PAYLOAD PAYOFF

Just before 11 p.m. on March 12, as dozens of UNH faculty, students and administrators watched, a decade of UNH research blasted into space from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida. UNH scientists, led by professor of physics Roy Torbert of the Space Science Center at UNH’s Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans and Space, coordinated and built nearly half the instruments on board the four identical satellites of the Magnetospheric Multiscale Mission, or MMS. MMS will fly into the region surrounding the Earth’s magnetic fields to learn more about the little-understood phenomenon called magnetic reconnection. It’s behind what Torbert calls “big energetic events in astrophysics,” including those that can wreak havoc on telecommunications networks, GPS navigation and electrical power grids. Want to know more about the mission? Check out NASA’s web page on the project at www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/mms

The Big Burp Theory

Geologists drill for climate clues

About 55 million years ago, the Earth burped up a massive release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere — an amount equivalent to burning all the petroleum and other fossil fuels that exist today — and got hotter by 9 to 15 degrees Fahrenheit.

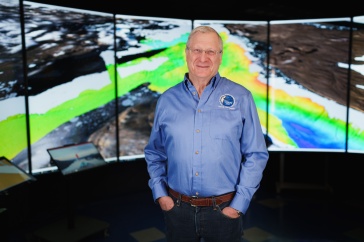

For decades, UNH geology professor Will Clyde and other scientists have peered into that unique moment in our Earth’s history — the so-called Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum (PETM) — and probed the implications it could have for current climate change by studying a 100-mile-wide semiarid corner of Wyoming called the Bighorn Basin, where sediment records and animal and plant fossils from the PETM are preserved in stratified rock outcroppings.

For the past five years, Clyde has led a team of scientists from 18 institu-tions in a pioneering National Science Foundation-funded study that researchers hope will provide more clues to that huge release of carbon and the associated warming event. To get an even closer look at the geological record, earlier this year, the $1.4 million Bighorn Basin Coring Project drilled six 2½ -inch diameter cores about 150 meters into the sediment.

“These rocks at the surface are always affected by weathering,” says Clyde, “so we decided we should have pristine rock from coring.”

The drilling was a success, producing six samples that were shipped to an international core depository at the University of Bremen in Germany. Even more successful, however, is what those samples have revealed.

“Because we can study the core in such better detail than the outcrop, we found this pretty large, very short burp before the main PETM,” says Clyde, describing escalating atmospheric carbon levels associated with a smaller period of warming that preceded the PETM.

The findings indicate that the PETM looks more like modern human-caused global warming than previously thought; less likely the result of a unique event like a meteor strike than a natural part of the Earth’s carbon cycle. As analysis of the Bighorn Basin samples continues, scientists are gaining more insight into what triggered the PETM — a mystery that unnerves Clyde and his colleagues.

“This carbon release is a big part of the carbon cycle that affected the climate system, and we still don’t understand what caused it,” says Clyde. “What we do understand better and better are the effects. It is very similar to what we see happening today because of modern CO2 release from the burning of fossil fuels.”

Chemical Conundrum

Could your couch be making you fat?

When it comes to maintaining a healthy weight, conventional wisdom suggests that hours on the couch with a bowl of ice cream will, for most of us, pack on the pounds. For the last decade, however, Gale Carey has been wondering whether it’s chemicals in the couch that might contribute to weight gain.

A professor of nutrition, Carey explores the connection between obesity and environmental chemicals. Her latest research has linked chemical flame retardants — ubiquitous in carpets, upholstered furniture and electronics — to insulin insensitivity and metabolic problems, both hallmarks of obesity.

“We aren’t trying to say flame retardants are the cause of obesity, but they could be a contributor,” says Carey. “Diet and exercise are the two biggies, but there’s this third component that we haven’t, until recently, considered that could be contributing.”

Carey initially approached research into the class of chemical flame retardants called polybrominated diphenyl ethers, or PBDEs, with a scientist’s skepticism. But when she and her colleagues exposed rats to PBDEs during growth to see how the chemicals affected fat storage and production, they found something surprising: the fat cells from the rats that were given the flame retardants behaved metabolically like they were taken from rats that were overweight.

More recently, Carey has looked at the effect of PBDEs on an enzyme called phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, or PEPCK, which manages fat and sugar metabolism in the liver. “The liver gets the first pass of all the good, the bad and the ugly of what we’ve consumed,” she says, making it a great study site for roots of obesity.

Working with master’s student Kylie Cowens and funding from UNH’s N.H. Agricultural Experiment Station, Carey found that in rats exposed to PBDEs, both PEPCK activity and the liver’s ability to bind fatty acids were suppressed by nearly 50 percent — biochemical changes that could lead to insulin resistance.

While Carey’s focus remains fixed on the science of chemical flame retardants, she goes beyond the lab to explore the public health and policy implications of environmental chemicals like PBDEs, now dubbed “obesogens” for their link to human obesity.

Along with UNH seniors Mason Adams and Kasey Cushing, Carey is currently working on a study that’s measuring flame retardants in dorm rooms at UNH. Spearheaded by Silent Spring Institute, a nonprofit research group from Massachusetts, the study aims to bring environmental chemicals under the umbrella of the campus sustainability movement, raising awareness among environmentally active college students that could, she says, “potentially change campus purchasing policies and have a domino effect across the country.

“There are 100,000 synthetic chemicals in our environment. Hundreds of these get into our bodies and can affect our health. By refusing to buy products containing these chemicals, and voicing their opinion to Congress, people can affect change. Is this the environment — and the health — we want for our children, and future generations?”

Originally published in UNH Magazine—Spring/Summer 2015 Issue

-

Written By:

Beth Potier | UNH Marketing | beth.potier@unh.edu | 2-1566