As trends point toward increasing coastal pollution — and with the value of coastal recreation estimated at $400 million in New Hampshire and Maine alone — beach closures represent a significant sustainability problem with complex and interacting economic, social and environmental dimensions.

The seaside community of York, Maine, has been committed to creating a science-based water quality advisory program, and UNH researchers are analyzing water quality and interviewing local businesses to provide a model for sustainability.

“York is a great area to focus on because it’s very indicative of many of our Maine beaches,” explains Keri Kaczor of the Maine Healthy Beaches Program. “Getting more data to develop models can take management to the next level.”

Testing the Water

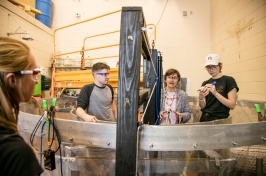

Earlier this fall, UNH associate professor in natural resources and marine science Steve Jones and Derek Rothenheber, a graduate student who has been collecting water samples at two of York’s public beaches every week since May, were at Short Sands Beach taking part in the environmental science equivalent of a "CSI" case. As Jones and Rothenheber collected small handfuls of seaweed around a storm drain, they discussed DNA. Ignoring the flies, Jones dug down to get samples from the bottom layer as Rothenheber lowered a device into the drain to fill vials with water before wading out into the ocean for further sampling.

Rothenheber has adapted methodologies that allow the team to use DNA analysis to sleuth out pollution sources—such as feces from seagulls, dogs or humans. He is also developing an added layer to this process that will quantify the data gathered.

|

“This will enable us to see whether the bacteria that occur naturally in the environment and the other sources of contamination like leaky septic tanks are increasing together or independently,” says Jones. “And that has management implications. We don’t propose to put diapers on birds, but we want to figure out practical ways to manage water quality. If the analysis suggests it’s from a human source, this would imply that the town may need to do some type of infrastructure modification or possibly fix the leaks.”

“We’ve engaged professor Jones to do studies here before and to learn more about what we can do,” says York Parks and Recreation’s Mike Sullivan, adding, “we don’t have any different water quality issues than any other beach on the Seacoast; we’re just very actively and proactively trying to address it.”

Making Connections

“Everyone’s interested in what causes a town to have to post an advisory — and what can be done to prevent that,” Jones explains. “No one wants to risk getting an infectious disease by swimming in contaminated water. Whether the source of the problem is with human contamination or something else, you’re going to have to figure out a solution to deal with it.”

UNH associate professor of sociology Tom Safford and his team of research assistants, meanwhile, have been canvassing the beach community.

“We are really interested in understanding more about the businesses that are likely to be affected by a beach closure or any kind of issues with water quality,” Safford says.

His team worked to determine how the business community perceives water quality, and preliminary findings show opportunities for strengthening the connections.

“We want to get the scientific data on this so we can help towns to manage these issues effectively.”“I think that’s our contribution — to help identify those links, or missing opportunities in terms of communication, and where improvements in the process might help keep visitors to York’s beaches safe while maintaining a vibrant beach economy,” Safford says.

Charlotte Thompson, an undergraduate sociology major, explains, “People have very different conceptions about what water quality means, about the sources of pollution and the risks. And it was in ways that we didn’t expect. For example, when we asked about beach management, many thought of seaweed or trash, so they would see these visual cues, but it didn’t appear there was an understanding of the bacterial aspects of water quality.”

Jones has also heard people say seaweed itself is a source of the bacteria.

“And it’s not true. It’s when the seaweed gets into a situation … where it sits out of the water, moist and covered, and starts to cook out in the sun. The few bacteria that are there all of a sudden start to proliferate,” he explains, adding, “We want to get the scientific data on this so we can help towns to manage these issues effectively.”

Knowledge to Action

The case study in York is connected to a larger regional project, the New England Sustainability Consortium, funded by the National Science Foundation’s EPSCoR or Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research programs.

Isaac Leslie, a sociology graduate student working with Safford and Thompson, notes the connections with other scientists inherent in this work, including “integrating and collaborating with quantitative scientists at the University of Southern Maine … as well as with the natural science folks like Jones and Rothenheber who are doing the bacterial analysis. It’s interesting how each slice of our focuses and methods and disciplines reflect on the other and sheds a new piece of light on the other.”

The team plans to share the results in either one comprehensive report or through a series of briefs to build on the collaborations forged through this research and put actionable information into the hands of those who can use it. To receive electronic versions of the reports, sign up with NH EPSCoR’s program here and select “Safe Beaches and Shellfish Project.”

-

Written By:

Evelyn Jones | NH EPSCoR