Anyone driving through the old mill towns of Seacoast, New Hampshire in 1974 might have encountered a local bumper sticker with the slogan, “Let those bastards freeze in the dark” (Manchester Union Leader, 1974). These stickers were not random threats wishing hypothermia and frostbite on their neighbors. Instead, they represented one side in a battle that polarized the Seacoast region of the Granite State—whether to allow Greek shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis to build an oil refinery in Durham, home of the University of New Hampshire (UNH). Much like 2022, 1974 was a year of high gas prices, which made the refinery fight particularly bitter.

The author, Samantha DiNatale

The side that advocated for the establishment of the refinery has usually been left out of relevant literature. Works such as David Moore’s Small Town, Big Oil: The Untold Story of the Women Who Took on the Richest Man in the World — and Won and Lisa Moll’s Rye’s Battle of the Century: Saving the New Hampshire Seacoast from Olympic Oil focus on the triumphs of those who successfully fought off the industry. These individuals included Dudley Dudley, a political activist and eventual New Hampshire Executive Council member, who took the fight to the state legislature despite New Hampshire Governor Meldrim Thomson’s staunch pro-refinery efforts; Phyllis Bennett, the newspaper publisher of Publick Occurrences, who originally alerted local citizens of the secret land grab attempts for space to build the refinery; and Nancy Sandberg, leader of Save Our Shores (SOS), a group dedicated to keeping the Isles of Shoals and the Great Bay clear of the supertanker refinery. Engravings on park benches were also made in dedication to them, memorializing the sentiments of pride and gratitude for these women who saved Durham and the surrounding Seacoast from further industrialization.

Such an achievement in this battle that Moore would come to describe as “David vs. Goliath” deserves the recognition it receives (Moore, 2018). However, the supporters and their opinions have largely been ignored, leaving out a side of a story that is crucial to understanding both the events that took place and the wider societal conditions of the 1970s. Framing the story of the Durham refinery in a way that makes it seem as though the situation was good vs. evil, or “David vs. Goliath,” is not an accurate representation. It is important to fully comprehend both sides of the story in order to completely understand what occurred on the Seacoast, and why this triumph for environmentalists turned out the way it did. To paint the supporters as villains ignores the economic struggles they were facing and disregards the conditions that led them to have these beliefs. Therefore, with this research, I set out to document the views of the “other” side and how it was portrayed in media.

As an environmental conservation and sustainability and history double major, I’ve always been partial to examining the intersection of the social sciences and environmental issues. This project, an environmental history case study pertaining to Durham’s history, was introduced to me by my mentor, Professor Kurk Dorsey, chair of UNH’s History Department, who has a similar interest in environmental history. Supported by funding through the Ronald E. McNair Post-Baccalaureate Achievement Program, I could not pass up the opportunity to spend the summer engrossed in a project I was passionate about, while simultaneously becoming better versed in the methodologies associated with historical research.

Uncovering the Context

My project began with reading secondary sources, or works that offer analysis, interpretation, and synthesis, of primary sources, which provide the raw, firsthand data (i.e. anything such as diaries, maps, letters, etc., from the period in question). From these works, including those previously mentioned by Moore and Moll, as well as Environmental Inequalities: Class, Race, and Industrial Pollution in Gary, Indiana, 1945-1980 by Andrew Hurley and From the Mountains to the Sea: Protecting Nature in Postwar New Hampshire by Kimberly Jarvis, in addition to knowledge garnered from courses I have taken as major requirements, I was able to flesh out the context of the refinery proposal.

The social, economic, and political conditions of American life in the 1970s set the stage for the proceedings that took place on the Seacoast of New Hampshire. Arguably one of the most important events underway during the early 1970s was the oil embargo plaguing the United States, which was prompted by President Richard Nixon’s financial aid to Israel in the Yom Kippur War. This oil embargo, imposed by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), banned petroleum exports to the targeted nations, which included the US and much of Western Europe, and cut oil production levels (Stork, 1974). OPEC, which was founded in 1960, consisted of nations from regions such as the Middle East, northern Africa, and South America. Such production cuts dramatically raised the price of oil. In addition to increased prices, the US had no ability to bring more oil into the market quickly enough to make a difference. This lack of oil manifested in numerous different ways, from a lack of heating oil to warm homes, to a great loss in petroleum to power vehicles. Lines at gas stations stretched out, with some people parking their cars and leaving them overnight to remain in their spot for the next day.

The impacts of America’s industrialization were simultaneously becoming more apparent to the nation. In 1969, environmental disasters such as the Santa Barbara oil spill and the Cuyahoga River fires, the latter of which was sparked by an oil slick in the water being set ablaze, triggered American concern for the environment. Animals suffocating from a shiny, black liquid and a body of water catching aflame seemed apocalyptic to the American public, and many of them called for action. In the following year, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was created by Richard Nixon, and the first Earth Day was celebrated by Americans across the country. Additionally, the reissuing of A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold in 1966 and the publishing of Silent Spring by Rachel Carson in 1962 had brought about a sense of urgency and stewardship regarding the environment. The release of Carson’s work is often viewed as the onset of the modern environmentalist movement, an era of history that played a prominent role in the tale of Durham’s proposed oil refinery.

Methodologies in Archival Research

After my preliminary research into the social and political climate of the ’70s, I turned my research focus to the refinery proposal. I relied heavily upon secondary sources to build a concrete understanding of the refinery proposal itself, and primary sources to better understand the opinions of those who supported the construction.

Model of the proposed Durham refinery, as made by Olympic Oil. Photo courtesy of Milne Special Collections. Click to enlarge.

To analyze media published in the region during this period, I utilized the Milne Special Collections and Archives within UNH’s Dimond Library, as well as the Newmarket Historical Society. Both had a vast collection of newspapers from the era in question, which offered commentaries, opinion articles, and more from Seacoast residents who were both proponents and opponents of the refinery. I specifically focused on the content published in Publick Occurrences as it was a highly popular newspaper at the time. With the help of Bill Ross of Milne Special Collections and Archives, and Dr. Kimberly Alexander and John Carmichael of the Newmarket Historical Society, I was able to access these records, analyzing them to identify common themes. It was at these local sites where I took pictures of the sentiments that were of interest, before taking them back to my dorm room to read more deeply. This research was conducted during COVID-19, so I wanted to minimize my time in public spaces in order to promote public health on campus and in surrounding communities.

The Refinery Proposal

With my thorough understanding of the social and political climate of the ’70s, I could see why it was prime time for Onassis to swoop in and propose to construct a massive oil refinery on the Seacoast of New Hampshire. The location of Durham was perfect in the eyes of those intending to build the refinery due to its geographic proximity to the Isles of Shoals, where the offshore terminal was proposed. The refinery proposal included “nine pipelines running through Rye and Portsmouth ranging up to 48 inches in diameter, and a truck terminal in Portsmouth near Interstate Highway 95” (Deal, 1975).

Political cartoon made by opponents depicting Durham as a puzzle with Aristotle Onassis putting down pieces as he acquired land for the refinery. Photo courtesy of Milne Special Collections. Click to enlarge.

Additionally, “it would [occupy] 3,000 acres in Durham alone [and] cost about $600 million to construct” (Deal, 1975). This plant, Onassis’s team promised, would bring an abundance of fuel, jobs, and tax revenue to the area. If built, it would have been the largest refinery in the United States with a capacity of 400,000 barrels of oil with the capability of inflating it to 600,000 barrels (Deal, 1975). It would transform the sleepy Seacoast into a bustling hub of industry, requiring high amounts of land and natural resources.

Despite this economically favorable proposal, two sides quickly formed in response. A vast number of local residents were against the refinery due to its environmental and aesthetic implications, as well as the potential changes to their known ways of life. However, proponents of the refinery sought to benefit from the economic gains the refinery promised to provide.

Such economic gains, as promised, included 2,500 jobs associated with the refinery’s construction, and another 1,000 job opportunities once it opened for operation purposes (Deal, 1975). Additionally, according to Onassis and his corporation, “the new refinery would hand out payroll checks of $10 million a year and generate some $80 million a year in economic benefits to the state” (Deal, 1975). To top it all off, the refinery was promised to “reduce oil prices in the region, stabilize New England’s supply of oil, and more than triple Durham’s tax benefits” (Deal, 1975). In times of such despair, with the oil embargo, the promises of Onassis and his oil refinery proposal seemed to be the remedy to economic ills plaguing both Durham and the nation.

In a 1974 poll conducted by the Boston Globe, it was determined that 65 percent of New Hampshire voters were in favor of the refinery (Christian Science Monitor, 1974). Within the same article, one fireman from Salem, New Hampshire stated, “I think the ecology freaks are crazy. If Onassis was allowed to build what he wanted it would be clean, create more jobs and relieve the pressure of the energy crisis” (Christian Science Monitor, 1974). The phrase “ecology freaks” revealed a new theme of anti-elitism that I was not expecting to find. As I continued my exploration of newspaper sources, this theme of anti-elitism became part of my focus.

The Proponents vs. Opponents

Tommy Thompson, often viewed as the face of the proponents’ side, was the leader of “Save Our Refinery,” a movement counter to that of Save Our Shores. In a letter to Publick Occurrences, Tommy reported that he was one of many generations of Thompsons who had grown crops and raised dairy herds since the early 1700s on the family’s 300-acre land in Durham. However, in 1969, Thompson’s house, barn, and 55 head of cattle were destroyed in a fire, the loss being too great to rebuild. The only way of life Tommy had known was gone.

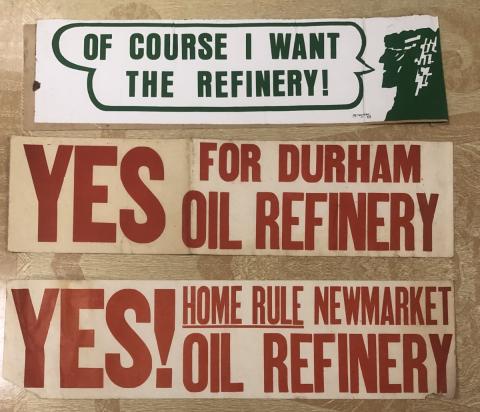

Bumper stickers from the time period showing their support for the refinery. Photo courtesy of New Market Historical Society.

At the same time, the growth of UNH brought with it a growing population and a changing economy. Thompson disliked the growth of Durham, the influence of the university, the migration of new families, and the loss of control to newcomers. The town Thompson once loved was now, in his eyes, turning into a town “only for the rich,” with associated expenses and “prestige” rising due to such growth. He believed that a lack of oil, coal, and steel in the area had made it more expensive to live in, and that an oil refinery in Durham would drive land values and wages up, and taxes down, making it easier for him to sell his now barren land (Why A Farmer Wants A Refinery in Publick Occurrences, 1974).

In a separate letter, Thompson discussed how every town in the area was encouraging business to move in, whether that be shopping centers, highways or, inevitably, in his eyes, oil tankers. Per Thompson, a town such as Durham, which was mostly a residential community with high taxes and difficulty in providing the necessary services, needed an industry, unlike UNH, that would pay taxes to help curb expenses in the town. He noted that more refineries were being planned along the coast of Maine by numerous companies, and problems associated with this industrialization such as new homes, heavier traffic, less wilderness and open spaces, ships on the coastline, and planes overhead would impact Durham. Tommy asked, “How would you like to have all of the problems and none of the benefits?” as “that could happen if Olympic Refineries moves to another location.” Tommy ended his letter with, “Wake up Durham, this is the 20th century” (Wake Up Durham in Publick Occurrences, 1974).

Political cartoon depicting Governor Meldrim Thomson as Santa Claus giving Durham an oil refinery for the Christmas holiday. Photo courtesy of Milne Special Collections.

Supporting the economic aspects of the Onassis refinery, Michael Durgin also saw the benefits, claiming that it would help boost the economy of New Hampshire and bring more fuel (Sees Benefits in The New Hampshire Times). In another letter, the Gage family furthered Durgin’s point, emphasizing that it was the responsibility of New Hampshire citizens to maintain a strong economy for both the state and the country “regardless of ecology” (Favors Refinery in The New Hampshire Times).

I once again noticed sentiments of anti-elitism arising amongst proponents of the refinery, particularly against those associated with the university, in a letter written by proponent Lloyd Varney Jr., who criticized the “so-called educated intellectuals” for speaking for the “ordinary working person.” Varney Jr. continued to criticize the educators of Durham and the highly educated, claiming that “all they know is how to look down their long intellectual noses at us poor stupid people who didn’t go to college.” Mr. Varney then applauded the work of the Governor and the publisher of the Manchester Union Leader for their pro-refinery efforts, saying “more power to the stupid working people, who pay those professors’ salaries” (Start “Where It’s At” in Manchester Union Leader, 1974).

These trends of anti-elitism are continued with E.O Foss, another resident and proponent, who claimed that some of the vote for the refinery would be done as a “protest against the arrogant and presumptive remarks of some ‘intellectuals,’ most of them connected to UNH” (Intellectual Arrogance in Publick Occurrences, 1974). It is evident, through the letters of some Durham residents, there was resentment against UNH among non-university residents, who viewed the university as a detriment.

A Symbolic Vote

In March of 1974, the refinery construction was rejected by a symbolic vote in Durham, despite the previously mentioned Boston Globe poll that stated 65 percent of New Hampshire residents were in favor of the refinery. In a landslide, the vote was “1,254 against and 144 in favor” (Moore, 2018). In addition to the aforementioned efforts of Dudley, Bennett, and Sandberg, the uniqueness of New Hampshire’s government, specifically home rule, played a significant role in the defeat of the industry. This distinctly New Hampshire process of home rule, which is a “municipality’s ability to govern itself,” allowed the opponents to rely on the argument that “no town should be forced to accept an oil refinery unless the people wanted it” (Fillmore, 2020; Moore, 25).

As reflected in the actions of the activist SOS group, people who did not want the refinery refused to accept it. SOS relied heavily on the “rhetoric of citizenship” as they “encouraged people on the Seacoast to use town meetings as a way to influence local issues and to advocate at the state level through their local legislators” (Jarvis, 2020). SOS was able to benefit from its membership demographic, with most members being white, middle-class, and highly educated, who could dedicate time towards the cause (Jarvis, 2020). This is not true of all communities facing environmental hazards, showing Durham’s ability to fight off industry better than others. This speaks to the wider point made by Hurley in his work, in which he discusses the perceptions of scholars and contemporary observers that the “mainstream environmental movement spoke most directly to the needs and aspirations of white affluent Americans” (Hurley, 1995). The needs of the opponents were fulfilled given their success in fighting off the refinery.

Conclusion

I went into this research project with preconceived notions that economic purposes were the primary driver behind the refinery proponents’ beliefs and opinions. It was surprising to discover that anti-elitism played a significant role in shaping the proponents’ beliefs, widely evident in the submissions to regional newspapers. Divisions over environmental concern and politics created bitterness in the country, as they still do today. Historian Jefferson Cowie emphasizes the anger of working-class Americans which can be seen in the language some of the proponents used to describe refinery opponents in their letters to local newspapers (Cowie, 2010). Such language includes insults such as “ecology nuts,” “noisy minority,” “hair-triggered environmentalists,” “ecology freaks,” “ecology mad people,” and “pseudo-educated jackasses.”

While some may have used this anti-elitism as their main reason for voting in favor of the refinery, others used it as a weapon to move undecided people over to the proponents’ side and undercut the opponents. The proponents used their anti-elitism to frame the refinery issue and establish victims of the situation: refinery or face economic despair. Many of the tactics and ideas would sound familiar in this decade, particularly in the context of Donald Trump’s presidential term and campaigns, where his “us-against-them positioning” has suggested that the refinery dispute was not unique (Decker, 2017). Regardless of whether perceived elitism rings true, analyzing different opinions and views allows one to better understand the differing social, economic, environmental, and cultural influences that shape people’s opinions on issues facing their community.

Conducting my own research project transformed my life. My love for research, which grew as I spent toasty summer days in the cooled basement of Dimond Library, inspired me to complete a second research project over the summer of 2022. It also gave me a glimpse of life in graduate school, a path in life I had no idea I could take prior to the McNair Scholars Program as a first-generation college student. Conducting this research project, as dramatic as it sounds, changed the trajectory of my life, and helped me gain my own voice as I sought to amplify the voices of others.

First and foremost, I would like to thank Dr. Dorsey for introducing me to this project and helping me throughout the course of the summer and beyond, both with research and real-world advice. His impact on my undergraduate experience is incalculable. Further, Dr. Kimberly Alexander and John Carmichael of the Newmarket Historical Society were influential in developing my work by providing access to additional archives. I am grateful for the unconditional support and guidance of Tammy Gewehr, Selina Choate, and Dr. Catherine Moran of the McNair Scholars Program, as well as for my fellow McNair Scholars of the summer 2021 cohort, especially Tori Schofield, who can be credited with always keeping me level-headed and being willing to provide feedback. Lastly, the project would not be possible without the funding of the Ronald E. McNair Post-Baccalaureate Achievement Program, to which I owe my future.

References

Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac: And Sketches Here and There, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1949).

Andrew Hurley, Environmental Inequalities: Class, Race, and Industrial Pollution in Gary, Indiana, 1945-1980, (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1995).

Bruce Schulman, The Seventies: The Great Shift In American Culture, Society, And Politics, (Boston: Da Capo Press, 2001), pp. 4.

Cathleen Decker, Analysis: Trump’s war against elites and expertise, (Los Angeles: Los Angeles Times, 2017), https://www.latimes.com/politics/la-na-pol-trump-elites-20170725story.html.

C. Christine Fillmore, Home Rule: Do New Hampshire Towns and Cities Have It?, (Concord: New Hampshire Municipal Association, 2010), pp. 1.

David T. Deal, The Durham Controversy: Energy Facility Siting and the Land Use Planning and Control Process, (Natural Resources Lawyer, 1975), 8(3), pp. 437-453.

David W. Moore, Small Town, Big Oil: The Untold Story of the Women Who Took on the Richest Man in the World—And Won, (New York: Diversion Books, 2018).

Favors Refinery written by Gage Family in The New Hampshire Times, Folder 14, Box 2, Save Our Shores Papers, 1973-2001, MC 69, Milne Special Collections and Archives, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, NH, USA

Ian Lenahan, How Dudley Dudley, Seacoast woman stopped $600M oil refinery in Durham almost 50 years ago, (Portsmouth: The Portsmouth Herald, 2022), https://www.seacoastonline.com/story/news/local/2022/05/21/dudley-dudley-seacoast-women-stopped-600-m-oil-refinery/9650250002/

Intellectual Arrogance written by E.O. Foss in Publick Occurrences, dated January 4, 1974, Folder 7, Box 3, Save Our Shores Papers, 1973-2001, MC 69, Milne Special Collections and Archives, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, NH, USA

Jefferson Cowie, Stayin Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class, (New York: The New Press, 2010).

Joe Stork, Oil and the International Crisis, (Tacoma: MERIP Reports, 1974), pp. 3-34.

Kimberly Jarvis, From the Mountains to the Sea: Protecting Nature in Postwar New Hampshire, (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2020), pp. 106.

Let’s Not Bury Heads written by Jeanne Filion in Publick Occurrences, dated April 5, 1974, Newmarket Historical Society, Newmarket, NH, USA.

Michael Corbett, Oil Shock of 1973-74, (Federal Reserve History, 2013). New Hampshire Employment Security, Community Profiles: Durham, NH, (Concord: Economic and Labor Market Information Bureau, 2021), https://www.nhes.nh.gov/elmi/products/cp/profiles-htm/durham.htm.

Out With The Migrants written by Beatrice P. Walker in Publick Occurrences, dated from April 5, 1974, Newmarket Historical Society, Newmarket, NH, USA

Sees Benefits written by Michael Durgin in The New Hampshire Times, Folder 14, Box 2, Save Our Shores Papers, 1973-2001, MC 69, Milne Special Collections and Archives, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, NH, USA

Start ‘Where It’s At’ written by Lloyd Varey,Jr. in Manchester Union Leader, dated March 4, 1974, Folder 13, Box 2, Save Our Shores Papers, 1973-2001,MC 69, Milne Special Collections and Archives, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, NH, USA

Thomson Unfazed by Vote in Durham in The Portsmouth Herald, Folder 4, Box 3, Save Our Shores Papers, 1973-2001, MC 69, Milne Special Collections and Archives, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, NH, USA.

True Colors Shown written by Edward W. Tourigny in response to Bert Keimach in Foster’s Daily Democrat, dated April 23, 1974, Newmarket Historical Society, Newmarket, NH, USA.

Wake Up Durham written by Tommy Thompson in Publick Occurrences, dated January 11, 1974, Newmarket Historical Society, Newmarket, NH, USA

Why A Farmer Wants A Refinery in Publick Occurrences, dated January 4, 1974, Folder 7, Box 3, Save Our Shores Papers, 1973-2001, MC 69, Milne Special Collections and Archives, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, NH, USA

65% Support Oil Refinery at Durham Supplement from Boston Globe in Christian Science Monitor, dated March 4, 1974, Folder 6, Box 2, Save Our Shores Papers, 1973-2001, MC 69, Milne Special Collections and Archives, University of New Hampshire Library, Durham, NH, USA

Author and Mentor Bios

Samantha DiNatale will graduate in spring 2023 with both a bachelor of science in environmental conservation and sustainability and a bachelor of arts in history. Originally from Haverhill, Massachusetts, Samantha took the opportunity to learn more about Durham’s history and combined her scholarly interests to conduct an environmental history project with the mentorship of Professor Kurk Dorsey and funding from the McNair Scholars Program. A first-generation college student, Samantha has established herself as a historian by designing her own research project, conducting archival research, and collaborating with regional historians to bring under-recognized voices in the refinery debate to the surface. After graduation, she plans to pursue a master's degree in geography and environmental systems at the University of Maryland at Baltimore County as a part of the Interdisciplinary Consortium for Applied Research in the Environment, which seeks to broaden community participation in environmental science and social justice.

Dr. Kurk Dorsey is chair of the history department at UNH and began working at UNH in 1994, specializing in US Foreign policy and environmental history. Dr. Dorsey was drawn to mentoring Samantha as they had both combined the sciences and humanities during their undergraduate careers. Samantha’s research has changed the way Dr. Dorsey teaches the history of the refinery project proposal in Durham, New Hampshire. While it’s easy to look back and celebrate the Durham community’s fight against the project, more context is needed to understand the other side–those in support of the project. Along with digging up great primary sources, including bumper stickers, Samantha’s research shows how the refinery battle fit into larger patterns from the 1970s about government power, economics, and environmental protection. Dr. Dorsey enjoyed working with Samantha and finds the process of writing and publishing for Inquiry to be a useful step for undergraduate scholars to develop their skills in communicating to a general audience.

Copyright 2023, Samantha DiNatale