Ed Wong Mentored a Generation of Scientists

|

|

This summer, an era quietly closed at the College of Engineering and Physical Sciences.

Ed Wong retired.

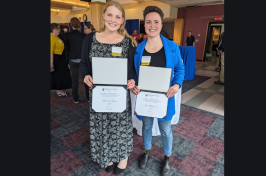

He retired the way a talented scholar and teacher who has inspired a generation of students ought to retire: he was awarded a Graduate Faculty Mentor Award, his second faculty excellence award in the past decade. “This may be a kind of ‘lifetime achievement award’ since I’ve been here so long,” quips Wong with the kind of sly, self-deprecating humor that adds wit and edge to most of his observations about himself.

And then he adds, more seriously, “Actually, it’s a departmental award more than an individual award. After all, this chemistry department builds the culture that nourishes teaching and research that continues to sustain itself. I’ve been lucky to find the right fit at UNH.”

Luck may have played a part in Wong’s career, but luck doesn’t explain the bookshelf creaking under the heft of the many doctoral and master’s theses Wong has directed since he arrived at UNH in 1978 as an assistant professor of chemistry. Fresh out of Harvard, where he worked in the lab of the legendary Nobel laureate William “Colonel” Lipscomb, Wong hoped that his own lab would be a place where “students at all levels” would come together to pursue research that can also keep teaching cutting edge and exciting.

|

Ed Wong became a diehard Red Sox fan at Harvard and remains passionate about the team's fortunes. |

From the moment he set foot in Parsons Hall, Wong began to mentor graduate students, who worked side by side not only with him, but also undergraduates, other professors, and, later, post-doctoral associates. Through the years, Wong has trained more than his share of “star” students who have come to UNH ready (and able) to move mountains; but he has also reserved a special place in his heart for those whose journeys were a bit bumpier.

“When we look back at a career or a program, we tend to focus more on the strong students,” says Wong. “Yet, I am perhaps proudest of the ones who struggled. I think of the student who comes from another country. Maybe she didn’t get the kind of training others did: not enough experience in a real lab. She falls behind immediately and has confidence issues.” For such a student, catching up can seem impossible, says Wong, and the pressure to “give up” is strong.

But for many of these students – and here Wong smiles a wide, bright smile – “often a light goes on and the work starts to become more competent. And it then stays at a high level.

“So what’s the secret? What happens? Persistence, patience, and hard work. No short cuts.”

Perhaps Wong sees something of himself in this hypothetical weary traveler. Born in mainland China, Wong’s family moved to Hong Kong as a child to enjoy more freedoms. In high school, he learned English from reading history books – he still holds a passionate interest in U.S. naval history, born of witnessing navy ships that pulled into Hong Kong harbor – and excelled at science. Continuing his westward migration, in 1964 Wong enrolled at Cal-Berkeley.

|

Ed Wong (second from right) and Gary Weisman (third from right) with some of the many students they trained in their lab. |

With a taste for San Francisco’s Chinatown and the fabled concert venue Fillmore West, Wong went to hear rock icons such as Janis Joplin and Jefferson Airplane and immersed himself in the unique cultural milieu of that era. “Coming from China, you study, study, study. Right? It was easy for me at Berkeley to get good grades,” he recalls. “In fact, I probably had too easy a time.”

While Wong views research as a tremendously powerful force in undergraduate as well as graduate education today, he wonders whether his own road might have been easier had he applied himself earlier. “To me, undergraduate research pretty much meant throwing dry ice from the lab window down into the fountain below to watch the smoke come up and startle the passersby,” says Wong. “At Harvard it was much harder for me. I was used to being the best.”

At UNH, Wong, an inorganic chemist, initially did what he calls “blue sky” chemistry, assembling Boron atoms into clusters and studying their physical and chemical behavior. “Very basic science,” Wong explains. “It was fascinating fundamental work. But, compared to what I have done in the latter part of my career, it was pretty esoteric.

Indeed, Wong dates his proudest research accomplishment to his partnership with fellow UNH chemistry professor Gary Weisman. Beginning in 2000, the pair collaborated on the design and synthesis of tumor detection molecules to carry a radioactive copper isotope. Delivered selectively to tumorous cells after linking to targeting peptides by another collaborator at Washington University, St. Louis, Wong and Weisman’s molecules can light up and reveal tumor sites by positron emission tomography in a hospital clinic.

Not only can Wong and Weisman’s work lead to an important diagnostic tool in the fight against cancer, it has already provided over a decade’s worth of stellar opportunities for chemistry students to take part in meaningful research. But Wong’s influence goes beyond any specific lab experiment or published research paper and ultimately rests with the example of the man himself.

Xiankai Sun earned a Ph.D. in Chemistry under the guidance of Wong in 2000 and is now an associate professor at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Sun says having his own graduate students make him “deeply appreciate how Professor Wong’s commitment to excellence in graduate training creates opportunities for professional advancement.”

Sun describes Wong as “the role model of my own graduate teaching and scientific research.” He often encourages his own students by telling them how “red inked” his first experimental report came back from Wong. “This reminds me of being patient with students and the teaching philosophy that I learned from him.”

Now that the future of chemistry teaching is passing into capable new hands in his own department, Wong plans to garden and play more tennis with his wife at their Brentwood home, and hopes to continue to hike the region’s highest peaks with his son who shares his love of the outdoors.

He’ll also finish out the final year of his participation in the famous Wong-Weisman partnership. Will the research continue to go on after Wong bows out, he is asked? “Oh, yes. The research always goes on.”

Originally published by:

UNH Today

Written by Dave Moore, Editorial and Creative Services. Top photo by Mike Ross, UNH Photographic Services. Bottom photo by Lisa Nugent, UNH Photographic Services.