DURHAM, N.H. – Legislative funding cuts to a New Hampshire program designed to help the state’s troubled youths and help curb delinquent behavior and juvenile offenses resulted in a steep drop in the number of Granite State youths served by the program while reports of child maltreatment increased, according to new research from the Carsey Institute at the University of New Hampshire. The research was supported by New Hampshire Kids Count.

“As an independent advocate for child well-being, NH Kids Count recognized the negative effects of changes to the New Hampshire Child in Need of Services (CHINS) program. Some children and youth no longer had access to the services they needed. Even as we pursued legislation to address the situation, we also sought appropriate research to inform long term solutions. Legislators, advocates and community members will be able to make smart, long-lasting decisions based on the data in this brief,” said Ellen Fineberg, NH Kids Count executive director.

In 2011, legislative budget cuts resulted in a change in the law governing eligibility for services through the CHINS program to only youths diagnosed with the most severe emotional problems and behavior. The program’s original intent was to help families of children who engage in noncriminal behavior such as skipping school, running away from home, violating curfew laws, and breaking underage drinking laws. It is designed to help families curb unruly behavior and get their children back on track so that youths do not progress to more serious offenses that would result in subsequent involvement in the juvenile justice system.

Lisa Speropolous, a doctoral student in sociology at UNH and a research assistant at the Carsey Institute, and Barbara Wauchope, director of evaluation and a research associate professor at the Carsey Institute, found there was a steep drop in the number of families and children served after the state changed who was eligible for CHINS services because of loss of funding.

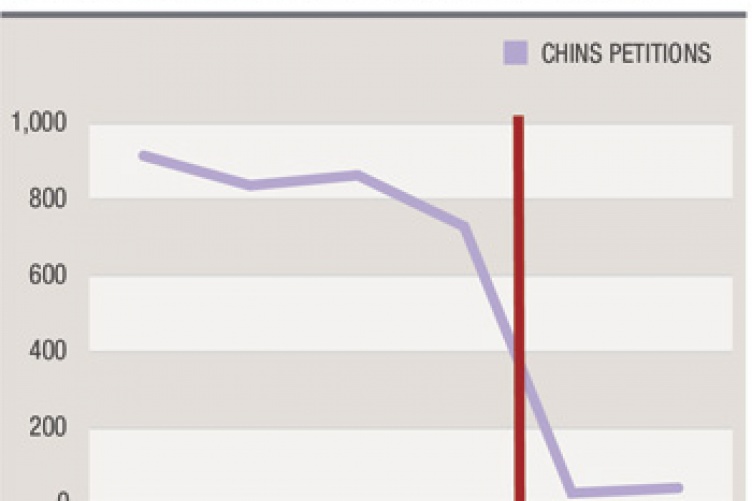

From 2011 to 2012, the number of children who received services through the program dropped by 56 percent, from 751 to 329. The decline continued from 2012 to 2013 by 73 percent, for a two-year decline of 88 percent. At its lowest point in 2013, the program served just 89 children.

“As a result of this change, the state no longer could serve children with less serious truant, runaway, and other misbehaviors. Instead, responsibility for addressing these children’s needs shifted to local communities where families, schools, law enforcement, and service providers were tasked with handling them without the resources and court-ordered support previously available to them under the former CHINS law,” the researchers said.

The Carsey researchers found that following the law change, the number of reports of child maltreatment – such as child neglect and child abuse – increased by 13 percent. “A child’s behavioral problem can be an indicator of a larger family issue, for example, child neglect or substance abuse by family members in the home. Court-ordered treatment or services often includes addressing these familial issues,” the researchers said.

The Carsey researchers also found that narrowing who was eligible for the program had a detrimental impact in communities served by the program because they had fewer services and supports to deal with issues such as truants, runaways and less severely mental ill youths.

“Truancy at an early age has been found to increase the likelihood of engaging in delinquent behavior during adolescence. It also has been linked to chronic unemployment and criminal behavior during adulthood, all arguments for requiring children to attend school. However, when the change in the CHINS law removed truants from those eligible for CHINS, the state lost the means for delivering consequences to students who skip school. Administrators at several schools reported increased truancy problems as a result,” the researchers found.

When funding was restored in September 2013, the law broadened eligibility for services.

“This situation, had it continued, could have led to an increase in delinquent or criminal behavior over time with ultimately more serious consequences for New Hampshire’s communities. However, the decision by the N.H. Legislature in 2013 to restore eligibility to a broader range of children and to provide funding makes such a scenario unlikely and, instead, re-establishes a support system for these troubled or disconnected youths and their families,” the researchers said.

This research was supported by NH Kids Count and its funders. It is based on data from state and local agencies, and data from interviews with Child In Need of Services professionals. The research is presented in the Carsey Institute brief “New Hampshire Children in Need of Services: Change in Eligibility Cuts Services to Children,” which is available at http://carseyinstitute.unh.edu/publication/961.

The Carsey Institute conducts policy research on vulnerable children, youth, and families and on sustainable community development. The institute gives policy makers and practitioners the timely, independent resources they need to effect change in their communities. For more information about the Carsey Institute, go to www.carseyinstitute.unh.edu.

New Hampshire Kids Count is dedicated to improving the lives of all children by advocating for public initiatives that make a real difference. It ensures laws, policies, and programs in the Granite State are effective, improve kids’ lives, and keep them well. For more information on N.H. Kids Count, visit www.nhkidscount.org.

The University of New Hampshire, founded in 1866, is a world-class public research university with the feel of a New England liberal arts college. A land, sea, and space-grant university, UNH is the state's flagship public institution, enrolling 12,300 undergraduate and 2,200 graduate students.