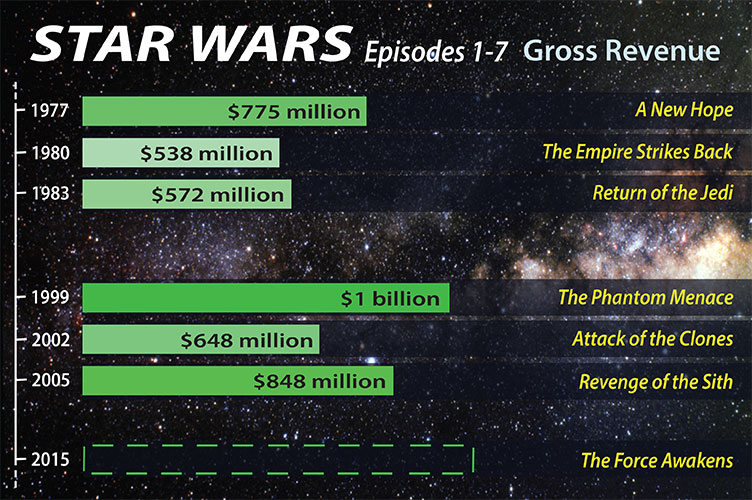

“The Force. It’s calling to you. Just let it in.” So ends the official trailer for “Star Wars Episode VII: The Force Awakens,” and countless moviegoers are planning to do just that when the film opens this Friday.

“The Force Awakens” may be one of the most anticipated films since “Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace” premiered in 1999. What is it about this tale that takes place in “a galaxy far, far away” that is so compelling? What first captured the public’s attention in packed movie houses in 1977 that keeps those who stared up at the Death Star and saw the Millennium Falcon crossing the screen for the first time all those decades ago coming back for movie after movie? And why does the “Star Wars” saga pull in new generations of loyal fans with each new chapter?

Perhaps it is the mythological quality of the story — elements that have made epics like “The Odyssey” and “The Iliad” household names for thousands of years. But, as R. Scott Smith explains, “Star Wars” also encompasses elements that you won’t find in traditional Greek or Roman mythology.

Smith is not only a classics professor and director of UNH’s Rome program but also an avid “Star Wars” fan. Sitting in his office in Murkland on a warmer-than-usual December afternoon, Smith talks about seeing “Star Wars” back in 1977 and being awed by the special effects and the story as a child.

Smith smiles, discussing where the “Star Wars” saga embodies some of the elements of myth — the quest, the hero, the adventure — and how the hero has changed in modern stories.

Scholarship indicates there are some 60 elements in the quests of classic heroes like Heracles, Jason and Achilles, Smith explains, including the hero’s unusual birth and exceptional strength. In modern stories, however, “the hero myth has evolved to include challenges at a young age that were not part of Greek mythology.” Think Anakin Skywalker, born into slavery, or the young Harry Potter living in a cupboard under his aunt’s staircase. Such elements were not found in classic myths. “Heroes were always larger than life in Greek mythology; they were not disadvantaged or accidental heroes,” Smith says.

Another difference is that unlike the fight against “the dark side” in the “Star Wars” saga, “Greek myths don’t have the battle of good versus evil,” he explains. “Heroes are not fighting for mankind like in a Spaghetti Western. There might be battles of Greeks against ‘others,’ but it is not about good versus bad. This has come more from Christian tradition.” He illustrates by describing a scene from “The Iliad” where Achilles describes the Jars of Zeus to Priam, showing the arbitrary nature of what the gods throw at humanity. It is never all good or all bad.

In Greek mythology, the gods are always present, Smith explains, choosing sides and often fighting alongside the humans in conflicts like the Trojan War. In “Star Wars,” meanwhile, the Force is always present. “The Force sounds a lot like divine support for the Greeks,” Smith says.

Myth is moldable, he notes. “It can be changed in sometimes small and subtle ways by the culture using it.“

In his study of myth, Smith’s focus is not just on the origins. He examines the question: “Why is it inherently compelling?” Regardless of when they occur in time and where on Earth — or in space — they draw the reader, listener or viewer in.

“People who are larger than life really are compelling. Adventure is compelling.”Traditional Greek heroes also have tremendous flaws, Smith notes. The qualities that made them heroes — such as exceptional physical strength — did not mean they were morally superior. In that way, Smith muses, Darth Vader might be more in keeping with a traditional Greek hero than his son Luke: He has exceptional strength and ability, an unusual birth and a tragic flaw.

“People who are larger than life really are compelling. Adventure is compelling.”

Just as Heracles journeys in “The Odyssey,” Luke journeys from Tatooine — a strange desert planet filled with unexpected creatures — into space. The audience is “taken out into a new world where you get to see things that make you think in other ways,” Smith adds.

Part of what compels us with films like “Star Wars” is the sense that “there’s going to be more,” Smith adds, noting the same might be said of performances of myths in ancient Greece, where each telling would include an evolution.

In many ways, Smith suggests, movies are today’s epics. Just as myths were recounted as plays or via storytelling, word-of-mouth fuels the excitement around these modern sagas, with lines outside some cinemas beginning days in advance of Friday’s premiere.

“Myth was a communal experience, just like movies today,” Smith explains. Myths “would have been something that brought people together.”

-

Written By:

Jennifer Saunders | Communications and Public Affairs | jennifer.saunders@unh.edu | 603-862-3585