The media hype around the Ebola virus in the U.S. may have subsided, but in the nursing profession, the Ebola threat in America is still very much a topic of discussion, debate and even protest in some parts of the country.

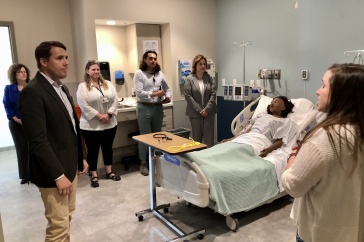

UNH nursing students have been studying infectious diseases in recent weeks, and talked recently about what they make of everything from Ebola-related quarantines for healthcare workers to their own fears of this and other deadly viruses.

"It's interesting that there's something like Ebola that the average American has slim to no chance of getting, but everyone is talking about it, and then the flu is something that everyone has a chance of getting, and no one is talking about it," says grad student Tory Bennett.

Many of them are taking part in clinical practicums at hospitals and schools throughout the state, and have had varying levels of experience with Ebola protocols. Some reported hearing about Ebola precautions, while others said that it was discussed in emergency departments, but not necessarily in the areas of the hospitals where they are working.

Assistant Professor of Nursing Rosemary Taylor has been using information about Ebola in both her graduate level and senior-level undergrad classes.

"This has given us a chance to talk not only about infectious diseases, but also talk about public response and public funding, and fear and blame... blaming healthcare professionals for misstepping, for example," says Taylor.

After a recent class discussion in Taylor's clinical nurse leadership program, grad student Bob Downard noted that "fear is a really powerful thing. This was unexpected, in that way it isn't like the flu, because no one was expecting Ebola," he says, adding that the way it's been sensationalized, the general public is really afraid of something that maybe they shouldn't be. But as a healthcare professional "it's certainly something to stay on top of."

Downard said if asked to volunteer to go to West Africa to treat Ebola patients, he might go — but not without doing some research first.

"I believe as a healthcare worker your own safety is your responsibility. I think if I was asked to volunteer like that, I'd look at the organization I was going with; I might be a bit more cautious about the Ebola outbreak there than here," he says.

For grad student Steven Jordan, volunteering would be a no-brainer.

"I would volunteer to go. I look at Doctors Without Borders and I think they're doing a great thing. You know the risks going in, but just because you know the risks and possibilities doesn't mean you would definitely contract the disease," he says.

Related: Click here to read about how two UNH alumni are on the forefront of the Ebola fight.

Taylor notes that her students are in real-world scenarios where these questions come up, and they help drive class discussion when sometimes it boils down to "What would you do if..." scenarios that may become reality for these students once they become full-time healthcare providers.

She says going into dangerous situations can be part of what it means to be a nurse. "Our job is to treat patients, and sometimes that involves having contact with patients who have infectious disease," says Taylor, who earned her doctoral degree in nursing last year from Northeastern, and has worked in the Emergency Department at UMass Memorial Medical Center in Worcester.

Still, she and some students say the answer to fight Ebola or other infectious diseases from spreading might not necessarily be to jump on a plane and head to a particular outbreak's site of origin.

As Bennett says, sometimes too many volunteers can make things worse.

Before going to Africa, she says, "I would weigh how helpful I could be against the possibility of being a vector and unknowingly bringing something back to this country," she says. "If I were an Ebola expert and knew everything there was to know and I thought I could make a real difference, then yes, that would be worth the risk of becoming contagious."

As a nursing student, senior Kayla Ross thinks the concerns domestically are hyped up by media coverage and some inaccurate information getting out, but that "globally, we are right to be concerned. Our next focus should be to contain it in other places and educate people in other countries," says Ross, whose nursing practicum is at a middle school in Haverhill, Mass.

For two of her undergraduate classmates working in schools, it seems more education is needed about how Ebola spreads and how prevalent it is.

Emily Schlachter '15 is working at a high school, and when a student returned from Nigeria a few weeks ago, some people worried he might be carrying the virus. Although it seemed overly precautious, said Schlachter, she and the school nurse took the student's temperature daily.

One benefit to the hype, says Caitlyn Cannone '15, is that facilities will be prepared with equipment and protocols for other diseases that might pose a more likely threat.

"It's not like Ebola is the only infectious disease out there. At least there will be some equipment available should there be some other kind of outbreak," she said.

Want To Know More?

To learn the latest about Ebola, including the history of this and other outbreaks, visit the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Ebola homepage.

-

Written By:

Michelle Morrissey ’97 | UNH Magazine | michelle.morrissey@unh.edu