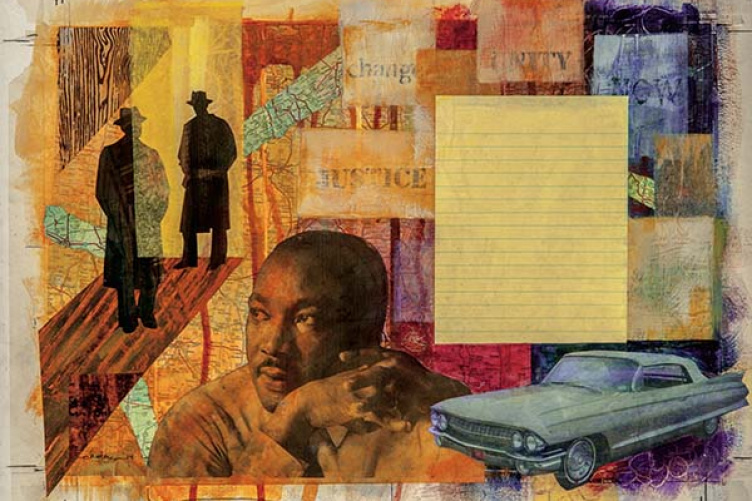

Illustration: Ekua Holmes

Thump, thump, thump. The sound wove harmlessly through my dreams until a loud voice roused me: "Mr. Fernandez, open this door!" I sat up as my brain kept fumbling. Where was I?

The answer came in pieces. YMCA. Montgomery, Alabama. Spring 1959. Junior year at UNH. Still, the summons made no sense. I knew no one in Montgomery, so who could be knocking?

At the door, two men in suits barked names I quickly forgot while flashing badges I'd always remember. We're from the FBI, they said, and we have questions. Who are you? Where do you come from? Why are you in Montgomery?

The more questions they asked, the more nervous I grew. Though I'd never been arrested, I had no doubt this was an interrogation. Finally one agent asked the big one: "Are you a member of the Communist Party, do you work for the NAACP, or do you write for The New York Times?"

I'd soon learn that these three groups were inextricably linked in the minds of many Southerners who opposed integration. That night, however, all I could say was no. Finally, the agents turned to leave. "I wouldn't stay in Montgomery very long," one of them warned.

My heart raced as I crawled back into bed. I was 24 years old, an Army veteran working on a research paper for a course at UNH. I'd attended a few small civil rights rallies in New Hampshire and a Yale conference at which liberal lawyer Allard Lowenstein described the 1950s South as a police state. Really? In America? I was skeptical.

For my government course, I'd decided to explore the aftermath of the 1956 Montgomery bus boycott. But weeks of research had convinced me that working from Durham, I'd never fully understand. So with that blend of optimism and naivete reserved for the young, I used letters and phone calls to arrange interviews with a dozen key civil rights figures. Then I started hitchhiking to Alabama and Atlanta for spring break.

Even before the FBI banged on my door, the trip had become a series of wake-up calls. Like a study-abroad program in my own country, it upended my assumptions and pushed me toward new ways of thinking. My teachers for this on-the-road education ranged from passing drivers to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

First came the well-dressed gentleman in the gray Cadillac who picked me up outside Washington, D.C. He had a phone in his car—in 1959! After chatting pleasantly, he suddenly began throwing around the N-word, talking about how "they" wanted to "use our libraries, swim in our pools, and get in bed with our women."

For thirty minutes, I sat in stunned silence as he ranted. Only when he let me out in front of a diner in southern Virginia was I able to breathe again. I wished I could have told him off. But closed into a car on unfamiliar roads with a hostile stranger, I thought it wise to keep quiet and stay safe.

My next ride was a long one, from Danville, Va., almost to Birmingham in a 18-wheel cotton truck empty of its load. When the friendly driver mentioned that he came from Pulaski, Tenn., I winced, knowing Pulaski was the birthplace of the Ku Klux Klan.

Then the trucker surprised me. Paying for two school systems, one for whites and one for "coloreds," was a waste of money, he said. "Hell, I don't care if they go to school with my daughters as long as they don't take our jobs."

At 4 a.m. on a pitch-black rural road somewhere in northern Alabama, I stepped down from that truck wondering whether I understood a single thing about race relations. In class it had been easy to believe the theories of sociologist Gunnar Myrdal, who said that among opponents of integration, the wealthy fear job loss while the poor fear intermarriage. Out here on the road, the drivers of a Caddy and a 18-wheeler had instantly stood that idea on its head.

“What You Believe Is What You Should Do”

Dick Fernandez ’60 has spent his life working for social justice. He became a prominent antiwar activist during the Vietnam period. Over the years he has directed three advocacy groups and served on the boards of many nonprofits, including several with which he remains active. A widower with three sons and eight grandchildren, he lives in Philadelphia and often spends time at Squam Lake in New Hampshire. Fernandez talked with writer Jane Harrigan about the road he’s taken since leaving UNH—including stops in Paris, Hanoi, and a North Carolina jail.

Q: You started at UNH twice. What’s the story?

I was president of my freshman class (in 1953) and played on the basketball team, and I had a lot of fun being involved in campus activities. By the time my grades came in, I had sure proof that I had enjoyed my social life.

The dean said I could either go on probation and pull my grades up—but not play basketball—or I could drop out, take a couple courses close to home, and reapply in the fall. It took me about 10 seconds to say, “I think I’ll leave.” That was me saying out loud something deep inside that I’d been unaware of: I really didn’t know what I was doing at UNH.

A couple weeks later, on the prompting of a high school buddy, I volunteered for the draft, a two-year commitment. My parents got upset; my friends couldn’t understand. Only my pastor said, “Well, you might enjoy two years in the service.” What he meant was, “You might even grow up.”

Q: So you were in the Army, mostly in Japan, and came back wanting to be a minister?

In the Army I became a very conservative evangelical Christian. When I returned to Durham, I rented a room from G.R. Johnson, a history professor who had been an evangelical earlier in his life and had moved away from it. He opened up a whole new world of religious thinking and social responsibility to me. By the time I left UNH, I knew that whatever my ministry was, I wanted to continue to be engaged in issues of peace and justice.

Q: You’ve worked in multiple places on multiple issues. Tell us about some of them.

My friend and teacher Harvey Cox and I and some others were asked by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to go down and support the protests in Williamston, N.C., to help the local African American residents. That became a 2½-year commitment. I spent time in jail, and my car was hit by a Molotov cocktail—with me in it. Eventually our efforts led to integration of the local library and swimming pool.

My first job after seminary was director of the Christian Association of the University of Pennsylvania, a group of nine campus ministries. We got involved in avant-garde theater and draft counseling, and in 1965 we held a silent vigil about Vietnam outside the college president’s house. Our small band of protesters got beaten up by some other students, and it made the papers. Six of us resigned when the board was being unreasonable, about that and other things.

Q: After Penn you were often in the news for your activities in the Vietnam protest movement. How did that come about?

My friend William Sloane Coffin, chaplain at Yale, helped me land a job with a new group, Clergy and Laity Concerned. We grew as the war expanded. One aspect was my involvement with the Committee of Liaison in New York, which provided letter exchanges between POWs and their families. On two trips, I carried hundreds of letters to Paris and Hanoi from families, and returned with several hundred letters for the families from the POWs. As we carried on what I’d describe as a lovers’ quarrel with our leaders about American policy in Vietnam, I found the work at once painful and important.

Q: Later you spent three years trying to help Ohio steelworkers buy a closed mill, and then 21 years running the Northwest Interfaith Movement in Philadelphia. You’ve also worked on early-childhood education, lifetime care for seniors, and many other issues. What thread connects all those efforts?

Going back to the Army and the friends I made through the Bible study group, the way they lived their lives, I realized that what you believe, if you have any integrity, is what you should do. I would not have been in the peace movement if I hadn’t first been a fundamentalist. You have to do what you say you believe. Prayers need feet; faith needs traction.

Through my anti-war work with Clergy Concerned, I realized that it’s often easier to work for social justice along interfaith lines than to depend solely on one congregation. That’s particularly true if you’re doing advocacy work. There are many more people willing to provide services to the poor and the marginalized than there are people willing to advocate for better public policies. It’s easier to give a loaf of bread than confront a politician. And a loaf of bread is good—but if we don’t change policy, you’re going to be handing out bread for the rest of your life.

I was getting smarter—sort of. When the desk clerk at the Montgomery YMCA asked too many questions as I checked in, I said only that I was "doing research." Then I blew it by asking around town for help finding Clifford Durr, a white lawyer who took civil rights cases.

That night the FBI came calling. Nevertheless, I spent the next two days interviewing Alabama Gov. John Patterson, newspaper editor Grover Hall, and the Rev. Ralph Abernathy, one of the organizers of the bus boycott. As we shared sandwiches in his home, the blinds closed for security, Abernathy told me, "Protecting against hate all the time is no way to raise a family."

From Fred Gray, a black lawyer, I learned that movements have life cycles. The intense activity of the boycott had been replaced by a period of quiet reflection, he said, especially for people who had sacrificed for the cause. He believed that many whites would go to their graves still hating the "uppity Negroes" who had forced integration.

But my biggest lesson from Gray ran along more practical lines. I'd been waiting for some money my parents had wired. Each day the YMCA clerk said he hadn't seen it, and he said the same that evening when I came in from my interviews. One of the FBI agents who'd come to my door was standing at the desk, so I quickly headed to my room.

Halfway up the stairs I spotted a Western Union envelope lying on a step. It had been opened. Inside was my $75 money order. I went to bed feeling scared but still planning to do more interviews in Montgomery, stay one more night, and then leave for Atlanta for my appointment with Dr. King.

When I told Fred Gray the next morning what had been happening at the Y, he calmly suggested it might be best to leave right away. He didn't have to tell me twice; I got on the bus.

I checked into the Atlanta YMCA and, what do you know, at midnight heard a knock on my door. Two police officers, sounding apologetic, said the FBI had called them from Montgomery and they were required to follow up. Come with us, they said, and we'll show you something interesting. Somehow I didn't feel threatened, even in the cruiser.

In the cafeteria of the main police station, they shared food and urged me to look around. Black and white officers were sitting together at nearby tables, talking and laughing. "Atlanta is a lot different from Montgomery, and we're proud of it," one of the officers said.

As I wandered the city the next morning, I saw more evidence of integration, though I did notice that many black passengers still sat in the back of the bus. I asked Dr. King about that later in the day, when we met in his office at the Ebenezer Baptist Church, where his father was pastor.

"Change for any of us comes slowly" was his response. Words of wisdom, definitely. But as my teacher that day, Dr. King instructed less through what he said than how he said it. This champion of social justice, whose face I'd seen on the cover of Time, asked about my life and acted as if he had no commitment more important than talking to a college student who nervously clutched a yellow legal pad.

Curiosity and inclusiveness, I learned, characterized his leadership. When questioned, he acknowledged the personal cost of his role in the movement. But he rarely used the word "I"; far more common were "we" and "us."

At one point as we talked, I offhandedly referred to opponents of civil rights as "rednecks." Dr. King let the conversation continue awhile before quietly challenging me. "Dick, when we use words like redneck, that's a way of objectifying the other person or group. We cut off the possibility of conversation with them, of eventually winning them to our side."

That simple word "we" transformed his comment from criticism to a guide for my life and eventual ministry. I would encounter Dr. King several more times—before his 1967 speech at Riverside Church in New York, condemning the Vietnam war, and later when he became co-chair of an organization I directed.

But my enduring image of him comes from our time in his office in Atlanta, just the two of us, at the end of that long-ago spring break when so much had happened. I hear his voice prodding me gently, and I remember his lesson, which I interpreted this way: Respect the people you're arguing with—because if you're ruthless about trying to get what you want, even victory won't wind up tasting very sweet. I've tried to live by those words ever since.

By the Rev. Richard Fernandez '60 with Jane Harrigan

Originally published in UNH Magazine—Winter 2014 Issue