When I received the exciting news that I would spend the summer of 2021 studying composting, I did not expect to be working with numbers and spreadsheets. Instead of examining how food scraps decompose into soil, I found myself deep in the weeds of local policy. Because of the online nature of my research during COVID-19, field trips to observe composting methods up close didn’t exist, so my goal was to develop a better understanding of community policies and individual behaviors regarding food waste—and the potential for improving both. Investigations such as this aim to expose inefficiencies to make systems more cost-effective, easier to use, and better for the environment.

The author, Chloe Gross

As an environmental conservation and sustainability major, I am interested in how changing our global food system can create positive impacts for the climate and for social justice. My Research Experience Apprenticeship Program (REAP) project brought me into the world of organics waste management with Jennifer Andrews at the University of New Hampshire (UNH) Sustainability Institute. I worked closely with the Regional Compost Working Group (RCWG), made up of representatives from the Towns of Lee and Durham, NH, the Oyster River Cooperative School District (ORCSD), and the University of New Hampshire. These entities have existing individual organic waste solutions and convened in part to investigate whether a collaborative plan would lead to increased efficiency, accessibility, and participation. My goal was to gather and analyze important information that would guide recommendations for the entities to decrease their waste footprint.

Food Waste and Its Consequences

Food waste is an unnecessary tragedy. While 1 in 8 Americans are food insecure, 40% of US food is uneaten (National Resources Defense Fund, 2021; Gunders, 2017). Food waste includes kitchen scraps, uneaten leftovers, and unsold groceries that end up in the trash (Thyberg and Tonjes, 2016). Food loss encompasses crops left in the field, discarded food in warehouses and processing centers, and other items that do not make it through transport to market (Thyberg and Tonjes, 2016).

Discarded food at all levels contributes to the overuse of fertilizers and excess release of other substances like nitrogen into the environment (Hall, 2009). Any food not eaten wastes valuable and finite resources, so decreasing food waste overall is integral to living sustainably on Earth (Hall, 2009). Beyond wasting resources, landfilled food waste is a disaster for the Earth’s climate because it creates methane, a greenhouse gas that is much more potent than carbon dioxide (National Resources Defense Fund, 2021). Landfills account for one-third of all US greenhouse gas emissions. If the world’s food waste was a country, it would be the third-highest emitter in the world—behind only China and the United States (US Department of Agriculture, 2021; United Nations Environment Programme (n.d.)).

It is necessary to decrease organic waste not only for the climate’s sake but also to ensure that every person has enough to eat. While widespread food loss will be mitigated mostly by systemic changes to the agricultural industry and economy, personal food waste is an issue that individuals can easily address. Meal planning to avoid buying unnecessary groceries and cooking just enough food for one meal are great ways to avoid creating food waste in the first place. Composting kitchen scraps then diverts any unavoidable food waste (Food Print, 2021). Diverting waste not only keeps organic material from entering the landfill but can provide clean energy via anaerobic digestion or replace nutrients in the environment via compost (Environmental Protection Agency, 2021). The global food waste issue will be addressed only when communities take action to decrease their consumption and increase waste diversion practices.

How the Waste Management Hierarchy Plays In

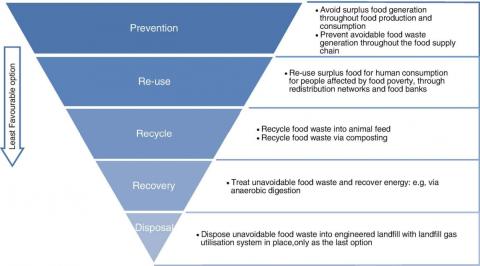

Figure 1: The waste management hierarchy shows the decreasing preferability of waste disposal techniques in relation to how far each is from the primary goals of waste prevention and reduction of global inequalities in waste disposal, especially in marginalized communities (Papargyropoulou et al., 2014).

The waste management hierarchy is a tiered approach to ranking waste management solutions by how favorable they are to the environment and to human health and well-being (Environmental Protection Agency, 2021). Growing concern about the global waste crisis resulted in the development of this concept to provide guidance about the most ideal ways to reduce waste. (Figure 1.) The top four levels of the hierarchy aim to avoid the bottom tier, disposal, with each lower tier describing a less desirable solution than the method above it (Papargyropoulou et al., 2014). Most waste, especially organics, can be dealt with in multiple tiers of the hierarchy to completely avoid disposal.

Critical application of the waste management hierarchy makes sure that all possible uses of products are considered before disposal. By applying the hierarchy to the current systems in place for each of the Regional Compost Working Group’s entities, the group recognized that current systems of organic waste diversion (such as compost and biodigestion, which fall under “recycling and “recovery”) are low on the hierarchy. Since prevention is at the top of the hierarchy, we acknowledged that a public waste reduction education initiative may be a beneficial step toward reducing overall waste. Therefore, as the Working Group brainstormed, we framed our thoughts about potential solutions around what would motivate our communities to reduce consumption and decrease excess waste in the first place.

Importance of an Educational Campaign

As the RCWG’s perspective on waste diversion shifted toward reduction, we realized that a larger issue beyond the composting operations themselves was the public’s awareness of the waste crisis. If community members do not understand why diverting organic waste is an essential aspect of preserving the environment, fighting the climate crisis, and addressing social justice issues, they will not regard a composting program as important, and therefore will not participate (Johnson, 2016). Deepening the public’s understanding of waste issues increases the likelihood of producing successful community composting programs and other waste diversion initiatives (Johnson, 2016). Luckily, various local education initiatives could be integrated into comprehensive waste curriculums, adaptable for each of the entities’ audiences.

Lee’s existing recycling and consumption awareness outreach work could be incorporated into the other entities’ educational programs to ensure that the full scope of waste issues is addressed. ORCSD’s recent participation in a waste audit of the high school could act as an example for other local organizations and businesses, and it may be possible to integrate experienced ORCSD students into a waste audit campaign for the towns. UNH has historical sustainability expertise in running waste diversion programs like Safe Electronic Equipment Disposal (SEED) and Trash2Treasure, as well as composting. This knowledge could be utilized to educate residents on similar waste diversion programs for the towns and school district. Durham’s recent compost tracking and community involvement campaign could also become part of a larger waste education initiative. Experiences from Durham residents could be used as examples for why you should try composting. The region could certainly work together to create a comprehensive and accessible waste education program that would benefit all community members.

Analysis of Survey, Interview, and Existing Information

It is important to note that this region is relatively environmentally conscious, so in terms of community composting programs, the Regional Compost Working Group was not starting from scratch. For several years, the Towns of both Durham and Lee have hired Mr. Fox Composting to haul food waste from drop-off sites in town to its commercial composting facility. The towns have also run waste-reduction challenges and campaigns. ORCSD and UNH also have established food-waste diversion programs: ORCSD contracts with Mr. Fox, and UNH has a long-standing in-house composting program for waste from the dining halls as well as a partnership with Agri-Cycle Energy to divert food waste from other locations on campus.

Given these existing parallel efforts, the goal of the RCWG was to assess the efficiency of existing programs and to investigate potential ways to streamline and collaborate. As we gathered data about each entity’s current waste systems and related costs, we found critical knowledge gaps, particularly pertaining to local businesses’ sustainability practices and perspectives. My main roles were to create, market, and analyze a survey that would fill these gaps; conduct interviews with employees of other towns and composting companies to explore potential solutions; analyze the entities’ historical composting data; and synthesize this information into a report for the RCWG to use when advocating for more sustainable food-waste management.

Survey

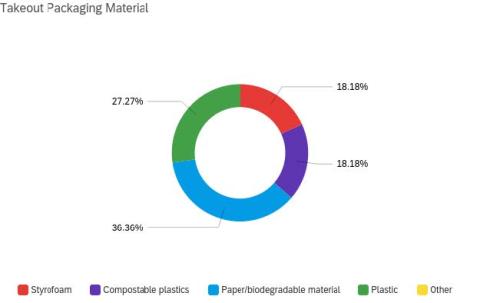

Figure 2: Food-related businesses (restaurants and grocery stores) indicated that they use a variety of takeout packaging materials, including paper/biodegradable materials, plastic, compostable plastics, and Styrofoam.

The initial purpose of the survey was to gather information from Durham and Lee food businesses about their organic waste, recycling, and trash disposal practices. (Figure 2.) As the survey circulated through local groups for approval (including the Durham Integrated Waste Management Advisory Committee and Lee Sustainability Committee), the questions grew from purely food waste related to additional topics such as reusable food-service ware usage, to-go packaging materials, energy and water usage practices, renewable energy perspectives, and general sustainability perspectives. This morphed into a comprehensive Community Sustainability Survey whose data would be used by local municipalities and organizations. I then created survey announcements for the towns’ e-newsletters and flyers to distribute by canvassing local businesses.

Although the purpose of the flyer distribution was not directly for data collection, it did result in some qualitative information. Most canvassed owners and managers, some of whom also completed the survey, seemed enthusiastic about a potential expanded municipal composting program. Multiple business managers said that the town/s would benefit from having an expanded composting program and that their business would participate if the system was easy and/or saved them money. This was highly encouraging and provided a real-life sense of the attitudes of food businesses in the area.

Figure 3: Business owners and managers were asked how important waste reduction practices were to their operations. Out of five points, the mean response was 2.63.

One striking finding from the survey was that business owners considered waste reduction less important than energy and water conservation. (Figure 3.) This suggests that the public lacks awareness of the importance of reducing waste. This

makes sense, as there have been many private and public campaigns as well as general global publicity about water crises and the need to decrease energy consumption because of climate change. There is much less of a spotlight on the global waste crisis (Simmons, 2016). Being conscious of this awareness gap is crucial, because if members of the public does not think that waste diversion is important for social or environmental reasons, they will not value or participate in a composting program. Luckily, 50% of survey respondents expressed interest in receiving more sustainability resources and likewise were interested in composting, so a regional educational campaign could help bridge this gap. The lack of knowledge of the waste crisis, as shown in my research, paired with requests for more sustainability education by local business owners, led the RCWG to determine that a waste education campaign will be a key step toward increasing the public’s participation in the composting programs in addition to fostering a more sustainability-oriented society.

Interviews

Another important part of my research was interviews. I spoke to employees from various local composting and biodigestion companies and to representatives from municipalities that are currently implementing community composting initiatives. These online interviews helped me visualize what kind of community composting models work best for town communities and understand how long these programs take to grow. It was encouraging to see that communities have successfully implemented community composting programs in places similar to Durham, meaning that we too can make a difference in our organic waste management.

My first interviews were with Garbage to Garden, a local composting company based in Maine. These interviews revealed that not all bioplastic is created equal. Only certified compostable bioplastics can be composted at commercial facilities. These plastics must be labeled “compostable”; “biodegradable” is not sufficient, as those materials are still petroleum based and will not break down effectively in composting operations. This is important for businesses and the public to understand so that compostable material does not become contaminated with non-compostable materials. Because multiple businesses in our region use this type of packaging, it is critical that the Working Group’s solutions allow for the easy integration of compostable plastics.

I also interviewed a community planner from Medford, Massachusetts, to gain an understanding of how the city implemented a community composting initiative with Garbage to Garden at a discounted rate, making it more financially accessible to residents and resulting in greatly increased participation. In addition, I interviewed a city councilor of Waterville, Maine, to assess how Waterville, a college town similar to Durham, is melding curbside pickup with a free drop-off site as they launch a partnership with Garbage to Garden.

Volume/Cost Analysis

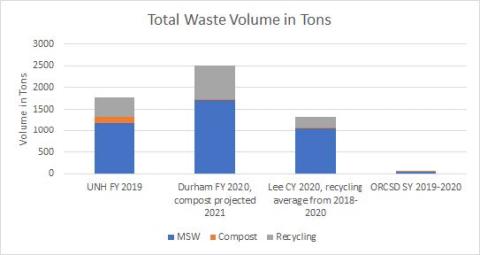

Figure 4: The stacked bar chart shows how the current volumes of municipal solid waste, compost, and recycling waste from each entity compare with each other. Some data points are missing, such as ORCSD’s recycling figures.

Cost data was crucial in exploring solutions, because for all the member entities of the RCWG, waste diversion must cost the same or less than current waste disposal prices to gain community buy-in. Finding and comparing these data points was a critical step in making informed decisions regarding the entities’ waste programs.

To compile all the data, each entity provided figures for total annual volume and cost per ton of compost, municipal solid waste (trash), and recycling disposal. I took this agglomeration of data and made sure the points were accurate and comparable. I then created graphs to visualize the waste volumes and developed presentations to describe the data’s relevance. This work helped identify each group’s individual needs and aided in weighing the pros and cons of organics diversion solutions. (Figure 4.)

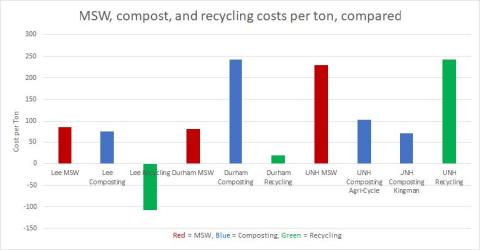

The cost comparisons I created illuminated the differences in what each entity currently pays for its service and the potential for improvements. (Figure 5.) For example, Lee pays only for the volume of compost it actually sends to Mr. Fox, which saves them $9 per ton of waste composted versus landfilled waste.

Figure 5: Comparisons of municipal solid waste, compost, and recycling costs per ton display the discrepancies in cost and potential for savings. Lee earns revenue from selling recycling. There was no cost data available for ORCSD.

Durham, on the other hand, has a fixed rate contract with Mr. Fox, and needs to compost three times its current tonnage (a relatively modest amount) to realize this savings. ORCSD also has a contract with Mr. Fox, but the district has incomplete cost data, making it difficult to identify whether their current contract could be better negotiated. At UNH, the least contaminated compost (from dining halls) is sent to Kingman Farm and the rest is sent to Agri-Cycle, as they are better equipped to handle contamination. Composting at Kingman is roughly the same cost as commercial composting for Durham and Lee, whereas Agri-Cycle is substantially more expensive. That said, it is twice as expensive per ton for UNH to send waste to the landfill than to compost, so diverting organics to decrease the overall volume of trash is highly in UNH’s favor.

Possible Composting Solutions

My interviews and desk research, as well as the RCWG’s discussions, all highlighted that there are multiple ways to address the region’s local composting problems. In Lee and Durham, two distinct parties must be considered when developing a community composting plan: businesses and residents. While it was good to hear through canvassing that many business owners support the idea of community composting, they shared concerns about storing organics for weekly pickup or transportation of organics to a drop-off site at the town’s transfer station. Similarly, ease of access and minimal nuisance are concerns for residents, who may favor weekly curbside pickup versus a drop-off site because their volume of organic waste is smaller. Therefore, ease of use and cost of programs must be addressed if the community is going to support the effort. These needs present an opportunity to provide flexibility.

The RCWG identified that at this point, there are three main options to consider: coordinating a backyard composting initiative, building or expanding a compost facility, or hiring/renegotiating contracts with existing compost vendors. A backyard composting program would mainly consist of distributing educational materials with tips about how to backyard compost. There are myriad backyard composting resources available, so compiling materials for a campaign would not be difficult or costly, and it could be tailored to each entity’s needs. A backyard composting initiative could also be rolled into an educational campaign prior to advertising a town’s contracted plan with a compost hauling service. Although simple and effective for interested homeowners, a backyard composting initiative leaves businesses and apartment residents with no easy way to compost.

Building and operating a new, regional compost facility is another option that was considered by the RCWG. At this time, however, it does not appear to be feasible because of infrastructure, staffing, and cost restrictions, in addition to accessibility issues if the program did not include curbside pickup. When the group started off, there was a suggestion that it might be worthwhile to explore a model in which the entities would collectively fund the expansion of UNH’s Kingman Farm’s operation. However, preliminary exploration highlighted many obstacles, including the reality that the Kingman Farm operation is not equipped to handle compostable plastics, which are a known component of local compostable materials. This presents a problem, because not permitting the incorporation of compostable plastics would likely create confusion and decrease the public’s participation, defeating the purpose of creating or expanding a local facility. Because of these issues, using an existing commercial composting vendor such as Garbage to Garden, Mr. Fox, or Agri-Cycle may be the best solution for the entities.

One approach to this could be to recommend that residents and businesses independently pay for a service that works best for them individually. Or, to increase participation by residents and businesses, entities could work with the service to come up with a plan that would allow each entity to tailor their program to their own specific needs—for example, coordinating drop-off stations at town transfer stations or contracting a discounted rate for those who want a pickup service but not the other benefits many of these vendors offer, such as deliverable compost, which apartment renters likely won’t need. This solution would be minimal work for the region because the logistics would be coordinated by the vendor. Using a service would also be desirable because they can take compostable plastics, unlike the other two solutions.

All of the options presented could combine the needs of the four entities or be separate programs. Each has pros and cons, but after compiling relevant data, I recommend that each of the entities independently explore hiring new compost vendors more appropriate to their needs or renegotiating contracts as a short-term solution.

Reflection

At the beginning of my summer research, I did not understand the complexities of working with multiple groups for a general purpose. The slow-moving tendencies of municipal and nonprofit groups also caused me to reassess my perception of how fast solutions can be implemented. I expected to collect and analyze important data, apply it to the entities’ current situations, make recommendations, and put those changes into action. However, I realized that the issue of community composting on a municipal and organizational level is much more complicated than I initially understood it to be. Although thoroughly investigating all possible routes of action was frustrating for me because it took longer than I expected, it prepared us for obstacles that we may not have been able to efficiently overcome if we had not done our homework. Through this process I cultivated patience as I learned how to categorize and display data, create and analyze a survey, speak to businesses owners and managers about waste practices, and create a comprehensive results document that shows not only local collected data but also global context and applicable solutions. Our hard work paid off, because just over a year after its conception, the Working Group distributed its Final Report and Recommendations document to each entity’s superiors with the intent for it to guide further waste reduction policy and local initiatives. I continued this work throughout fall 2021 as a zero-waste intern at the UNH Sustainability Institute and recently transitioned into the role of the Trash2Treasure student intern. My REAP experience taught me about much more than just composting. I appreciate the opportunity I had to learn not only the ins and outs of community composting, but how to collaborate with multiple kinds of organizations and consider solutions that benefit each individual’s needs.

I would like to thank Jennifer Andrews for her guidance and constant support in this research. Many thanks also to the members of the Regional Compost Working Group for their knowledge, thoughts, and efforts to improve waste practices in our communities, and for all their encouragement and advice while I worked with them. Finally, thank you to my donors, Mr. Dana Hamel, the Class of 1962 Student Enrichment Fund, Mr. John Greene and all those working at the Hamel Center for Undergraduate Research, as without them this research would not have been possible. I am so grateful for this opportunity and all that I learned in the process.

References

Environmental Protection Agency. (2021, January 13). Sustainable management of food basics. https://www.epa.gov/sustainable-management-food/sustainable-management-food-basics

FoodPrint. (2021). The problem of food waste. https://foodprint.org/issues/the-problem-of-food-waste/

Gunders, D. (2017). Wasted: How America is losing up to 40 percent of its food from farm to fork to landfill. https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/wasted-2017-report.pdf

Hall, K. D. (2009, November 25). The progressive increase of food waste in America and its environmental impact. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0007940

Johnson, C. (2016, April 30). How to prevent food waste: 27 steps for community leaders. https://truthout.org/articles/how-to-prevent-food-waste-27-tips-for-community-leaders/

National Resources Defense Fund. (2021). Food waste. https://www.nrdc.org/food-waste

Papargyropoulou, E., Lozano, R., Steinberger, J. K., Wright, N., & bin Ujang, Z. (2014). The food waste hierarchy as a framework for the management of food surplus and food waste. Journal of Cleaner Production, 76, 106–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.04.020

Simmons, A. M. (2016, April 22). The world’s trash crisis, and why many Americans are oblivious. https://www.latimes.com/world/global-development/la-fg-global-trash-20160422-20160421-snap-htmlstory.html

Thyberg, K. L., and Tonjes, D. J. (2016). Drivers of food waste and their implications for sustainable policy development. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 106, 110–123. https://commons.library.stonybrook.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1020&context=techsoc-articles

United Nations Environment Programme (n.d.). Promoting sustainable lifestyles. https://www.unep.org/regions/north-america/regional-initiatives/promoting-sustainable-lifestyles#:~:text=Globally%2C%20if%20food%20waste%20could,3.3%20billion%20tons%20of%20CO2

US Department of Agriculture. (2021, March 16). Why should we care about food waste? https://www.usda.gov/foodlossandwaste/why

Author and Mentor Bios

Chloe Gross is a sophomore from Deerfield, New Hampshire, majoring in environmental conservation and sustainability. She’s a proud Honors student, a Hamel Scholar, and a member of Phi Sigma Biological Honor Society. Through the Research Experience and Apprenticeship Program (REAP), Chloe learned how rewarding it is to work with organizations and municipalities in furthering community sustainability goals, despite how time consuming the research process can be. Performing research remotely due to the pandemic made work less personal, but close collaboration with the Regional Compost Working Group proved valuable and encouraging. She enjoyed analyzing data and presenting conclusions to inform actionable recommendations. Chloe considers her research important and relevant to the local community and wants to raise community awareness of food waste and diversion practices. She plans to attend graduate school and hopes to work in the environmental humanitarian sector, improving people’s lives with nature as part of her toolbox. Chloe is grateful to have gained a fresh perspective on community work and the importance of the research and reporting processes through REAP.

Jennifer Andrews is a project director of the UNH Sustainability Institute. She’s been employed at UNH since 2014, and her role is to coordinate UNH’s efforts to set and achieve goals around climate change, zero waste, and other sustainability challenges, and to share the University’s learnings in support of other organizations around the region. When Chloe Gross approached her about being a mentor, they jumped on a food-waste-focused study together. Andrews has mentored other students in applied research projects in the past, but Chloe is her first Inquiry author mentee. She is grateful for Chloe’s constant practical and action-focused mindset for the duration of the project, and for the valuable data Chloe collected despite the slow pace of the research process and the obstacles presented by the pandemic. Andrews’s experience is that the work of sustainability demands inclusive and effective community engagement, and she therefore believes that students writing for Inquiry must be able to cater to a range of audiences; this in itself builds community.

Copyright 2022, Chloe Gross