It was only a generation ago that Manchester residents joked about needing a passport to visit the French-Canadian neighborhoods on the city’s west side. Cross the Merrimack River and you might hear conversations in French while getting poutine at a neighborhood restaurant. For decades, it’s what passed for diversity in a city with a homogenous racial make-up. Things changed quickly, though: Since 1990, Manchester’s demographics have shifted from a population that was more than 95 percent non-Hispanic white people to less than 80 percent. Immigrants and refugees from South America, Africa and Asia have made Manchester increasingly diverse, and nowhere are the changes more visible than in the city’s neighborhoods.

But what happens when a city experiences a sudden shift in diversity? Does the change in demographics reduce racial inequality and increase tolerance? And what happens to the city’s neighborhoods, civic organizations and schools? Those are some of the questions sociology Ph.D. candidate Justin Young is hoping to answer in his dissertation. He received a 2014-2015 Dissertation Year Fellowship from UNH, with which he’s been able to continue his research.

Prior sociological research has focused on the quantity of relationships between residents in more and less diverse neighborhoods. Young, a research assistant at the Carsey School of Public Policy, focused on how those relationships, known as “social capital,” are cultivated and nurtured, and how they benefit both groups.

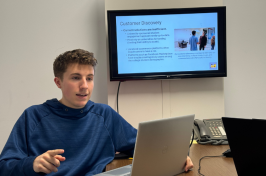

|

| Justin Young |

“Justin reads widely and he’s ambitious and pushes himself to keep digging, either for more data or for a conceptual understanding of some of the puzzles he’s trying to disentangle,” says professor of sociology Michele Dillon, Young’s dissertation chair and advisor. His research, she says, “opens up more kinds of nuanced analysis of racially and ethnically diverse communities.”

Young spent the summer of 2012 wandering through four of Manchester’s neighborhoods and collecting data. He’d park his car and walk around, taking notes on the buildings, shops, restaurants and schools he found. He spoke with residents at their homes and in community meetings. Sometimes, he’d simply sit on a park bench and watch a neighborhood’s ebb and flow.

“Somebody would see me with a notebook and become interested in what I was doing and just start talking about the neighborhood,” Young says.

The picture of those neighborhoods is complicated. Though a neighborhood might be racially diverse, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the relationships between white and non-white residents are strong. Diverse neighborhoods help increase those connections and can improve race relations, but that only goes so far, Young says.

“One of the most striking things is that residential integration is necessary for racial equality, but it’s not a cure-all for racial inequality,” he says. “Just because people live in a neighborhood that is becoming more racially diverse doesn’t mean they have racially diverse social networks.”

He found that white residents living in less diverse neighborhoods, or on the border of a more racially diverse neighborhood, were more likely to have an indifferent or negative view of diversity. Some saw increasing diversity as “draining the city’s resources,” or they thought immigrants and refugees weren’t taking steps to become integrated, and many of those residents were more likely to be less connected to their neighborhoods.

But, according to Young, both non-white and white residents living in more racially integrated neighborhoods seemed to embrace the diversity.

“Some people really valued living in a neighborhood partly because it’s so racially and ethnically diverse, and they want to be part of that because that’s the future of Manchester and the future of the nation,” he says.

And those attitudes shape who gets involved in schools, civic groups, churches and other networks that are vital to cultivating bonds between diverse populations and increasing a group’s social capital. If white residents aren’t taking steps to include people of color in those networks, minority populations are less likely to get involved, even in diverse neighborhoods.

Young saw the impact first-hand. He spoke with a group of Hispanic parents and asked them what problems in their neighborhood and local school they’d like to see fixed. “It was being attached to a parent-teacher group that helped them say, ‘This is one of the issues our school is facing, let’s go to the next Board of Alderman meeting to talk about it,’” he says.

Income inequality also shapes attitudes about diversity and affects which groups get involved in their neighborhoods, according to Young. Diverse neighborhoods are more likely to be economically disadvantaged, and the gaps between the city’s non-Hispanic white population and minority groups are most clear when looking at income, education levels and home ownership.

“When you observe diversity in a neighborhood firsthand, you can’t escape the fact that inequality is playing a major role,” Young said.

In fact, he believes that income inequality may be the biggest stumbling block when it comes to improving race relations. Integrated, diverse neighborhoods help, but according to Young, more economic parity between Manchester’s white residents and the city’s minority populations will lead to more equal social capital and civic involvement between the two groups.

Manchester and other cities in the northeast are only going to grow more diverse, says Young. “Even if immigration stopped entirely, the city would still become diverse simply because of demographics.”

That change is reflected everywhere, from the city’s schools to its churches, where a service in English might be followed by a service in Spanish and then one in Arabic. It’s not passports that Manchester residents need to appreciate the city’s diversifying neighborhoods — just a willingness to be more inclusive and embrace change.

Originally published by:

The College Letter, the newsletter of the UNH College of Liberal Arts

Written by Larry Clow '12G

-

Written By:

Larry Clow '12G | UNH Cooperative Extension