Yemen, a small nation at the southern tip of the Arabian peninsula, has been mired in political strife and unrest since its government was overthrown in 2014 by the Houthis, a minority Shiite tribal group. Soon after, foreign intervention began, with Saudi Arabia joining the fight alongside the remains of the Yemen government authorities against the Houthis. In 2015, Iran began supporting their ally the Houthis with economic aid and materials, but not with direct military involvement. What ensued has been labeled one of the worst modern-day humanitarian crises, and it rages on to this day.

The author, Bryn Lauer

With no end to the conflict in sight, Yemen now has the status of a failed state, one with no governmental authority or rule of law. This humanitarian tragedy raises many unanswered questions about the effects of foreign intervention on failed states: Why has Yemen’s civil war continued? Why is Saudi Arabia siding with a country lacking a working government? What does Iran have to gain by allying with the Houthis, and why hasn’t it intervened directly? Has Yemen as a failed state exacerbated the conflict? What is at stake for each actor?

The use of the term failed state is debated by political science researchers. Definitions of the term range from complete anarchy to a functioning government with weak institutions. In this article I use the term failed state for two reasons: (1) it places greater emphasis on the system of governance as a path to civil war than on extremism and terrorism (Cordesman and Molot, 2019), and (2) it has been used explicitly as justification for intervention by Saudi Arabia. I use political scientist Robert Rotberg’s commonly accepted definition of a failed state: a state which is unable to provide political goods to its inhabitants and experiences high levels of internal violence (Rotberg, 2003). My project aims to shed light on the dynamic between failed states and foreign intervention, with Yemen as a case study. I became interested in this subject because of an international politics course I took at SUNY Binghamton and have followed Yemen closely since then. After transferring to the University of New Hampshire (UNH) and completing an internship at the Department of State in the Office of Investment Affairs, I received an Undergraduate Research Award, with Dr. Elizabeth Carter as my faculty mentor, and turned my interest into a concrete research project.

Background

Summarizing Yemen’s history over the past several decades remains a challenge, which is why I focus on the key events in this background section. Yemen’s conflict is multifaceted, with regional and domestic actors at play, a history of governmental instability, economic constraints, political fallout, and strained alliances.

The Houthis make up 5 to 10 percent of the population in Yemen. Although a revolutionary Shiite Muslim group, the Houthis’ plight began as a political one during the rule of Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh from 1978 to 2011 (Haykel, 2021). For years, authoritarian President Saleh used corruption and oppression to unify the government and to repress dissent. The Houthis’ goal was to assert themselves as a dominant political group to bring an end to political marginalization and discrimination. These sentiments then cultivated six wars between the Houthis and the central government from 2004 to 2010. In 2011, President Saleh resigned because of mounting tension among supporters and was replaced by Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi, but Hadi’s leadership lasted only three years and included unsuccessful attempts at reform before the Houthis seized Sana’a, the highly populated capital of Yemen, thereby waging war once again on the government of Yemen. With no true foundation in place, Yemen’s government fell swiftly by January 2015, when President Hadi and other politicians were forced to resign. President Hadi fled to Saudi Arabia. Yemen’s sovereignty became porous, the remaining domestic institutions ceased to operate, and foreign actors have had free rein to exert their influence over the region since 2015.

On March 26, 2015, shortly after the Houthis overthrew Hadi’s government, Saudi Arabia launched its first military involvement in Yemen with Operation Decisive Storm, and air strikes, ground troops, and economic sanctions were deployed almost immediately (Nußberger, 2017; Gunaratne, 2018). The launch of Operation Decisive Storm in 2015 was Saudi Arabia’s first deviation from its norm of unassertive foreign policy toward Yemen (Stenslie, 2013). Saudi Arabia justified its active, open military engagement with Yemen by claiming it was countering Iranian influence while defending itself against fallout from a failed state.

Airstrike by Saudi Arabia in Sana’a, Yemen, 2015. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Throughout the fighting, Saudi Arabia and many prominent Western scholars have accused Iran of supporting the Houthis. Iran has historically kept a limited role in Yemeni affairs and did not become an active ally of the Houthis until Saudi Arabia’s direct involvement in 2015. However, during the 2011 Arab Spring uprisings, which were a series of anti-government protests that ricocheted throughout the Middle East, Iran had provided limited aid to the Houthis. The Houthis are not dependent on Iran and are not under their direct control (Vatanka, 2015; Milani, 2015). Nonetheless, Iran has increasingly provided more arms to the Houthis as a direct response to escalation in fighting from Saudi coalition forces (Nichols and Landay, 2021).

As of spring 2022, the conflict is continuing to escalate, United Nations mediation attempts have repeatedly failed, and there remains no internationally recognized government in place (Aljazeera, 2022; Reuters, 2022). As of 2022, 24 million Yemenis need assistance, 100,000 Yemenis have been killed since the start of the conflict in 2015, and 4 million remain displaced (Global Conflict Tracker, 2022).

Martin Griffiths, a UN Special Envoy to Yemen who has attempted diplomacy between the Yemeni and Houthi factions, noted that the crisis in Yemen is man-made, and that ending the war is a choice. Yet Mr. Griffiths, and others in the international community who support this premise, fail to specify exactly what allowed Yemen’s crisis to become man-made in the first place. I was interested in researching the reasons behind foreign interference in a failed state because, intuitively, intervention should be a means to end a conflict. In Yemen, the conflict has only been exacerbated, and I wanted to know what went wrong and why.

Methods

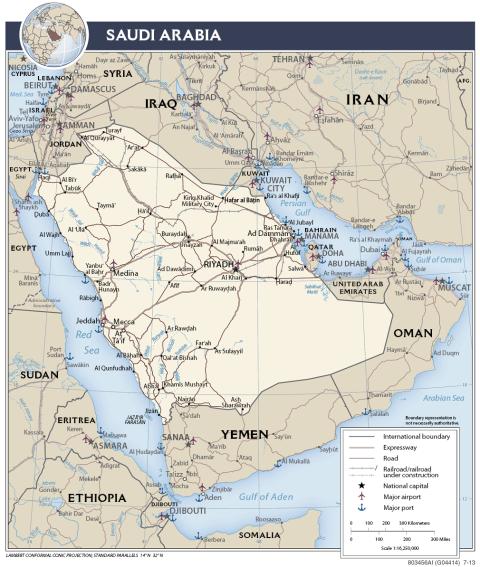

This map shows Yemen in relation to Saudi Arabia, Iran, and other regional countries. Source: Wikimedia Commons

To uncover why regional foreign actors interfere in failed states—specifically, Yemen—I planned several phases of research, each of which would take several weeks. First, I planned to look at when and how Yemen became a failed state, including its weaknesses, when and why each foreign and domestic actor intervened, and the overall geopolitical and societal trends of each actor. Next, I planned to examine empirical evidence from the start of the conflict in 2014 to the present, including military data, domestic and economic data, and peace data. For the final weeks of my research time, I planned to compile theories about the motives of Saudi Arabia, the Houthis, and Iran. This was done via literature review, whereby I examined the rhetoric of each actor toward Yemen and looked at the contemporary policies and overall belief system of each actor. I planned to conclude my research time by drawing conclusions and drafting an argument that would address my research goal. All research was conducted remotely using sources accessible online.

I used a variety of sources over the course of my research, including both political science and history journal articles. For empirical evidence, I relied upon data collected from the World Bank, the Yemen Data Project and Civilian Impact Monitoring Project, as well as online articles from MediaWire, Reuters, and Al Jazeera. Specifically, I collected data on the change in Saudi military expenditures, civilian casualties, coalition air raids, political violence, unemployment, government institutions, rule of law, markets, poverty, GDP, supply chains, migration flows, and peace attempts before and during the war. This data was critical, as it allowed me to quantify the potential impact of interference on factors relating to violence, political stability, and economics in a failed state—specifically, Yemen.

I adapted my research plan on numerous occasions. Most of my research was composed of searching the history of Yemen, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the Houthis on EBSCOHost. From there, I selected data on the conflict and pieced together an argument. When I needed to fill in gaps, I searched news articles. My research was nonlinear, because the ideas grew as I went along, thereby causing me to deviate from my original plan as needed.

Results: Three Opportunities

My research suggests that foreign actors may perceive the cost of intervening in a failed state—a space devoid of authority—as low and therefore simply too good an opportunity to pass up to influence regional power. In pursuing opportunities to intervene in a failed state, foreign actors may exacerbate the conflict and plunge the state into chronic instability. After concluding my research, including my review of the articles and databases mentioned in my methods section, I argue that failed states create three opportunities for actors who intervene.

The first is the Opportunity for Security, in which foreign actors may perceive failed states to be security threats to their own inhabitants and to neighboring countries. Therefore, actors looking to gain favor domestically and regionally may claim to intervene to defend the inhabitants of the failed state while protecting themselves from regional spillover.

The second is the Opportunity for Influence. Because failed states are unable to defend themselves militarily and are unable to pursue diplomatic measures, foreign actors perceive intervention as low risk, and victorious foreign actors gain the opportunity of influencing the restructuring of the government of the failed state in their favor.

The third is the Opportunity for Amplifying Power, in which actors who intervene can amplify their regional power by securing a swift victory at a low cost.

Saudi Arabia: Opportunity for Amplifying Power

With its intervention in the conflict in Yemen, Saudi Arabia claims to pursue the Opportunity for Security, but the reality shows that it pursues the Opportunity for Amplifying Power. Despite claiming to defend the Yemeni people and restore the Hadi government, the extent and intensity of Saudi Arabia’s military efforts, their unwillingness to cooperate in peace talks with the Houthis and other actors or abide by ceasefires, their blocking of food and medicinal imports, and deliberate attacks on civilian infrastructure such as hospitals indicate they are uninterested in the well-being of Yemen’s inhabitants and its stability. Actors insecure in regional power likely pursue more aggressive intervention as a desperate attempt to amplify their regional status. Saudi Arabia’s regional power status has been waning since 2014, driven largely by their dwindling oil reserves and unsuccessful interventions in Iraq after 2003 and Lebanon in 2008 (Council, 2011), which evidences their motivation behind intervention.

As mentioned previously, Saudi Arabia has not acted in a way that suggests it is concerned with a strong Yemeni state, and especially not one as an ally. Driving Yemen into further instability has created a breeding ground for terrorism, illegal immigration, and regional spillover. Under the guise that it is pursuing the Opportunity for Security, Saudi Arabia has been able to justify its intervention as countering Iranian influence while defending itself against fallout from a failed state. In reality, Saudi Arabia’s intentions extend further than self-defense. By pursuing the Opportunity for Amplifying Power, Saudi Arabia has supported an illegitimate government, destroyed critical infrastructure, killed innocent civilians, refused to accept anything other than complete victory over the Houthis, and blocked imports, thereby guaranteeing Yemen’s instability for years to come.

Iran: Opportunity for Influence

Iran’s intervention in Yemen suggests that it is pursuing the Opportunity for Influence. In contrast with Saudi Arabia, Iran is more stable in regional power. This is evidenced by Iran’s national sovereignty and fierce independence, and that it aligns itself with “Neither East nor West” (Maloney, 2017). Stable actors do not seek to use failed states to boost their status and can instead pursue opportunities related to “soft power”—building support domestically and regionally through positive attraction and persuasion (Nye, 1990). Iran seeks to align itself with marginalized groups—in the case of Yemen, the Houthis—to gain in soft power by being viewed as a “champion of the oppressed and marginalized” (Juneau, 2016). This is the same strategy Iran applied in Iraq and Afghanistan, where it exerted soft power through reconstruction aid, infrastructure development, media, and financial investments (Wehrey et al., 2009).

Rather than engage militarily in Yemen, Iran has supported the Houthis from a safe distance. During the 2011 Arab Spring uprisings, Iran provided limited aid to the group. By the time the Yemeni government was overthrown in 2014, Iran supplied some arms and economic support to the Houthis, and as of 2022 it continues to keep its distance (IISS, 2019). Iran’s goal is to establish ties to the Houthis should they secure victory and restructure the government. Although Iran does not directly seek to state-build in Yemen, the opportunity to maintain a steady presence with the Houthis has been low-cost and low-risk.

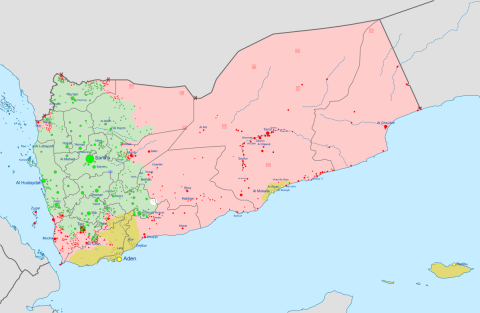

Map of the Yemeni civil war and Saudi Arabian intervention as of 2021. Red is controlled by the Hadi-led government; green is Houthi controlled; and yellow is controlled by the Southern Transitional Council, a secessionist organization in southern Yemen. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Current Situation

As of January 2022, the war continues to drag on, despite Saudi Arabia’s expectation of a quick and decisive victory. Both Saudi Arabia and the Houthis are intensifying their efforts, and Iran continues to steadily support the Houthis with arms. To complicate the situation even further, the United Arab Emirates, which has been part of Saudi Arabia’s coalition since 2015, has shown signs of increasing its role in the conflict for its own ends. All this means that peace is still far out of reach. For years, Saudi officials promised that progress was being made in their fight. Instead, Saudi Arabia finds itself struggling to exit Yemen, which has further exemplified its deteriorating regional power. It is likely that Saudi Arabia overestimated its military prowess and strategy. By using a “blank check” strategy for fighting the Houthis, Saudi Arabia has demonstrated its lack of understanding of the conflict (Horton, 2020). When compared with the fractured and weakly governed Yemeni army supported by Saudi Arabia, the Houthis have repeatedly been successful against coalition forces by striking fast and staying mobile, and, according to some Western experts, are poised to defeat the coalition forces despite the odds (Horton, 2020).

Conclusion

If a peace settlement is reached through Saudi Arabia and Iran brokering a peace agreement between the Houthi and Hadi regimes, the question remains: What is to prevent intervention from occurring every time an internal conflict arises? If Yemen and other failed states experience conflicts via revolution or civil war, what can prevent external actors from intervening? As this research has demonstrated, the incentive to intervene in failed states is a powerful one. Reworking a state’s entire structure of government is complex, and there is no one-size-fits-all.

Given that Saudi Arabia sought to amplify its power, its inability to conquer an easy target will be a major blow to its regional power status. If Iran is to cease support, it is likely that the Houthis would be capable of surviving on their own. Having sought gains in soft power, Iran will not lose out as extensively. Regardless, the real loser at the end of the conflict will be Yemen. The real calamity is that unchecked intervention has degraded the state and created further conflict. Under the guise of championing the oppressed, Saudi Arabia, the Houthis, and Iran have all made for a grave future for Yemen. I hope that readers will see through the layers of complexity of the Yemen conflict and better understand why foreign intervention can be dangerous and costly.

By studying the conflict in Yemen so deeply, I have garnered a greater appreciation for research in international politics. I underestimated how in-depth and complex the research process is. Most importantly, I have learned that research is not rigid; it morphs and grows with each new discovery, and often more questions arise than answers. Because of this research, I now think about the world in terms of opportunities and incentives, on the global and personal level. My next goal is to apply the ideas that I theorized in this project to an exploration of international politics from a financial incentive perspective. This perspective is important to include in the research of world affairs, because, more often than not, money is at the heart of conflicts. After graduation, I hope to follow my passion for researching international conflict and to publish more of my writing on the subject.

Thank you to Mr. Dana Hamel, who made this research possible through a generous endowment, as well as the Hamel Center for Undergraduate Research staff. Dr. Elizabeth Carter, thank you for inspiring me to pursue international politics research in your United States in World Affairs class. I am incredibly grateful for the opportunity to complete this project and for those who helped me along this journey.

References

Allinson, Tom. (2019). Yemen’s Houthi rebels: Who are they and what do they want? DW: 01.10.2019. www.dw.com/en/yemens-houthi-rebels-who-are-they-and-what-do-they-want/a-50667558.

Al Jazeera. (2022). How the Yemen conflict flare-up affects its humanitarian crisis. https:/www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/1/18/yemens-humanitarian-crisis-at-a-glance.

Council on Foreign Relations Press. (2011). Saudi Arabia in the new Middle East. https://www.cfr.org/report/saudi-arabia-new-middle-east.

Cordesman, A., and Molot, M. (2019). Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Libya, and Yemen: The long-term civil challenges and host country threats from “failed state” wars. Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). https://www.csis.org/analysis/afghanistan-iraq-syria-libya-and-yemen.

Global Conflict Tracker. (2022, March 11). War in Yemen. https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/war-yemen.

Gunaratne, R., and Johnsen, G. (2018). When did the war in Yemen begin? https://www.lawfareblog.com/when-did-war-yemen-begin.

Haykel, B. (2021). The Houthis, Saudi Arabia and the war in Yemen. https://www.hoover.org/research/houthis-saudi-arabia-and-war-yemen.

Hodali, D. (2021). “Saudi Arabia has lost the war in Yemen.” https://www.dw.com/en/saudi-arabia-has-lost-the-war-in-yemen/a-57007568.

Horton, M. (2020). Hot issue—the Houthi art of war: Why they keep winning in Yemen. https://jamestown.org/program/hot-issue-the-houthi-art-of-war-why-they-keep-winning-in-yemen/.

IISS (2019). Chapter five: Yemen. Iran’s networks of influence in the Middle East. Routledge. https://www.iiss.org/publications/strategic-dossiers/iran-dossier.

Juneau, T. (2016). Iran’s policy towards the Houthis in Yemen: A limited return on a modest investment. International Affairs, 92(3), 648.

Maloney, S. (2017). The roots and evolution of Iran’s regional strategy. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/the-roots-drivers-and-evolution-of-iran-s-regional-strategy/.

Milani, M. (2015, April 19). Iran’s game in Yemen: Why Tehran isn’t to blame for the civil war. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/iran/2015-04-19/irans-game-yemen.

Nichols, M., and Landay, J. (2021). Iran provides Yemen’s Houthis “lethal” support, U.S. official says. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security-usa-idUSKBN2C82H1.

Nußberger, B. (2017). Military strikes in Yemen in 2015: Intervention by invitation and self-defence in the course of Yemen’s “model transitional process.” Journal on the Use of Force and International Law, 4(1), 110–160.

Nye, J. S. (1990). Soft power. Foreign Policy, 80, 153–171. https://doi.org/10.2307/1148580.

Reuters. (2022, January 21). U.N. chief condemns deadly Saudi-led coalition strike in Yemen. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/several-killed-air-strike-detention-centre-yemens-saada-reuters-witness-2022-01-21/.

Rotberg, R. (2016). Failed states, collapsed states, weak states: Causes and indicators. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/statefailureandstateweaknessinatimeofterror_chapter.pdf.

Stenslie, S. (2013). Not too strong, not too weak: Saudi Arabia’s policy towards Yemen. Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Centre. https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/162439/87736bc4da8b0e482f9492e6e8baacaf.pdf.

Wehrey, F., et al. (2009). Assertiveness and caution in Iranian strategic culture. In Dangerous but not omnipotent: Exploring the reach and limitations of Iranian power in the Middle East (pp. 7–38). Rand Corporation.

Vatanka, A. (2014). Iran, Saudi Arabia find common ground in Yemen. https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2014/11/iran-yemen-saudi-arabia-houthi-islah.html.

Author and Mentor Bios

Bryn Lauer will graduate from the University of New Hampshire in spring 2022 with a bachelor of science degree in business administration: finance. She hopes to pursue work as a financial economist with a concentration in international affairs. Originally from Durham, New Hampshire, Bryn became interested in international conflict after taking some international politics classes and participating in an internship at the U.S. Department of State. Because of Yemen’s unique position as a failed state, Bryn wanted to understand the motivations of outside actors intervening and how their actions impacted the conflict there. To pursue her research interests, Bryn received an Undergraduate Research Award through the Hamel Center for Undergraduate Research. From the project Bryn gained a deep understanding of the history of Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the Houthis, as well as learned a lot about the research process itself. Given the circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic, Bryn unfortunately was unable to conduct field research abroad, so she had to rely only on information that was published in databases. This presented a challenge for Bryn, because she had to be able to work through contradicting data to find information that focused specifically on the effects of external intervention of foreign states. Despite the challenges, Bryn was able to piece together the data, history, and geopolitics to develop her own theories, making the research her own.

Elizabeth Carter has been an assistant professor of political science at the University of New Hampshire since 2015. She specializes in comparative politics, political economy, and Western European politics. Dr. Carter met Bryn in her U.S. and World Affairs course and was delighted to serve as her research mentor after being impressed with an essay on Yemen that Bryn had written for the class. Though she has mentored several undergraduate students for both undergraduate honors theses and as part of Hamel Center Undergraduate Research Awards, this was Dr. Carter’s first time mentoring a student who submitted an article to Inquiry. Dr. Carter is proud of the great work that Bryn conducted. In addition, Dr. Carter says that it was wonderful to have the experience of enhancing her understanding of a region, like Yemen, that she had not researched much herself, especially with the rigorous research and applications of political science theories and framework that Bryn incorporated into her work. Dr. Carter believes that it’s important for researchers to make research more accessible to broader audiences across multiple disciplines, not just to those engaged in that particular field.

Copyright 2022, Bryn Lauer