If numbers were shouts, Gary Langer's office at ABC News would sound like Yankee Stadium.

Numbers call to him from printouts piled high on the glass-topped coffee table. Stacks of stats in tiny type spill across his desk, bumping the bottoms of two large computer monitors. Over by the window, stray survey pages have drifted to the floor. He'll pick them up someday, but right now, more numbers are calling. They beep into his e-mail inbox; they buzz into his BlackBerry. Questions about numbers keep his phone ringing and his assistants striding in and out with new piles of data.

"Make sense of me!" the numbers beg. "Put me in context. Help me tell a story." And all day, as polling director for the network, Langer does the numbers' bidding. All day, and sometimes into the night, the data cop works the beat. If ABC is going to use a number, it had better be a reliable number, one that Langer has stamped with his ultimate term of approval: airworthy. If the sample or the questions or the analysis doesn't meet the standards of Langer and his staff, ABC News will not use the poll--even if it's cool and sexy and every other news organization is putting it in headlines.

Call him the data wrangler, the number whisperer. Call him the network's top cop, as Freakonomics author Steven Dubner does in his New York Times blog. Call him rigorous, as "World News Tonight" anchor Charles Gibson does in his office, or meticulous, as senior national correspondent Jake Tapper does on the air. Call him the Poobah of Polling, Langer's joking nickname for himself on his ABC blog "The Numbers." But above all, call him a journalist. "I am not a pollster," Langer says early and often. "I am a journalist who does polls. I cover a beat, the beat of public opinion."

His 22 years on that beat have created demand for his speeches and analyses everywhere from The Washington Post and National Public Radio to The Journal of Pain. Under Langer, the polling unit won its second Emmy award this fall (the only two Emmys ever to cite public opinion polls) and has earned three more Emmy nominations. Both awards were for ABC's work on "Iraq: Where Things Stand." The giant megaphone of ABC News shouts his unit's research to the world. That research includes the expected, like election polls and consumer confidence surveys, and plenty of the unexpected: polls of civilians in Iraq and Afghanistan, polls on manners and motherhood and Americans' satisfaction with their sex lives. For each poll, the unit releases not just a summary and analysis but the full questionnaire and results, all stored in the online "poll vault." (http://abcnews.go.com/pollingunit/) "Here's the data," Langer is saying. "Take our word for it, or drill as deep as you want."

Conducting polls is Langer's job; educating people about polling is his mission. For the ABC News web site, he's written a guide to polls for the uninitiated. If people are wondering, for instance, why ABC News pollsters now make calls to business phones, he wants to be sure they have a place to look for answers. Langer has spent years agitating for other news organizations to establish a vetting process like the one his unit employs. He counts it as progress that similar operations are now taking hold at the Associated Press, the Times and the Post (where the polling director is Langer's former assistant).

n this epic campaign year, when polls have come under extra scrutiny, Langer is one of the nation's most prominent, and ardent, champions of professional survey research. Sure, he tells people, get annoyed by the lousy polls, the ones with "squirrelly" methodology or inaccurate samples--for instance, a poll of Americans in "hurricane zones" that included people living far from any coast. Look with skepticism on all polls, he says, especially the ones done by groups with self-serving motives. The hurricane survey, which found Americans alarmingly unprepared, was sponsored in part by a manufacturer of storm protection products. Needless to say, ABC didn't use the poll.

"At ABC News we try like hell to produce good research. But we burn just as many calories trying to kill bad research," Langer says. So yes, it's crucial to look critically at all survey research--but it's equally crucial that we never stop looking. He firmly believes that no one can be a responsible participant in democracy without paying attention to polls. For one thing, many of the statistics that shape our lives--about health, crime, the economy--come from polls. For another, understanding the world means understanding not just what people do but what they think. "Public opinion has been an essential element of public discourse since time immemorial," Langer says. "Like it or hate it, we strive to know it, and for good reason: It matters."

The Natural

Langer, whose mother is a professor of literacy, never planned to become a de facto professor of numeracy. He wanted to be a reporter, and he chose UNH because the journalism program offered full-time reporting internships. "From the beginning, Gary was a natural," recalls journalism professor Andrew Merton '67. Then as now, Langer tolerated no nonsense. If he was interviewing someone who was trying to snow him, Langer would say quietly, "Mr. Smith, I'm confused." If the snow job continued, Mr. Smith could expect to see his evasion in print.

When Langer graduated in 1980, Jon Kellogg '70, then AP bureau chief in Concord, N.H., hired him as a reporter. "The kid" quickly impressed longtime staffers with his ability and tenacity. "He had a dry sense of humor and a quick wit," says Kellogg. (Those qualities are still evident in some Langer headlines, like "No Huckaboom" on candidate Mike Huckabee's numbers.)

Langer had been accepted at Columbia's graduate school of journalism but chose to stay with the AP, in Concord and later New York. He started working on a small weekly AP poll, studying polling the way a reporter studies any beat--by reading, interviewing experts, taking a course. He had long noticed that even some good reporters were "data-hungry but math-phobic." The more Langer learned about polling, the more he saw this aversion to numbers as not just lazy but dangerous. "I launched what could be fairly called a crusade to change things," he says.

He moved to ABC in 1990 as senior polling analyst and became polling director in 1998. Despite his passion for his work, sometimes--especially in an election year--he'll stop to remind his news-obsessed colleagues: Some of this data won't matter to "normal people who have actual lives." He's careful to maintain an actual life himself, much of it happening not far from ABC's offices on the Upper West Side. Langer and his wife and two daughters share a two-story co-op with that rare Manhattan commodity, a private, tree-shaded backyard. When he's home, he's often building something--a small waterfall, a potting shed-turned-playhouse, an old-fashioned dollhouse with crown molding and working chandeliers. His method of commuting to work is old-fashioned, too. "Mommy," he heard a little girl say as he whizzed by one morning, "there goes an old man on a scooter!"

Fie on conventional wisdom

Three things never to say to Gary Langer:

- Polls are no substitute for good reporting.

- That poll doesn't represent my opinion because nobody asked me.

- But everyone I know thinks ...

Better still, go ahead. He's heard it all before, and his answers provide a short course in the basics of opinion research. Polls aren't a substitute for reporting, Langer says; good polling is reporting. A reporter tries hard to choose representative sources and analyze the resulting information fairly. A pollster goes further, randomly selecting large numbers of sources with absolutely no idea what information they'll provide. (By "large numbers" he does mean large--for example, the 79,281 voters interviewed by a consortium of news organizations during exit polls in 68 presidential primaries this year.)

As for "nobody asked me," the point isn't whether you were called for a particular survey (as Langer says, it's a big country with a lot of phones); the point is whether your chances of being called were the same as everyone else's. He explains with a standard pollster joke: If you don't believe in random sampling, the next time your doctor tests your blood, have him take it all.

If the opinions measured by surveys look different from the opinions of the people you know--well, that's the point. You know only a tiny portion of the population; polls give the other portions equal weight. Polling "enables us to give voice to those who lack it, to assess attitudes independently," Langer says. Independence means that the Poobah of Polling pooh-poohs conventional wisdom. When Ronald Reagan died, everyone's first impulse was to reminisce about his great popularity as president. But the huge database Langer's unit has accumulated allowed him not just to question the prevailing view but to back up his doubts with facts. Among the 11 postwar presidents, it turns out, Reagan's average approval rating ranked fifth, tied with Bill Clinton's. Analyzing data begins with attitude, and Attitude Number One is to clear the mind of assumptions. Or as Langer puts it: "You don't sing to the data; you let the data sing to you."

Doing the Charlie-Charlie

In the commotion at ABC News on the last day of the presidential primaries, it's hard to hear the data singing. Langer is coming off a late night spent crafting an analysis of what the campaign so far might signify for the months to come. He knows that what's happening in South Dakota and Montana on this June day will be just a sidebar to the big question: Will Barack Obama lock up the Democratic delegate count? The morning moves quickly from polishing the analysis to promoting it--first making sure it's linked to the ABC News homepage and then making sure everyone he encounters has seen it.

It's important to keep the polling unit's work out front, Langer says, to help everyone distinguish small from large, the campaign from the election. A campaign focuses narrowly on one thing: victory. When people grouse that journalists overemphasize the "horse race," they're complaining about campaign coverage. To Langer, an election is something much broader and more profound. "It's the people of this country evaluating where we're at, where we want to go, how we want to get there, and what's informing all of those."

He's happy to spread this gospel by any means necessary--including, on this day, summarizing his campaign analysis for ABC Radio. That means condensing 1,600 written words to 20 seconds, a task he chips away at, between phone calls, on one of the numerous windows open on his two computer screens. In another window he's assembling a response to correspondent Jake Tapper, who has asked whether Langer has numbers on "angry Clinton supporters" who might not switch to Obama. Anger is not what he's seeing in polls, Langer thinks, so he's trying to refocus the question while gathering relevant data. "Jake will be on 'World News' tonight and 'Good Morning America' tomorrow, and today he's blogging," Langer says. "If we don't address this now, we have the opportunity to misinform several million people."

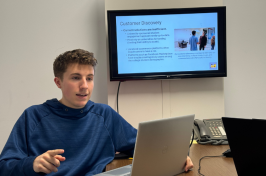

TWENTY SECONDS: Gary Langer '80 records a spot for ABC Radio, above, and

commutes to work on a scooter, left.

After quick staff meetings, Langer returns to the radio piece. Recording these spots is known around the building as "doing the Charlie-Charlie" because the first and last words spoken in the 20 seconds are anchor Gibson's first name. "Charlie," Langer begins in an introductory tone, leaning toward the microphone. Then again at the end, in a back-to-you voice, "Charlie?"

Downstairs in his office, Charlie himself sings Langer's praises. "It's tremendously valuable that his origin is in reporting; he's not a data-head," Gibson says. Not long ago, an Obama campaign pollster said to Gibson, "Why are you asking about my polls? ABC's polls are the gold standard." As the epitome of the unit's efforts, Gibson points to the three polls ABC has conducted in Afghanistan and the five in Iraq.

UNEXPECTED FINDING: Kate Rice, second from

left, pulled off a surprise 50th birthday party in

July for husband Gary Langer '80, left. Below,

Langer and daughter Gavriela, 6, in Central Park.

"Iraq: Where Things Stand" has won ABC News five Emmy awards, including the two that cited the polling unit, but awards are not what the people in the news division talk about. They talk about the honor of being allowed into Iraqis' homes, the importance of understanding life in a country in a far deeper way than casualty counts. The thousands of interviews over five years produce a picture of what matters to Iraqis and of the gradual changes in their daily lives--feelings of safety or danger, access to electricity and clean water and medical care.

The Iraq and Afghanistan polls give voice to people rarely heard from. Figuring out how to make the polls happen gave new meaning to the term "roadblock." Langer first had to locate companies that were willing and qualified to do surveys in dangerous areas. His most recent polls in Iraq required extensive work on the questionnaire itself, careful translating and re-translating, a lot of training of the field staff and a lot of worry about their safety. Iraqis did the polling in their home regions. They fanned out from more than 400 starting points across the country, following a random-route procedure to choose homes and knock on the doors. For their own protection, the field teams didn't know who was sponsoring the poll. Shiites asked the questions in Shiite areas, Sunni Arabs in Sunni areas, Kurds in Kurdish areas. In mixed areas, some interviewers carried dual forms of identification with separate Shiite- and Sunni-sounding names.

Over the years of the project, interviewers have encountered explosions, police checkpoints, detentions by armed militia, and plenty of grilling about what they're doing and why. So far, however, everyone has returned safely. Interviewers report that most people, especially women, are flattered to be asked their opinions. The response rate in the 2008 Iraq poll was 65 percent; in the United States, Langer says, ABC is happy with 40 percent.

Brainstorming the next international poll is among Langer's favorite occupations, along with imagining new ways to look at data. Before he can move to new projects, however, there's the matter of the Democratic primaries to wrap up. Early exit poll results from South Dakota have started to arrive in time for the 5:40 pre-newscast briefing. Though Langer has already written a quick analysis, he says little at the meeting. In fact, after the long primary season, most of the producers and correspondents slumped against the walls look exhausted. When it becomes apparent that in less than an hour ABC will announce on "World News Tonight" that Obama has, in fact, gained enough delegates to assure him the nomination, people barely react.

Langer and several colleagues head for the elevator. Though they're traveling only a few floors, they immediately start tapping away on their BlackBerrys. "Is it really over?" someone asks. Langer glances up for a second, smiles, and returns to his tiny keyboard. More numbers are calling, and they can't wait.~