up ideology — they’re using God as an excuse for what they’re doing when maybe the answer is just that there are people who want to see the world burn.”

Melinda Negrón-Gonzales, assistant professor of politics and society and coordinator of the politics and society program at UNH Manchester, puts it another way, suggesting maybe it has nothing to do with religion. Maybe the weight of feeling disenfranchised, of feeling they have no voice, no power, has led people to join these groups that offer them a place to belong.

“We know that a fair number of people drawn to ISIS are not particularly religious. There is a theory out there that a lot of these people are sort of drifters, or second and third generation immigrants who feel they aren’t being treated fairly. People become radicalized because they are looking for a place to vent their anger,” says Negrón-Gonzales, who teaches the class Political Violence & Terrorism.

“Scholars of terrorism are less focused on ideology than the root causes — what lets someone be susceptible. People want to belong to an important group. There is something missing in their life so they want to become someone, become a leader — especially young men who become empowered by joining groups. They lose sight of religion. It’s about feeling manly.”

And those feelings aren’t something that will change by carpet bombing ISIS or closing our borders to Muslim immigrants, the professors say.

“We are a nation of immigrants. You can’t turn back the clock. You don’t fight a global threat by becoming isolationists,” Ramsay says. “We need to do exactly what world leaders did in response to this recent attack. We need to stand united; we need to join forces; we need to be together on this.”

“How we fight them is to make them less relevant,” he adds. “You have these people who don’t have anything to do, who can’t feed their families, who are suffering from shortages, who are armed, and they go and do what we would do if we didn’t have food or jobs — they join an organization they think will do something about it.”

It is exactly that thinking that needs to come into play as governments try to find a way to combat terrorism, Negrón-Gonzales says.

“Even if the U.S. and its allies launched an effective, successful attack, we would still need to dismantle the jihadist network. Even if ISIS was militarily defeated in Syria, there are already terrorist cells in Europe and the U.S. that can continue to exist,” Negrón-Gonzales says.

To stress that point with her students, Negrón-Gonzales uses counterterrorism exercises that provide a multipronged approach to the problem to help them understand that military action alone isn’t the answer.

“A solution has to entail a lot more. It needs to include working with a variety of communities, targeting at-risk youth before they become radicalized, working with youth in prisons — we know that some of the French jihadists had spent time in jail — all that needs to be dealt with,” Negrón-Gonzales says. “Even people whose jobs are to keep America safe 24 hours a day know it will take more than just military action.”

Ramsay says using a human security approach that focuses on providing people with food security and environmental security could help make extremist groups less compelling to potential recruits.

“If more people had the ability to feed their family, to work, to be engaged, to live a life, more people would see the bad guys as less relevant. They wouldn’t need to join those groups because they’d have their own structure,” he says, adding, “We can’t make terrorism disappear. There’s no victory lap here.”

And while it appears that the timing of Tuesday's deadly explosions could be tied to the recent arrest of Salah Abdeslam, a prime suspect in the November terrorist attacks in Paris, Ramsay says it also could have been unrelated.

“I would guess there are a variety of groups in world that have a plan in their back pocket, and when it suits them to strike, they do,” Ramsay says. “It could have been in their back pocket, and they were looking for a reason. Or it could be someone woke up Tuesday and said ‘today’s the day.’”

-

Written By:

Jody Record ’95 | Communications and Public Affairs | jody.record@unh.edu