One hundred years ago, Babe Ruth took the mound for the Boston Red Sox, an American steamship became the first vessel to pass through the Panama Canal, and a gentleman named M. Gale Eastman began visiting the farms of Sullivan County as New Hampshire’s first agricultural agent for the newly established Cooperative Extension system, setting the stage for a century-long partnership between the University of New Hampshire and New Hampshire residents.

In May of 1914, President Woodrow Wilson had signed the Smith-Lever Act, which called on states’ land-grant universities to bring practical education to the people where they worked and lived. That year, where most people worked and lived was on farms, and by 1917, UNH Cooperative Extension had agricultural agents on the ground in each of the state’s 10 counties—the first state in the nation to accomplish this. During farm visits, Eastman and his colleagues would find out what challenges farmers were facing and bring them new information and methods—some of which were generated at the state’s new Agricultural Experiment Station (NHAES)—to help improve their operations.

So, when NHAES researchers developed a promising new cultivation method, for example, Extension agents held demonstrations and training workshops for farmers in their counties. Or when apple scab threatened to wipe out the year’s harvest, Extension stepped in to help.

It’s a paradigm that persists today. “We’re in a different era, but agriculture is still very important to New Hampshire,” says UNH Cooperative Extension professor emeritus John Porter, whose great uncle, John Daniel Porter, was one of the Farm Bureau officials who appointed M. Gale Eastman a century ago. As the organization celebrates its centennial, Porter notes that the need for new information and constant improvement is as urgent now as it was a hundred years ago—if not more so.

At no time in recent years has that been more apparent to New Hampshire growers, perhaps, than in 2012 and 2013, when a seemingly insatiable insect bore down on their fruits and Extension answered their calls for help.

FLY, INTERRUPTED

Keith Marshall’s voice is still laced with dread as he describes the catastrophic loss facing Wilson Farms of Litchfield in the summer of 2012. “We got wiped out,” he says. “Eighty thousand dollars in raspberries and blackberries. We sprayed them, but never harvested them. We just let them drop to the ground.”

Marshall, Wilson Farms’ manager, was one of many growers who destroyed or opted not to harvest their soft berry crops that summer. Raspberries, blueberries, strawberries and other soft-skinned fruits had been assaulted by spotted wing drosophila, or SWD, an invasive fruit fly species native to China. Unlike most fruit flies, which target rotting fruit, the tiny SWD uses its serrated appendages to slice open still-ripening berries and lay its eggs inside. The result is a field of fruit that rots before harvest—or worse, makes it home with consumers unaware that their berries harbor the larvae of this formidable pest.

First discovered in the western United States in 2008, SWD had swept across the country with staggering speed. 2011’s Hurricane Irene accelerated the insect’s arrival in New Hampshire and created shady, damp spaces in downed trees and vines that were SWD’s preferred environment for procreation, setting the stage for the 2012 crisis.

Spotted wing drosophila is not the only bug keeping Extension specialists hopping. Alan Eaton, George Hamilton and their two insect scouts provide season-long, on-farm monitoring across the state for a number of unwanted visitors such as European corn borer, corn earworm, and fall armyworm. “We trap the moths with a pheromone lure that attracts the males. If we find a certain number, we know that the problem has crossed an economic threshold and we need to control it by spraying,” says Extension fruit and vegetable specialist Hamilton. The team also watches for squash vine borers on squash and pumpkin plants. If scouts find more than five borers on a plant, that’s a trigger to start treatment; for vine running plants like pumpkins, the threshold is 12. These strategies save money in crop value ($200,000 last year, Hamilton estimates) and in not applying pesticides when they’re not needed. “Last year farmers saved almost $40,000 just on spray materials,” Hamilton says.

“This was a record breaker in my career,” says UNH Cooperative Extension entomologist Alan Eaton, who estimated that New Hampshire growers lost $2 million in the berry crop that summer. To mount a counterattack against SWD, Eaton convened “a council of war,” bringing together Extension fruit and vegetable specialist George Hamilton, Extension agriculture field specialists and a small army of farmers to capture SWD, study it and estimate the extent of the infestation to develop individualized treatments for affected farms. Too little pesticide and an insect capable of producing 10 generations in a single summer—with each female laying up to 300 eggs per generation—would continue its infestation unchecked. Too much pesticide and the health of future crops would be at stake. The council’s SWD trap was simple and familiar to anyone who’s ever attended a summer picnic: a 16-ounce red Solo drink cup, baited with a shallow layer of vinegar, ethanol and grape juice. Extension field specialists, researchers and growers hung the cups among infested bushes, then counted the number of SWD in the sticky liquid in the trap to determine the proper treatment program. Two or three flies found in a trap every three days or so at the height of the season meant a modest infestation and a less aggressive application of pesticide. Ten or more flies signaled a bigger problem and the need for more spraying.

Once they had a handle on the extent of the problem, Extension specialists did what they do best: they took the information out to the communities where it was needed. They created a website, held gatherings in counties, hosted twilight meetings (a mainstay of Cooperative Extension outreach), and published a newsletter series. They visited dozens of farms regularly for reports from growers on new developments. “The great idea that has kept Cooperative Extension relevant for 100 years is taking our know-how out to the people who can’t afford the time to come to Durham,” says Ken La Valley, Extension’s interim dean and director. “Bringing information to the people is still how it works today.”

Cooperative Extension was born in the years following the Civil War, when America was struggling to heal and rebuild. The Morrill Act of 1862, a major investment in education and research, had made it possible for many states to establish land-grant universities with a mission to help farms rebuild as fathers and sons came home from war. The Act recognized farming as not only a science but a collection of sciences—animal husbandry, agronomy, hydrology, biology, botany, meteorology and climatology, to name a few—and a pursuit that required education and expertise to develop and improve.

But as families turned their attention to the soil, they had little time to travel to UNH for courses or workshops on agriculture, relying instead on knowledge and wisdom passed down through generations and shared among neighbors. “They had no time to risk experimenting with what had reasonably worked for them in the past,” says La Valley. “But the new information on farming techniques coming out of the land-grant universities wasn’t making its way to the people who needed it. Agricultural improvement came slowly, or not at all, and a lack of strategies for fighting pests and disease could ruin a farm and break a family.”

The Smith-Lever Act of 1914 addressed that problem by establishing a cadre of field agents, employees of the university, tasked with bringing practical information and new knowledge on agriculture to communities throughout the state, making the bounty of land-grant universities available to all of its residents. This new relationship—field agent and farmer working in partnership to increase productivity and realize more successful farms, families, and communities—became an American tradition. Today, Extension and the farming community work together to try new kinds of crops, experiment with alternative planting and harvesting patterns, test out new equipment and “grow” the next generation of farmers and citizens through the 4-H program. And they unite to tackle tough problems like SWD.

In 2013, armed with Extension intel on how to battle SWD, growers went to work—posting Solo cup traps, trimming or destroying SWD-favorite plants like pokeweed and glossy buckthorn, pruning bushes to eliminate shady spots and expose SWD to the pesticides, freezing and burying damaged fruit and covering crops with SWD-proof mesh netting. The results were stunning. In 2012, growers lost 25 percent of their soft berry crops. In 2013, that number dropped to five percent. A statewide loss of almost $2 million was reduced to about $200,000. Keith Marshall says Wilson Farm’s losses went from $80,000 to $1,500. “And that’s all because of Extension,” he says. “They educated us…nobody knew what to do. Everybody was freaked out, but Alan and George calmed us down, held meetings to give us guidance. Without their help, we’d still be having a lot of issues.”

The New Hampshire Agricultural Experiment Station (NHAES) is a hotbed of study for scientists from UNH Cooperative Extension and the UNH College of Life Sciences and Agriculture (COLSA). On a given day this summer, these and many other projects were underway:

Growing the growing season. Extension sustainable horticulture specialist Becky Sideman suggests that New Hampshire’s worst agriculture enemy is New Hampshire itself. “We have a very short growing season,” she says. “Our soils are variable, our climate is variable, going from zone 6B to 2A in the White Mountains with radically different production environments.” To prolong that season, Extension builds low- tech devices like high tunnels and low tunnels—small, tubular greenhouse-like environments—which can add more than a month to either end of the growing season for certain crops. “Our high tunnels at the Woodman Farm allow us to grow really hardy vegetables like spinach, kale and some overwintering crops like onions or carrots that we harvest very, very early in the spring,” Sideman says. She is also experimenting with potential crops like sprouting broccoli, which is planted in summer and harvested in February and March.

New life for greenhouses. Extension greenhouse and floriculture specialist Brian Krug is working to breathe new life into the greenhouse industry. Many greenhouses have closed as the costs to maintain them have overcome profitability. “One of the biggest expenses for greenhouses is heat,” Krug explains, noting that ornamental crops need a temperature somewhere between 65 and 70 degrees, 24 hours a day. Krug and his team are testing a new way to supply some of that heat. In the past, greenhouses have simply vented the extra heat that builds up inside while the sun is shining. “That heat is just lost,” says Krug. At the NHAES Woodman Farm greenhouse, the team installed heat pumps that capture and store solar heat in a hot water tank. At night, when the sun goes down and the greenhouse calls for warmth, the heat pumps turn on before the furnace kicks in.

Trusting in triticale. Eight New Hampshire farmers have joined with Iago Hale of COLSA and Extension’s Carl Majewski, Steve Turaj and Daimon Meeh to explore the benefits of planting a winter cover crop called triticale, a hybrid of wheat and rye. Typically, fields that yield corn lie vacant through winter. Triticale, planted in the fall and harvested in the spring, offers farmers a second forage crop for their herds and reduces topsoil runoff from snow and rain. The challenge for farmers: to make this work, they have to plant a corn that matures earlier in the season so they can plant the triticale on time.

ONE NATION, FOUR STATESMEN, MILLIONS OF ACRES

Over five decades, four men laid the foundation for the teaching-research-outreach triad that defines land-grant universities today. Here are the key milestones.

TEACHING

Vermonter Justin Smith Morrill spent 44 years in the U.S. Congress between 1854 and 1898. Early in his congressional career, he sponsored legislation to create in every state a college dedicated to the studies of agriculture and engineering. He said the schools should be “accessible to all, but especially to the sons of toil...and where agriculture, the foundation of all present and future prosperity, may look for troops of earnest friends.” The Morrill Act of 1862, signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on July 2, gave eligible states—there were 34 at the time—federal land with which to establish these institutions. Today, there are 235 land grant institutions nationwide.

RESEARCH

William Henry Hatch was a lawyer and farmer who served as chair of the Committee on Agriculture for an entire decade of his 16-year stint in Congress as a democratic Representative to Missouri. A champion of agriculture at a time when farming was becoming increasingly industrialized, Hatch sponsored legislation to establish “experiment stations” at the new land-grant colleges where agricultural research could take place. President Grover Cleveland signed The Hatch Act of 1887 on March 2 of that year. Today, the New Hampshire Agricultural Experiment Station has several active research and field sites on campus and throughout the state.

OUTREACH

In 1914, the year the first stone for the Lincoln Memorial was placed into the ground in the nation’s capital, two members of Congress saw their efforts to improve agriculture on a broad scale realized when President Woodrow Wilson signed the Smith-Lever Act of 1914 on May 8. Wilson described the law, which created the Cooperative Extension system, as “one of the most significant and far-reaching measures for the education of adults ever adopted by any government.” Michael Hoke Smith was a United States Senator from Georgia who had served as Grover Cleveland’s Secretary of the Interior and governor of Georgia before being elected to fill Alexander Clay’s vacant Senate seat in 1911. The son of a farmer, Asbury Francis Lever had a ready-made model of what Cooperative Extension could be: Extension-like work had been going on in his native South Carolina, where tomato demonstration clubs were prevalent and Clemson University professors crossed the state by rail to teach about agriculture and food preservation. Lever taught school for a couple of years before heading to Washington, D.C., and he was chairman of the House Committee on Agriculture when the Smith-Lever Act passed.

SMALL STATE. SMALL FARMS. SMALL POTATOES?

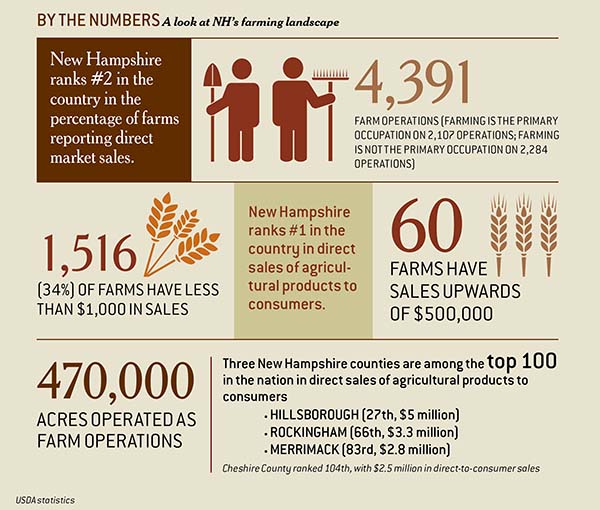

Just how important is agriculture in New Hampshire?

Agriculture makes up a wee percentage of New Hampshire’s economy—a mere drop in the bucket compared to the big farm states of the Corn Belt. But the number of farms has increased steadily over the last 15 years, and the importance of a state’s farming activity cannot be measured merely in dollars and cents. So, just how important is agricultural in New Hampshire?

Lorraine Merrill '73

Important, says New Hampshire Commissioner of Agriculture Lorraine Merrill ’73. “Farmers may be a tiny percentage of the state’s population, but 100 percent of residents and visitors to the Granite State are eaters—with a vested interest in a safe, healthy, and delicious local food supply,” Merrill says, adding that farming “is at the heart of New Hampshire’s cultural traditions, environmental quality and working landscape—all important aspects of our quality of life and tourist economy.”

A strong agricultural sector is important for food security, too, says Joanne Burke, the Thomas W. Haas professor of sustainable food systems at UNH. Today, less than 10 percent of New Hampshire’s food is grown in the state. Burke says with a changing climate, more drought in the nation’s bread baskets and more competition for imports comes less surety that New Hampshire will have an adequate food supply in times of crisis, or with the competition for food that comes with a growing population.

“It really makes sense for more regions to produce more food instead of just one or two areas,” Burke says. She and her collaborators on the report “A New England Food Vision” propose that, with thoughtful, comprehensive planning, at least 50 percent of New England’s food could be produced within the region by 2060.

Originally published by:

UNH Magazine, Fall 2014 Issue

By C. Ralph Adler '76 & Tracey Bentley

-

Written By:

Tracey Bentley | Communications and Public Affairs