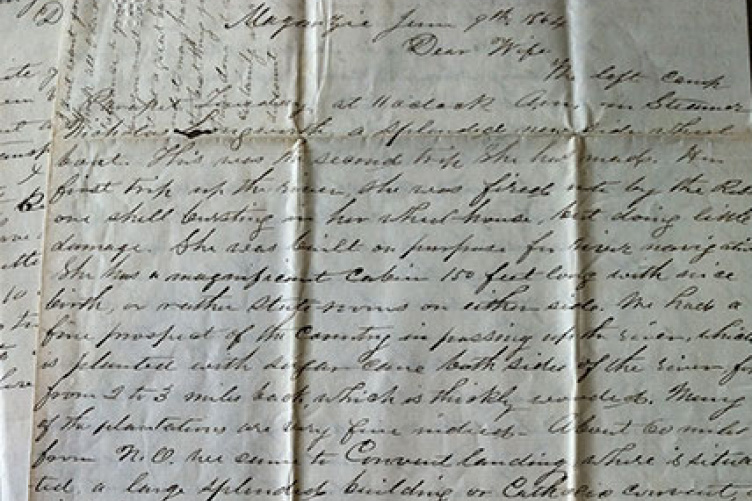

Letter written by John Henry Jenks, a soldier from Keene who served in the 14th N.H. Infantry Regiment, to his wife dated June 9, 1864.

Despite New Hampshire being one of the most liberal states in the nation at the time of the American Civil War, racism was common in the letters of New Hampshire soldiers, including those who said they supported freeing the slaves.

University of New Hampshire senior Nathan Marzoli, a history major from Dover, investigated the attitudes of New Hampshire Civil War soldiers for his senior undergraduate research project, “New Hampshire Civil War Soldiers and Slavery.”

“Similarly to the rest of the nation, there appeared to have been a huge variety of views among New Hampshire soldiers on the issue of slavery. Many of the soldiers, especially the more educated officers, were abolitionists. Their views against slavery only intensified when they encountered it. On the other end of the spectrum, there were also soldiers who were completely against fighting to free the slaves and noted this in their correspondence,” Marzoli says.

“Racism was abundant in almost all of the soldiers’ letters and diaries, however. Even the staunch abolitionists saw black people as almost inhuman and comical. However, they were not usually as derogatory as those who were against freeing the slaves,” he says.

For his project, Marzoli relied on primary sources such as the actual letters written by New Hampshire Civil War soldiers. Among the most memorable examples he found were the letters of John Henry Jenks, a relatively old soldier – he was 40 years old – from Keene who served in the 14th N.H. Infantry Regiment.

“Although Jenks appeared to be an abolitionist, he never made mention of the topic in a political sense. Instead, he seemed to deeply care for the slaves’ plight and saw them almost as equals. Jenks thought that blacks were no different than whites, and because of this he seemed to be incredibly ahead of his time. He was definitely an anomaly, but unfortunately he was killed at the Battle of Cedar Creek in 1864,” Marzoli says.

Marzoli found that, by and large, the attitudes of New Hampshire Civil War soldiers toward slavery were tied to their upbringing and education level. “The more educated officers and soldiers appeared to be more abolitionist, while the common soldiers could often be very racist. Although none of them owned slaves, they simply had their own opinions on the hot topic of the day, just as we do in the present day,” he says.

In addition, for some soldiers, encountering the brutality of the institution of slavery for the first time resulted in a shift of their views. “I never noticed an extremely drastic change in opinion, but some of them definitely became more opposed to human bondage,” Marzoli says.

In looking at the process of reconciliation, Marzoli found that the New Hampshire soldiers had to try and forget about the issue of slavery.

“David Blight’s ‘Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory’ offered great insight into the nation’s methods of reconciliation after the war. In the 1880s and 1890s, reconciliation became incredibly important to both the Union and Confederate veterans. They wanted to put aside their differences and unite in the fact that they had both fought valiantly for their respective causes,” Marzoli says.

“Unfortunately, this meant that the former hotbed issue of slavery was put on the back burner. During this time, numerous memoirs and regimental histories were compiled and written, and interestingly, slaves and black men no longer had a key role in the events. They were mostly delegated to subservient roles in the memories of these soldiers in order for the nation to heal its wounds,” he says. “In other words, New Hampshire soldiers had to forget to move on.”

Marzoli will present this project at UNH’s Undergraduate Research Conference, the largest event of its kind in the country, Thursday, April 25, 2013, at the History Department’s Undergraduate Research Conference presentations. The presentations will be held from 12:30 to 2 p.m. in the Memorial Union Building, Rooms 338/340 and Theatre I.

Originally published by:

UNH Today

-

Written By:

Staff writer | Communications and Public Affairs