Remember summer? While you pull on your winter boots and zip up your parka, allow us to take you back to the dog days, when Katherine Cart ’15 was in Walpole, Maine, studying some of the smallest organisms in the Gulf of Maine’s tidal waters. Her research project continues this fall and will culminate in a spring semester presentation at the 2015 Undergraduate Research Conference in April.

Thousands of silversides are schooling around the dock of the University of Maine’s Darling Marine Center on the Damariscotta River in Walpole. A jellyfish floats by. The sun is casting a yellow glow over the evergreens along the shore. It’s just where you want to be on a beautiful summer day—unless you’re a mysid, that is.

Mysids are shrimp-like crustaceans found in estuaries and rivers. They eat lots of things and lots of things eat them, including the silversides just below the surface. It’s noon, and if we threw a net into the water, we probably wouldn’t pull up any mysids. Here in the Damariscotta, where the water is relatively clear, during the day they hang out at the bottom, near the sediment, where the turbidity makes them less likely to be spotted by a predator. In the dark of night, though, mysids are on the move, swimming up through the water column to forage near the surface. It’s an arduous ascent that takes them out of their protected zone, with only the dark of night keeping them from becoming a midnight snack. But it’s a journey that rewards—near the surface they’ll feed upon highly nutritious zooplankton.

Meet Kate Cart

Kate Cart '15 knows about arduous ascents. She has summited Mount Washington, Mount Lafayette, Mount Katahdin—even the peaks of Peru. As a solo hiker and distance runner, long journeys and their big payoffs are familiar to this biology major.

A senior at UNH, Cart spent the summer delving into the world of mysids—studying where they hang out, what they eat and under what conditions, and what eats them. She is one of three researchers exploring the habits and behaviors of mysids under the guidance of Rachel Lasley-Rasher, a post-doctoral fellow at the Darling facility.

“Mysids play an integral part of the estuarine food webs in the Gulf of Maine and many temperate estuarine ecosystems around the world,” says Lasley-Rasher. At a centimeter, their intermediate size makes them a feasible feast for small fish and big fish. That’s a big deal in estuaries, which serve as nursery habitat for fish like Atlantic salmon, alewives, smelt, flounder and herring—species that count mysids as a key part of their diets.

Maine native Cart has spent the last two summers at Darling working with Lasley-Rasher. In 2013, she prepared water samples for chemical analysis. This past summer, she used a Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship grant from the UNH Hamel Center for Undergraduate Research to find out how turbidity levels affect mysids’ foraging behavior.

“Turbidity is a very important topic in coastal and estuarine science because it is changing, and we need to understand what affect changing turbidity has on the basic functions of these animals,” says Lasley-Rasher. She points to stronger storms, longer growing seasons and increased coastal development as three of the factors causing turbidity changes. Knowing more about how turbidity affects mysids will help researchers understand how it affects overall estuary health.

The Rigors of Research

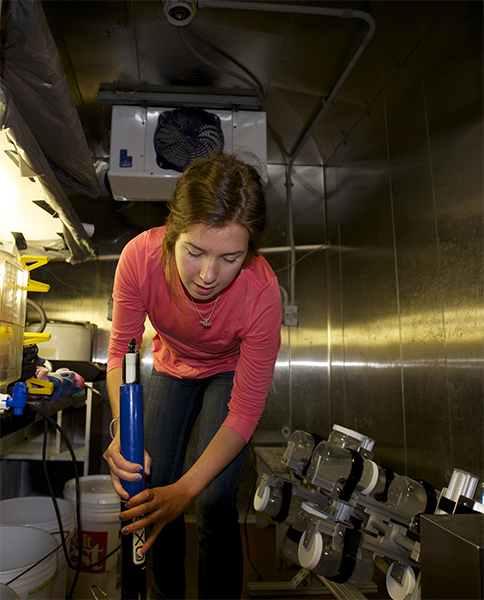

Over the summer, Cart ran experiments to determine mysids’ feeding levels in varying degrees of turbidity. In a cold room at the Darling Lab, she set up a plankton wheel to mimic the natural environment of mysids—no walls, constant motion, and varying levels of clarity. She collected mysids and their prey species—tiny crustaceans called copepods—from the Damariscotta then added one mysid and 20 copepods to each jar on the plankton wheel. After a few hours, she removed the animals, keeping the mysids separate and counting the remaining copepods to see how many were devoured in the differing levels of turbidity.

“Just to figure out how turbidity affects feeding, we had to first figure out how long to run the experiments, which animals to use for prey and how to make and maintain turbidity treatments,” Cart explains.

More About Kate

Longest solo run = 34 miles

Favorite hike in Maine = Tumbledown

Favorite hike in the Whites = Lafayette

Little known fact = Across her shoulders, Kate has a tattoo of the sun setting behind New Hampshire's Presidential Range

In research, roadblocks are common, and the turbidity measurement proved to be one of Cart’s first. The tool she used emits a light and then measures the amount of light captured at a 90-degree angle to determine how much light was scattered by particles in the water. Because Cart was measuring into a clear jar in a lit room, the measurements were becoming distorted. “I had to really think about how light creep was causing the distortion,” she says. Cart figured out that she would get a more accurate measurement of turbidity if she put a towel around the jar to prevent light from coming in on the sides. This simple trick, Lasley-Rasher says, gave her more accurate, repeatable results.

“This is the work of a research scientist,” says Lasley-Rasher. “There are the methods, but then there are methods—tricks of the trade, like this one.”

The Reward: Results

Cart says she applied for the SURF grant because she wanted to go through all stages of the scientific process, an endeavor she describes as satisfying. “It’s what I’d rather be doing—something that gets results.”

The results she ended up getting were unexpected. The strain of mysids collected from the more turbid area near the shore fed at about the same rate regardless of turbidity, while the feeding rate of mysids collected from the less turbid water off the dock showed extreme feeding changes with changes in turbidity. “We didn’t expect to see that at all,” says Cart.

This fall, she’s conducting gut analyses using images of mysids collected in another Maine river—the Penobscot. “The mysids are so small and translucent you can see if their gut is full or not. So I’m basically saying ‘full,’ ‘not full,’ and then seeing which area they came from,” she explains. She’ll finish this work during winter break and then begin the writing process. Her research will culminate in a presentation at the 2015 UNH Undergraduate Research Conference in April.

Cart says it has been interesting to realize that not everything is known. “I was expecting there to be more information on this topic handy, but there are really just gaps in knowledge everywhere, which is cool. The idea that everything is known is depressing. There are more frontiers to expand upon.”

-

Written By:

Tracey Bentley | Communications and Public Affairs