Sexuality and Regional Dialects in Southern New Hampshire

The concept of social identity dominates contemporary social and political discourse. We see statistics broken down along the lines of gender, class, race, or sexuality, and hear jokes that have to do with these social identities. While statistics are useful in constructing public policy, and jokes are funny in the right contexts, the way that social identities function is richer and more complex than some popular identity-based discourse may let on. Cultural discourses and stereotypes about the way certain people dress, speak, or otherwise act may not be predictive of how these people behave, but they still inform the ways that people express their identities socially.

Hayden Stinson

However, instead of dictating how people act across the board, identities are played with and are performed differently in different contexts. People may want to up-play or downplay their membership to certain social categories to be perceived in certain ways. If somebody from the South, for example, wanted to up-play their southern identity, they would exaggerate their southern “twang.” On the other hand, if they wanted to downplay their southern identity, they would minimize the twang.

In many cases, someone’s intention in doing this may not be to emphasize or conceal their identity, rather it may be to emphasize or conceal a specific character trait that is associated with that identity. If someone from the South wanted to emphasize their hospitality (a trait associated with southerners), they can do so by up-playing their southern-ness with language. All social identities, whether related to heritage, gender, race, or sexuality, come along with a complex web of associated meanings that people can utilize in constructing their identity.

As a linguistics major, I am interested in the scientific study of the ways that language functions in the world. Through coursework and time as a research assistant in the linguistics department at the University of New Hampshire (UNH), I read about and worked on projects relating to social identity and language variation in New England. In the summer of 2020, I decided to conduct an independent research project with a Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) that developed into a senior honors thesis in fall of 2020. The objective of my research was a better understanding of the sociolinguistics of gay male speech in southern New Hampshire.

In this study, I explored how the social meanings of regional dialects interact with identities such as sexuality. My first goal was to analyze gay male speech for different variables, such as vowel pronunciation and pitch (how high or low someone’s voice is). My second goal was to observe the correlation between these variables, explore how gay male identity interacts with regional dialectology, and understand how this relationship may vary depending on the speaker’s situation and subject matter. As southern New Hampshire has undergone (and is continuing to undergo) a rapid dialect shift rooted in younger speakers’ desire to create a granite-stater identity distinct from neighboring areas, the region provided an excellent area to test the hypothesis that social identities such as sexuality and regional stereotypes are interrelated.

Constructing Identity with Language

Some may dismiss the notion of “gaydar,” or the idea that someone can accurately guess someone else’s sexuality from their body language, clothing, or the way they walk, as a myth, or maybe even inherently problematic. However, studies have shown that people can accurately guess someone else’s self-identified sexuality from a single read word (Munson et al., 2006). How does this happen? Although researchers have agreed that the way that someone pronounces the letter /s/ plays a large part in the perception of someone else’s gayness and the way that gay men construct their identities linguistically, regional accents seem to play a large part as well. Research has shown examples of gay men in California using more exaggerated versions of the current shift in California’s accent (e.g. “wreck” and “kettle” pronounced like “rack” and “cattle”) to express their gayness (Podesva, 2011). In a study of the gay male speech in Minnesota, the pronunciation of certain vowels associated with the regional dialect, such as the “a” in “bag” (being pronounced closer to the “e” in “beg”), appeared to play a part in what motivated participants to rate speakers as gay or straight (Munson et al., 2006).

Just like the relationship between a southern accent and hospitality, the relationship between regional dialects and sexuality are not necessarily direct. Regional identity and sexuality are both linked to ideas about masculinity, class, race, personality characteristics, and more in the popular consciousness, providing an indirect ideological link between these dialects and sexuality. Like the dialects of Minnesota and California, the dialect of English spoken in southern New Hampshire has several vowels that are undergoing generational changes and have social meanings that gay male speakers utilize to construct their linguistic identities. To contextualize the social meaning of regional dialects in southern New Hampshire, my project relied on a great deal of data from recent linguistic research in the area.

In the past couple of decades, the vowel pronunciation of southern New Hampshire’s youth population has shifted away from that of the Massachusetts dialect that dialectologists have traditionally grouped it with. This transition has been of great recent interest to researchers. At the same time, unique traditional vowels from the regional dialect in southern New Hampshire are receding in younger generations.

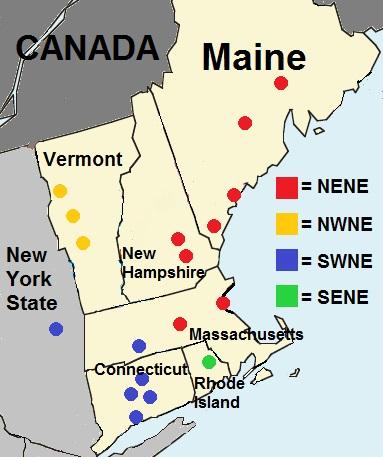

Map of the traditional groupings of New England dialects. NENE = Northeastern New England English (includes New Hampshire and eastern Massachusetts, traditionally), NWNE = Northwestern New England English, SWNE = Southwestern New England English, SENE = Southeastern New England English. (Map credit: Wikipedia Commons "New Eng;and English map.")

Different people in different places pronounce the vowels in the same words in different ways. Words can be categorized into vowel classes, which are groups of vowels that are pronounced the same, stylized in all upper-case letters. For example, the START class includes words that contain the same vowel as the “a” in “start”. Over time, the pronunciation of these vowels can change, and vowel classes can merge with one another. Although merged for many younger speakers today, the FATHER and BOTHER classes are not merged in the traditional New England dialect, with the vowel in FATHER words being pronounced closer to the “a” in “cat” than it is to the “o” in “bother”. START vowels in the traditional dialect and are pronounced similarly to FATHER vowels (close to the “a” in “cat”) and are notably “r”-less as well (“Pahk the cah in Hahvahd Yahd”). Also “r”-less in the traditional dialect are the vowels in NORTH and FORCE words. These vowels also do not rhyme traditionally, with FORCE words like “hoarse” being pronounced like “huss” and NORTH words like “horse” having the same vowel as “go”.

For young speakers in southern New Hampshire, however, the NORTH and FORCE vowels do rhyme. The FATHER and BOTHER classes have also merged and rhyme with one another. The vowel in the START class also rhymes with both FATHER and BOTHER and, notably, young granite staters do pronounce the “r”. On the other hand, some features of the traditional New Hampshire accent, such as the pronunciation of THOUGHT and LOT vowels, remain the same in the dialect of younger granite staters. While in some other parts of the country the THOUGHT vowel is raised (like in New York City “caw-fee”), THOUGHT and LOT are merged and therefore rhyme for both older and younger speakers in New Hampshire.

Stanford and his co-authors argue that these drastic and rapid changes are due to younger southern New Hampshire speakers’ negative associations with both southeastern Massachusetts and “older generations of ‘backwoods’ people in northern New England,” two demographic groups from which younger southern New Hampshire speakers want to distance themselves. While some features have remained consistent along generations, a significant amount of the features of southern New Hampshire’s dialect have changed in the past decades.

Some recent, thought-provoking developments in the field of sociolinguistics also informed my research. Variationist sociolinguistics, the most traditional sociolinguistic school of thought, draws its conclusions from large quantitative statistical analyses of language (typically phonetics) of people compared among rigid, census-like identity labels, such as “gay,” “straight,” “White,” “Black,” etc. In this approach, research inherently operates under the assumptions that the people in each identity “naturally” speak in certain ways. If an individual does not speak in this “natural” way in certain situations, this is due to paying extra conscious attention to speech or modifying speech to accommodate different audiences, depending on the researcher’s perspective (Meyerhoff, 2011). However, people do not go about their daily lives with such rigid identities. Identity is much more fluid than it is box-like, so a methodology that treats them as box-like is incapable of giving us a full picture of the relationship between language and identity.

Thus, researchers and theorists in recent decades have built upon the findings of variationist sociolinguistics with a newer methodological model of understanding identity-based language variation, including the integration of concepts like “stance.” Building upon our knowledge of how different groups of people tend to speak, the sociolinguistics of stance explores how these tendencies vary based on speakers’ personal ideologies about speech and identity. This method treats different styles of speaking (such as a gay style, a female style, or even a relaxed style) as signifiers of a speaker’s stance towards the subject matter, the audience, and their own identities. Stance-based sociolinguistics explains identity-based language variation as the indirect result of one’s stance towards a personal identity, rather than as a direct result of the identity of itself. For many people, especially those whose social identities inherently defy these stereotypically linked meanings, stance allows them to navigate their complex identities linguistically. However, this approach is not easily quantifiable, as it requires a large amount of ethnographic information and subjective analysis by the researcher. The body of stance-based sociolinguistic research reflects many strategies to quantify stance and reduce subjectivity, which I utilized to develop my research methods.

Methodology

To obtain speech data, I conducted and recorded IRB-approved reading tasks and interviews with two twenty-two-year-old gay men from Rockingham County in southeast New Hampshire (NH), both of whom are friends of mine. One is Black and the other is White. The interview questions pertained to opinions about the gay community, opinions about southern NH, opinions on stereotypical gay language use, and more emotional topics such as coming out. These questions were designed to elicit the widest possible range of stance situations and to gather as much pertinent ethnographic information as possible. Digressions were allowed and encouraged to simulate a naturally flowing conversation and increase participant comfort. The interviews each lasted about an hour. Due to COVID-19 regulations and concerns, these interviews were conducted over Zoom, and the participants were provided with high-quality audio recording equipment so that any measurements of their speech would be as accurate as possible.

The reading tasks were modeled after those used in Stanford et al. (2012), a major study on New England English in southern New Hampshire. The reading task section lasted about ten minutes for each participant, and consisted of two multi-paragraph passages, a list of single words, and a list of sentences. All of these passages, words, and sentences were designed to contain many instances of the vowels and consonants of interest, as well as maintain methodological continuity with previous studies done in this region. The reading tasks were conducted in the same meeting sessions as the interviews, and were recorded in the same manner.

My study relied on a number of measurements that have been found to correlate with a “gay-sounding” /s/. The two most consistent measurements are higher center of gravity (mean frequency) and more negative spectral skew (higher concentration of energy above the center of gravity than below) (Zimman, 2013). These measurements describe properties of sound waves that correlate to how front or back the /s/ is—literally, how far forward or backward in the mouth the /s/ is produced, which is recognized culturally as the “gay lisp.”

For the bulk of the project, I performed both qualitative and quantitative analyses of the recordings. I first transcribed the interviews, and then marked the vowels and the instances of /s/ that I wanted to study. This enabled me to then pull the relevant acoustic data using a script in Praat, a software capable of measuring certain aspects of sounds in question. For the quantitative analysis, I compared the presence of variables that traditionally signify a gay male stance with the presence of salient New Hampshire and Massachusetts variables, such as the vowels in NORTH, FORCE, LOT, THOUGHT, and START, the positions of which correlate with different demographics and regions within New England (Stanford et al., 2012). I primarily focused my research on these vowels and on various measurable properties of /s/, the most widely studied variable in gay male speech.

I applied a stance-based perspective, as described above, for the qualitative analysis. I used both ethnographic and contextual information to analyze the use or avoidance of specific gay male or regional linguistic norms in different situations throughout the interview. The stance distinctions I studied were whether the participant was speaking about being gay or experiences related to gayness, whether the participant was speaking about experiences in or opinions about urban or rural areas, whether the participant was “stereotyping” (speaking about broad generalizations of groups of people), and whether the speech data came from the interview or reading sections.

Results

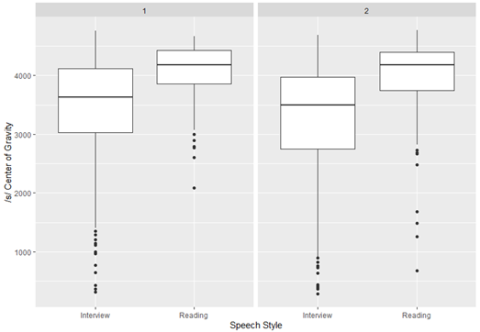

There were two main statistically significant results found in the study: one related to the production of /s/, and the other related to vowels from regional dialects. I discovered that there was a statistically significant difference in the /s/ center of gravity between the reading task and the interview task, and between when the participants were talking about being gay and when they were not. Unsurprisingly, the higher centers of gravity (correlated with sounding gay) were found when the subject was talking about being gay than when they were not.

Figure 1: Box plot comparing the center of gravity of /s/ between the interview and reading task for both Subject 1 (on the left), and Subject 2 (on the right). Note that, for both participants, the center of gravity of /s/ was significantly higher in the reading task than it was in the interview

Although one may expect the interview speech to be more “authentic” than the reading task speech, both participants’ centers of gravity ended up being higher and therefore “gayer-sounding” in the reading tasks than those in the interview tasks. However, the driving factor for the use of a “gay-sounding” /s/ in this situation doesn’t seem to be to emphasize gayness directly, but to emphasize certain personality traits, such as carefulness, that are associated with gay men. Previous studies have shown that ideological links exist between gayness and carefulness, such as the hyper-articulation of /t/ at the ends of words in the speech of many gay men (Eckert, 2008). This finding very explicitly demonstrates the need to re-think identity as more of a deeply interrelated web of meaning than simple, discrete, categorical labels.

The second major finding of the study was that both participants produced significantly unmerged LOT and THOUGHT vowels. Although these words (and all words that rhyme with them) are usually merged in both New Hampshire and Massachusetts, the two participants pronounced the THOUGHT vowel differently than the LOT vowel so that the THOUGHT vowel was “raised” (e.g. New York City pronunciation of “coffee” as “caw-fee”). This is of particular interest, because both participants indicated that, because of their sexual and/or racial minority statuses, they did not feel entirely comfortable in either New Hampshire or Boston. However, they did both explicitly refer to New York City as a safe and comfortable metropolis for gay men. As it is not possible for a region to “unmerge” sounds once they are merged, it is likely that these participants are mimicking a part of the classic New York City accent that is recognizable even as far as New Hampshire. It appears that these participants’ personal ideologies supersede regional dialect systems and common ideologies about them. Although the unmerged THOUGHT and LOT is typically thought of as a marker of being a New Yorker, this data shows that it (and many other linguistic variables that are associated with certain groups of people) can also be used to be a marker of a more abstract ideological alignment with New York.

Final Thoughts

In all, through the stance-based methodology, I arrived at explanations of language choice that simple averages and categorical labels wouldn’t be able to provide. The findings of significantly “gayer sounding” reading tasks and unmerged LOT and THOUGHT vowels demonstrate that people can creatively utilize stereotypes and ideas about categorical identity to express their own personal beliefs about these identities. The takeaway is not that social categories or the discussion of them is meaningless, but simply that they are socially constructed, mutable, and complex.

On a personal level, this project provided a great opportunity to be able to explore the contentious issue of social identity using methodology I am passionate about. While COVID provided some challenges to conducting the project up front, I ended up finding ways to work around it, and greatly enjoyed the project overall. I plan to continue my studies in the field of sociolinguistics in the near future, and hope to become a professor at a research-intensive university so that I can continue to expand on this knowledge and share it with others who are interested in these topics.

First and foremost, I would like to thank Dr. Rachel Steindel Burdin for the mentorship not only on this project, but also for her mentorship as her student, research assistant, and advisee. None of this would have been possible without her guidance. Secondly, I would also like to thank the staff at the Hamel Center for Undergraduate Research and Mr. Dana Hamel, who made the funding of this project possible. Last, but not least, I would like to take this opportunity thank my friends (including those who generously participated in this project) and especially my family for their endless support.

References

Eckert, P. (2008). Variation and the indexical field. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 12(4), 453–476. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2008.00374.x.

Meyerhoff, M. (2011). Introducing sociolinguistics. London: Routledge.

Munson, B., McDonald, E. C., Deboe, N. L., and White, A. R. (2006). The acoustic and perceptual bases of judgements of women and men’s sexual orientation from read speech. Journal of Phonetics 34: 202–40.

Podesva, R. (2011). The California vowel shift and gay identity. American Speech, 86(1), 32-51. https://doi.org/10.1215/00031283-1277501.

Stanford, J. N., Leddy-Cecere, T. A., & Baclawski, K. P. (2012). Farewell to the founders: major dialect changes along the east-west New England border. American Speech, 87(2), 126-169. https://doi.org/10.1215/00031283-1668190.

Zimman, L. (2013). Hegemonic masculinity and the variability of gay-sounding speech: The perceived sexuality of transgender men. Journal of Language and Sexuality, 2(1), 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1075/jls.2.1.01zim.

Author and Mentor Bios

Hayden Stinson is a University Honors student majoring in linguistics and Spanish, with a minor in philosophy. He came to the University of New Hampshire (UNH) from Chester, New Hampshire. A Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) award supported Hayden’s research on gay male speech patterns in southern New Hampshire, and he continued with his research work to complete his senior thesis. Like other researchers during the COVID-19 pandemic, Hayden encountered challenges to conducting interviews and other work that was part of his research plan: how to get audio recording equipment to his study participants by following pandemic safety protocols, for example. However, he persevered through the challenges, and though the steps of the research process took longer than expected, the result was a success: “It felt amazing when it all came together and I started to come to conclusions.” Hayden is enthusiastic about sharing his research and its implications about identity in our everyday lives and hopes Inquiry readers find the topic as interesting as he does. After graduating in spring 2021 with a bachelor’s degree, Hayden will work toward becoming a professor of linguistics and plans to continue conducting research. He views his undergraduate project at UNH as just the first step in a career of research and teaching.

Rachel Steindel Burdin is an assistant professor of linguistics in the English department and the women’s and gender studies department at the University of New Hampshire (UNH), where she began working in 2016. Her areas of specialization are sociophonetics, linguistic variation, and intonation. Hayden had been Dr. Burdin’s advisee since he started at UNH, and he went on to work as a research assistant for her. When he received a Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) for the summer of 2020, they successfully negotiated the logistical challenges of starting up his independent research near the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, with its important safety protocols. Dr. Burdin notes that learning to work with the COVID-19 challenges in the spring of 2020 helped her set up for mentoring other students during the subsequent fall 2020 and spring 2021 semesters. Hayden’s research project on gay male speech was a natural spin-off from Dr. Burdin’s ongoing project on language change and variation in New Hampshire. She explains that the field of linguistics is relatively obscure, though linguists strive to answer questions we all find fascinating: “How do children learn language? Why do different people have different accents? Why is it so hard to get a computer to understand what I'm asking?” Dr. Burdin describes writing for Inquiry as good experience for Hayden to practice communicating what linguistics is and to let the public know there are researchers exploring these intriguing questions.

Copyright 2021, Hayden Stinson