For two months during the summer of 2013, Daniel Zotos waited at docks in New Hampshire and Massachusetts for fishermen to show up with Atlantic Bluefin Tuna. If they did, he was ready with his questionnaire for the National Marine Fisheries. But, during that time, no one came in with Bluefin tuna.

“I found the job conducting field interviews for conservation efforts on Craigslist,” says Zotos ’14, a political science and international affairs major. It appealed to him because he grew up on an estuarine river in Marshfield, Mass., where he spent hours with his brother, fishing for stripers.

But after awhile, his sense of this critically endangered, large, warm-blooded, high-priced, pelagic fish that could clock about 40 miles per hour and circle the Atlantic with ease, became almost mythic. That past January, a tuna had sold for a record high of $1.8 million in Tokyo to be used for sushi. Eighty percent of all tuna caught are consumed in Japan. As for Zotos, he only got paid for interviews.

“About this time I talked with my adviser Ted Kirkpatrick,” says Zotos. “I was intrigued by the Bluefin tuna fishery and by Spanish language and culture. Ted suggested that I talk with Jeff Bolster and apply for a Hamel Center grant.”

That fall, Zotos read Bolster’s book, The Mortal Sea: Fishing the Atlantic in the Age of Sail. It had recently won the Bancroft Prize, one of the most distinguished awards in the field of history.

“The crux of the book is that this depletion of fisheries in the Atlantic has been going on for millennia,” says Zotos. “It really made sense.”

Bolster was the faculty mentor Zotos had been looking for, but he had never even taken a class with him. When he contacted Bolster about applying for a summer research grant to study Spain’s tuna fishery, “Jeff was right on board from the get go.”

For months, Zotos plugged away at his grant proposal. Through Bolster, he came into contact with Sergi Tudela, head of fisheries, World Wildlife Fund (WWF) Mediterranean. Zotos Skyped with Tudela to discuss the project, and Tudela agreed to be his mentor in Spain.

“Sergi’s life’s work is to save the Bluefin tuna,” says Zotos. “He said, ‘Daniel get over here. We’ll meet. I’ll make contacts. It’s all about timing.’”

And so last summer Zotos flew to Barcelona to investigate the practices and policies associated with the Bluefin tuna fishery along the coast of Spain. There he interviewed staff members at the WWF in Barcelona, one of the environmental groups that had successfully pressured the government agency, the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), to place stricter quotas on tuna. He then traveled to Madrid and interviewed members of ICCAT.

Most importantly, he interviewed fishermen from two of Spain’s three major tuna fishing regions: the Catalonians in the south—purse seiners (fisherman who use a specific type of net), and the Almadraberos of the southern Andalucía region who use an ancient method called the “almadraba.” He had planned to interview Basque fishermen, who fish using long lines, but they had sold their quota to Ricardo Fuentes and Sons in Catalonia.

In Andalucía, Zotos was on his own. Because, as Tudela explained, he was partially responsible for cutting their quota, consequently Tudela wasn’t very popular there. So Zotos hit the road and wandered the streets of Barbate, an impoverished coastal town. Finally through an odd series of coincidences, Zotos met a fisherman named Rafa. Soon with Rafa as his guide, Zotos was touring the old fishing boats in the harbor and learning about the “almadraba,” a maze of nets that sort and trap only tuna of harvestable size. At the last juncture, lines of fishermen hook and harvest the tuna.

Later Tudela commented to Zotos, “If all tuna were fished by that method, the fishery would be sustainable.”

In Catalonia, tuna are fished using purse seines, a method that employs planes to spot for schools of tuna and signal boats, which encircle the fish with a huge net. When the bottom of the net is cinched, like a purse, the catch is hauled in. Zotos tried to meet with the largest company, Ricardo Fuentes and Sons, but to no avail. Finally, he visited Grupo Balfuegó, a Catalonian company that claims to manage its catch sustainably by capturing tuna only after they’ve spawned. Then the tuna are fattened in pens and harvested as orders come in from restaurants around the world.

While touring the pens, one of the workers asked Zotos if he wanted to swim with the tuna. It’s a fairly common invitation and as they chummed for tuna, Zotos jumped in with his GoPro camera.

“My heart was blasting out of my chest. These fish have tails like bullwhips, but they’re so well designed, they sense you and never hit you,” says Zotos. “They’re like a fish out of the movie Avatar."

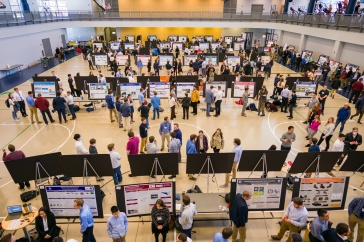

Zotos will present his findings at the Undergraduate Research Conference in April. He plans to continue his study of international fisheries with possible plans for law school. But most of all, he’s hopeful for the Bluefin tuna. When looking at a graph showing a precipitous drop in stocks, he points to where it goes up slightly and notes: “That’s because of quota restrictions.”

Learn more about Daniel Zotos’s research project in his self-produced video, Politics of Fishing (The Case of the Bluefin Tuna). Note: I'd like to thank Rafael Grenuido for contributing photographs and Tyler Collins ’15 for his assistance with video editing.--Daniel Zotos

W. Jeffrey Bolster, an associate professor of history at the University of New Hampshire and professional seafarer, discusses his book, The Mortal Sea: Fishing the Atlantic in the Age of Sail.

Originally published by:

The College Letter, Newsletter for the College of Liberal Arts