Before there can be a dream, there has to be the belief. Not in the dream itself just yet but in possibilities. In yes you can. UNH’s Upward Bound, and counterparts of the federal program across the country, have been teaching that language for 50 years. Born out of President Lyndon Johnson’s war on poverty through the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, Upward Bound is a more-than-summer school program for high school students from low-income families or whose parents do not have a four-year degree. The goal: get those kids to college. And keep them there.

2014 marks the 50th anniversary of the six-week residential program that has students taking classes and living on a college campus. (It’s been at UNH since 1965). This year there are 84 Upward Bound students here, 10 of whom are in what is known as the bridge program—that last sprint of learning to learn before starting college in the fall.

Students take classes in English, math and science as well as mini courses in such subjects as videography, drumming and yoga. On creative problem-solving day teachers (primarily from area high schools) present complex situations for which the students, working in groups, must find the best solution. During student government meetings, the high schoolers are free to offer ideas for the program. There also are study skills and SAT prep classes. And there is that underlining nudge toward believing.

“In the early years, a lot of it was just getting the students to come, live on campus, and believe in the possibility of higher education,” says Dan Gordon, UNH Upward Bound director. “The program was heavily focused on motivation.”

Proof of that lies in a line from a 1971 UNH Magazine article where the author wrote: “Although knowledge and skills are important, the program tackles the more fundamental problem of motivation.”

Gordon, who has been with the program since 1987 and was named director in 1990, says the focus has changed.

“While we still address motivation, our emphasis is more on helping students see themselves differently, and to grow academically,” Gordon says. “Students learn to think outside the box, to work collaboratively and to respect one another, and themselves. For some students, just the idea of college itself is so challenging.”

James SkyHawk Edgell faced that challenge. In 1985, he had just gotten off the streets and back into high school. A struggling student, he was reading at a ninth grade level with the help of a special education teacher.

“I was so far behind. I needed some guidance,” says Edgell, an information technologist with UNH’s Information Technology Services.

His teacher worked hard to get Edgell into a vocational school where he would train to be a welder. But Edgell wanted to go to college. So, the teacher worked some more, looking into Upward Bound. And Edgell was encouraged--until he found out it took place during the summer.

“I said ‘I’m not going to a camp for street kids,’” Edgell says.

But then he talked with the folks at UNH Upward Bound. Three summers later, Edgell was in the top of his class.

“Upward Bound was the key. Upward Bound was the difference. Upward Bound was the possible dream. Socially, educationally, emotionally and spiritually, I grew leaps and bounds,” Edgell says.

Not all students who attend Upward Bound have such struggles. Rachel Landry ’18 was one of Farmington High School’s 2014 top 10 graduates. She applied to eight colleges and was accepted at them all. In the fall she will enter UNH as a biomedical sciences major.

The Middleton resident gives special credit to a component of UNH Upward Bound called “Learning to Study” that exposes students to various learning methods, including working alone, in small groups or one-on-one with a teacher/tutor-mentor.

“Because of Upward Bound, I am better at studying,” Landry says. “It helped me get into a routine of setting small goals each day and motivated me to get as much work done as possible. I will take the studying skills that I learned at Upward Bound with me to college.

“I would not be in the same place if it wasn’t for Upward Bound. The program helped me with everything from researching colleges, to preparing for the SATs, to filling out my common app,” says Landry, the first in her family to attend college.

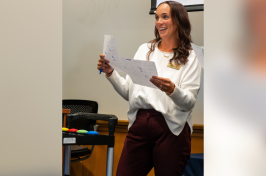

Courtney Marshall is an assistant professor of English and Women’s Studies Program at UNH who also went through the Upward Bound program during high school.

“I did know about college because my grandmother had returned to college when I was younger. However, it was exciting to join a cohort of friends who were interested in working hard on academics in the summer,” Marshall says. “It exposed me to the rigor of college life and enabled me to explore different major options. I’m sure that this was one of the defining moments in my life that led me to be a college professor.”

Upward Bound was the first of three federally funded education programs, now collectively known as TRiO, to come out of the Economic Opportunity Act. (The outreach program Talent Search was launched in 1965. Student Support Services, originally known as Special Services for Disadvantaged Students, was added in 1968.)

No longer a summer-only program, students now meet with advisors throughout the school year. This year, according to the U.S. Department of Education, there are 59,143 Upward Bounders nationwide.

“When students feel safe, are inspired and stimulated, that translates into learning,” Gordon says. “And that can lead to success.”

-

Written By:

Jody Record ’95 | Communications and Public Affairs | jody.record@unh.edu