Media, Gender, and National Identity in Almaty, Kazakhstan

The visuals we encounter every day present us with messages that convey cultural norms and values; billboards, magazines, books, television, and social media provide information about culture and gender, which are mutually informative. In the summer of 2019, I traveled to the city of Almaty, the cultural center of Kazakhstan, to conduct exploratory research on gender as it is transmitted in the mediascape. Mediascape refers to “a landscape of images that produce and disseminate information (newspapers, magazines, television stations, film production studios, etc.) . . . and to the images of the world created by these media” (Appadurai 1990, 298). My research was intended to develop a deeper understanding of gender representations in Almaty through analysis of the local mediascape, specifically magazines and billboards.

The author at Lake Kaindy, a few hours outside Almaty, Kazakhstan. Photo credit: Rory O’Neil.

Kazakhstan may seem like a random country in which to conduct such research, and in a way, it was. As a political science and international affairs major studying Russian, I hoped to study abroad in Russia. Because of State Department travel advisories, I also looked into traveling to other countries where Russian is spoken. Kazakhstan, an independent country (1991), is a former Soviet Socialist Republic where Russian is still the primary language. I became intrigued by Kazakhstan’s pre-Soviet nomadic and Soviet history and how and why Russia continues to influence its culture and politics.

I decided to pursue independent research in Kazakhstan through the Hamel Center Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) Abroad program, with University of New Hampshire (UNH) professor Svetlana Peshkova as my research mentor. Dr. Peshkova, an anthropologist whose research is about religion and gender in former-Soviet central Asia, helped me formulate a research focus on gender dynamics in Kazakhstan, which has recently claimed gender equality as one of its primary policy foci (Astana Times 2019). Dr. Peshkova helped connect me with Dr. Nurseit Niyazbekov, a professor of international relations at KIMEP University in Almaty, Kazakhstan, who served as my foreign mentor.

During the fall of 2018, the State Department travel advisory for Russia was reduced, allowing me to study abroad in St. Petersburg, Russia, for the spring semester of 2019. While I was there, I worked with Dr. Peshkova via Skype and email to prepare for my independent research in Kazakhstan that summer. After finishing my semester in Russia, I spent two weeks traveling in central Europe before embarking for Kazakhstan (see map, Figure 1).

I have never experienced such anxiety as I did in my first few days in Almaty. I wasn’t sure if I was prepared to spend another two months away from home. I missed my family, I missed feeling at ease, I missed feeling like I belonged. Though I had experienced these feelings while studying in Russia, I had had the safety net of my study abroad program and my American friends in St. Petersburg. But in Almaty, these supports were gone. Luckily, my sister was able to come to Almaty and spend the summer with me, which helped. But I also wasn’t sure if I was prepared to conduct independent research. Though I met with my foreign mentor, Dr. Niyazbekov, upon arriving in Almaty, I still felt unsure of myself, as I had no prior research experience. I quickly learned to take things one day at a time, to embrace my outsider identity and use it to make friends, and to make peace with uncertainty in my research and instead use it to motivate my work.

Gender in Kazakhstan

Figure 1: A political map depicting the countries of the Caucasus and Central Asian region, with Kazakhstan shown in yellow. Source: https://legacy.lib.utexas.edu/maps/kazakhstan.html.

In the past century, Kazakhstan’s gender roles have gone through significant changes. Before imperial Russian and later Soviet influences entered Kazakh life, their nomadic society lacked a unified national identity, and gender roles were based on a gendered division of labor, with men often filling the roles of defenders and herders and women focusing on caring for home and children and extended family members. The Sovietization of Kazakh society both pre– and post–World War II resulted in the settling of nomadic Kazakh peoples, the Russification of their culture, and the formation of new gender roles based on Soviet gender-equality policies. Education and literacy rose among both boys and girls, and women were increasingly encouraged to enter the workforce as well as maintain their domestic roles. Meanwhile, men especially were groomed and chosen for positions of power within the Communist Party and Soviet government.

Today in Kazakhstan, these Soviet gender-role legacies are being challenged by the new trend of re-traditionalization of Kazakh culture. The re-traditionalizing is reviving conservative, nomadic conceptions of gender that confine women to domestic roles and men to breadwinner roles, in an attempt to foster a sense of unified Kazakh national identity (Anagnost 1997; Werner 2009). This current trend in Kazakh gender norms is in stark contrast with the Kazakh government’s statements that gender equality is one of its main goals, especially in relation to the country’s overarching aspiration to enter the ranks of the top thirty most developed countries by 2050 (Astana Times 2019).

Gender in the Mediascape

Anthropologist Arjun Appadurai (1990) argues that we absorb information about our culture and identity through five dimensions: ethnoscapes, technoscapes, finanscapes, ideoscapes, and mediascapes. Mediascapes especially convey sociocultural information to viewers on a daily basis. Peshkova (forthcoming) argues that gender is an analytical category referring to a sociocultural construction used to differentiate among individuals in society by dividing them into culturally acceptable categories; gender is one means of maintaining social order. All mediascapes that exist around the world are littered with stereotyped images of gender, which “sustain and reinforce socially constructed views of the genders” (Wood 1994, 236).

Research on how gender is portrayed in the mediascape in Kazakhstan is important because it demonstrates the role that gender plays in sociopolitical systems. Further, Kazakhstan is the leading power in central Asia because of its large geographical size and its booming economy, which is based on its large oil reserves. A geopolitical emergence of a “New Cold War” in the 2000s, characterized by tensions between the West, China, and Russia, and the dominant role Kazakhstan plays in the central Asian region, make this country important to US foreign policy interests. To understand the Kazakh political system, it is critical to understand the role of gender in it. As Kazakhstan’s former capital and current “cultural” capital, the city of Almaty, where I conducted research, is a cosmopolitan center that can set trends on gender representation in the entire country. By analyzing gender as it is portrayed in Almaty, I hoped to learn about the gender-role ideals that are conveyed to urban Kazakh citizens through the media.

Observing Gender and Mediascape in Almaty

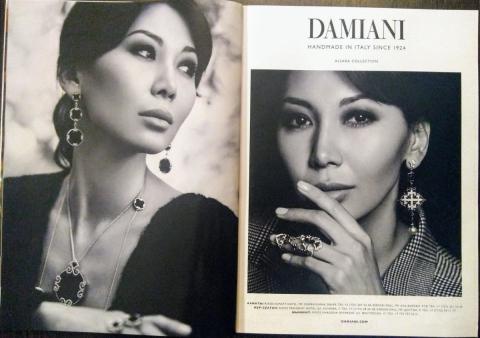

Figure 2: An example of a magazine advertisement. It depicts a Kazakh model wearing jewelry from an Italian company with some text in English and some in Russian.

I used social science methodologies in my research, including content analysis (the analysis of images) and discourse analysis (the analysis of texts, speeches, conversations, and so on). For such methodologies, it was important that I immerse myself in Almaty’s culture to supplement my analysis with real-life observations of how people in Kazakhstan portray and perform their gender.

I started by purchasing magazines at a local grocery store, choosing three that targeted female audiences and three that targeted male audiences. For the female-target magazines, I analyzed Cosmopolitan Kazakhstan, Harper’s Bazaar Russia, and Caravan, a local Kazakh magazine. For male-target magazines, I looked at Men’s Health Russia, Forbes Kazakhstan, and GQ Russia. I chose these magazines because they were among the most popular in Kazakhstan and were easily accessible.

Over the next two months, I spent much of my time in coffee shops around Almaty. Spending time in cafés is a great way to learn about urban Kazakhs, as coffee shops play a big role in Almaty’s culture. The cafés in Almaty were not unlike those found in US cities, but they were often

Figure 3: An example of a billboard in Almaty. Such billboards could be found on nearly every block. This billboard depicts a businesswoman and text in both Kazakh and Russian.

fancier and more formal. Young Kazakh women were always very fashionable and dressed up, and people would more often go to coffee shops for social meetings than to work on their laptops like they often do in the US.

Nevertheless, usually with a latte in hand, I would sit in a café and analyze each advertisement and photo-based article in each magazine and record my analysis in a codebook I developed in Excel (see Figure 2). The codebook designated more than fourteen categories for which I analyzed each advertisement and article. These categories included the gender of the characters, their age, their setting, and their body type. I also analyzed each character for a level of objectification, which looks at the extent to which each character is presented as a human being or as an object whose physical appearance or sexuality is used to sell a product or idea. I ranked characters on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being no objectification and 5 being severe objectification. Finally, I looked at the traits and themes most often associated with each gender, such as strength, weakness, beauty, authority, passivity, and so on.

I used the same codebook to analyze billboard advertisements, which I took photos of while walking around downtown Almaty (see Figure 3). The billboards could advertise anything, but they had to feature a human character in some way. Billboards differ from magazines in that they target a much larger and broader audience, whereas the magazines generally target a specific gender and type of person. I analyzed a total of eighty-nine images from magazines and billboards.

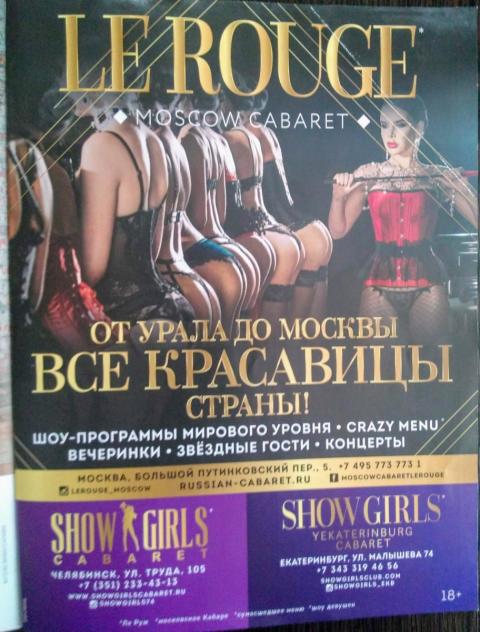

The use of a codebook allowed me to evaluate subjective traits more objectively and scientifically. For subjective traits such as objectification or thinness, I created a scale for each trait before beginning analysis, defining what each level along the scale would look like. In Figure 4, below, Level 1 objectification (as seen on the left) is the lowest and is defined by a human character who is used to sell a product in a highly relevant way that does not rely solely on their appearance. Level 5 objectification (as seen on the right) is the highest and is defined by human characters who are selling a product based solely on their appearance and body parts in a way that is explicitly sexualized.

Advertisement showing highest objectification.

Figure 4. Advertisement showing lowest objectification.

Following my analysis of the eighty-nine magazine and billboard images, I quantified the data I had recorded. I calculated the rate of occurrence for each trait in terms of percentages to uncover larger trends in how gender is portrayed in Almaty’s mediascape. Because statistical analysis is quantitative in nature, it can sometimes obscure important qualitative findings in research like mine. However, because I am performing statistical analysis on inherently qualitative data, it can actually help reveal larger patterns that may have otherwise been lost or overlooked in a purely qualitative analysis. It is important to note, however, that despite precautions, it is likely that my Western-based understanding of gender roles may have influenced my analysis of these sources.

It is also important to note that content and statistical analysis of media only inform us about gender roles but don’t determine how humans feel about and express their gender identity. That is to say that the data gathered on Kazakh gender roles through my research may either challenge or support how Kazakh people actually understand and perform their gender roles but does not definitively identify gender roles in Almaty.

It is also necessary to note that some of the magazines analyzed were Russian based rather than Kazakh based. This means that they may more closely reflect Russian gender roles than Kazakh gender roles. However, these sources are no less relevant to this research, as Kazakhstan, and Almaty in particular, has long been a center where many different cultural ideas converge to influence Kazakh society

Gender-Role Findings in Almaty, Kazakhstan

Based on my research sample, I found that male characters and female characters appeared at about the same rate in the Almaty mediascape. There was practically no presence of gender-nonconforming or gender-ambiguous characters in Kazakh billboards or magazines, with a total of only four characters, all of whom were children, who could be identified as gender nonconforming. This suggests that there are relatively strict expectations for how females and males should present their gender and there is not much acceptance in the Almaty mediascape for those who identify as gender nonconforming.

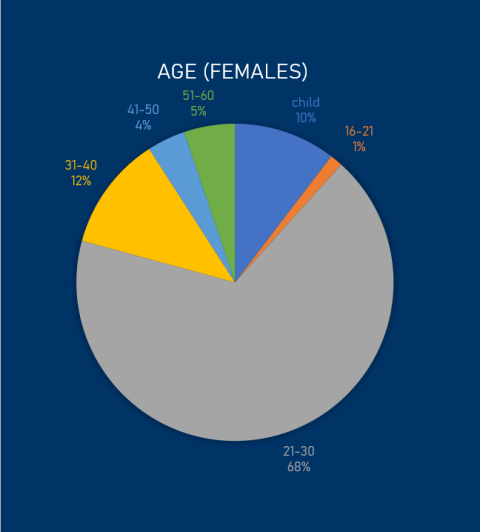

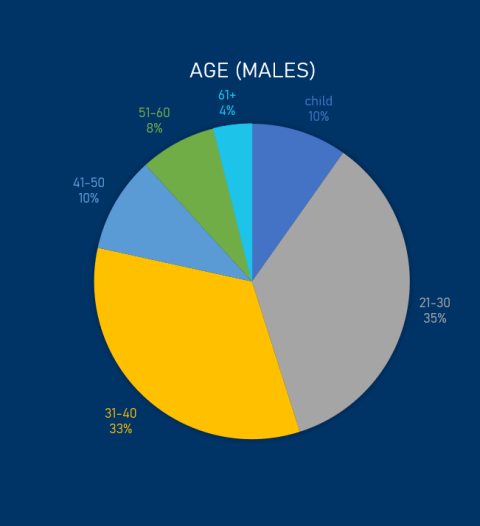

Female characters were often portrayed as young, appearing between the ages of twenty-one and thirty more than 60 percent of the time, whereas male characters were more likely to be portrayed as slightly older, between the ages of twenty-one and thirty only 35 percent of the time, and 33 percent of the time between the ages of thirty-one and forty. (See Figure 5.) This could suggest that Kazakh gender roles put a greater value on youth in women, which is often associated with beauty and fertility, and a greater value on maturity in men, which is often associated with professional success, power, and authority.

Figure 5: Charts depicting the age distribution of characters in Kazakh media based on gender. The chart on the top shows that over 2/3 of female characters were depicted as being between the ages of 21 and 30, whereas the chart on the bottom shows that only about 1/3 of male characters were depicted as being between the ages of 21 and 30.

There are also some interesting differences in the settings where female and male characters were placed. Although neither men nor women were very likely to be presented in a workplace setting, men were still twice as likely as women to be seen in a workplace setting. In addition, women were four times more likely than men to be presented in a home environment. These differences suggest that Kazakh gender roles associate urban, middle-to-upper-class men more closely with work and careers, and urban, middle-to-upper-class women with homemaking.

Female characters were more likely to be portrayed in objectified and/or sexualized ways than male characters, with 76 percent of all female characters receiving objectification scores of 3 or above (1 being little to no objectification, 5 being extreme objectification), whereas only 63 percent of male characters received objectification scores of 3 or above. Female characters were also the only ones to receive an objectification score of 5, whereas no male characters were ever presented as extremely objectified.

Analyzing the mediascape in Almaty offered insight into gender roles associated with authority. Less than 8 percent of female characters analyzed were portrayed in a position of authority, but male characters were shown in positions of authority almost 20 percent of the time. This may suggest that the gender roles in urban Almaty more closely associate power and authority with men.

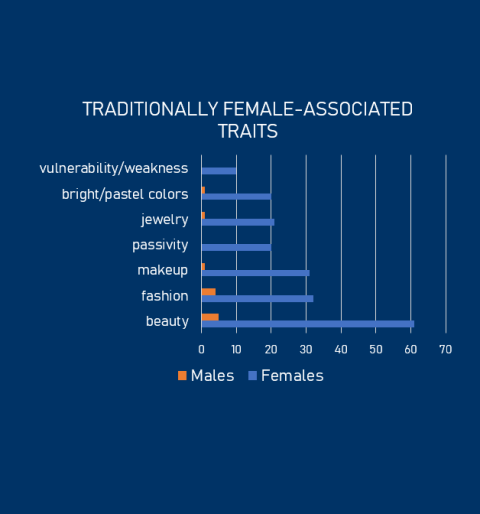

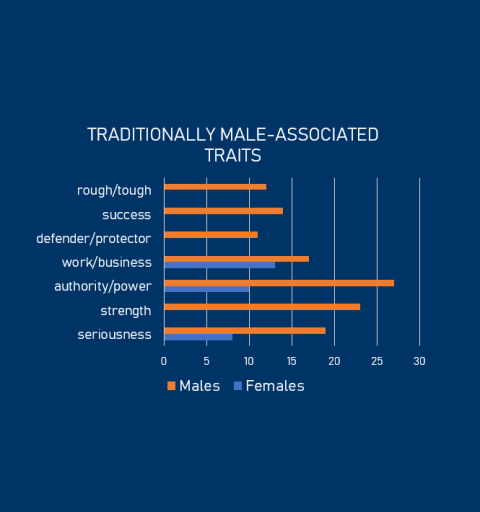

Interestingly, the occurrence of traditionally male traits being presented in female characters was not the same as the occurrence of traditionally female traits being presented in male characters (see Figure 6). Male characters were occasionally associated with beauty, but very rarely associated with any other traditionally female traits, such as passivity, pastel colors, fashion, or makeup. However, female characters were much more often portrayed as possessing male traits, especially those of action and adventure, work and business, power and authority, and lack of emotion. This suggests that it is more acceptable in Almaty’s gender roles for women to be like men than for men to be like women. Thus, it seems that traditionally male traits are more highly valued overall in Almaty’s society than traditionally female traits.

My research revealed that Kazakh gender roles in urban Almaty prescribe relatively strict guidelines for how women and men should present their gender. Females are represented as putting great value on their outward appearance and beauty, including thinness, fashion, makeup, and jewelry. Women are also portrayed as being passive homemakers, rather than decisive and authoritative businesswomen.

Meanwhile, men are presented with a greater focus on their personality and achievements than on their outward appearance. Men can be either thin or muscular but are not encouraged to pay much attention to their appearance otherwise. Instead, the media portrays men as being intelligent and successful breadwinners who hold positions of authority and power, both within their career and their household. These gender roles are critical to Kazakhstan’s post-Soviet nationalism and the development of Kazakhstan’s national identity. My research findings support current theories that today, in an attempt to forge a strong Kazakh national identity to support their newfound independence, the Kazakh State has embraced a “(re)narrativization of the past” (Anagnost 1997; Werner 2009) that idealizes conservative, nomadic, gender roles (Werner 2009).

Figure 6: Charts depicting the traits most often associated with female and male characters in Kazakh media. The most common female traits were related to external appearance, such as beauty, while the most common male traits were related to more intrinsic characteristics, such as strength. Notably, it was much more common for females to be depicted with commonly male traits than for males to be depicted with commonly female traits.

A return to such conservative, limiting gender roles promotes a gendered division in society in which men are seen as the rightful leaders of the public and political sphere while women are increasingly relegated to the private, domestic sphere. This trend of gender-role re-traditionalization creates a stark disconnect from the Kazakh government’s stated goal of gender equality. Economic motivations have led Kazakhstan to seek greater acceptance from the Western world by claiming to champion gender equality, but the development of a distinct national identity is also a central government concern. It appears that the Kazakh government has, at least for now, prioritized its national identity building over its desire for further Western economic integration.

Conclusion

This research was successful in helping me develop a deeper understanding of Kazakh gender roles as they are portrayed in the urban mediascape, which is the first step to developing greater insight into Kazakhstan’s political culture and system. Though I would need to conduct further research to examine how Kazakh people actually understand and perform their gender and how that influences their political views, my current research provides the foundation for such explorations.

On a personal level, this research experience was transformative and enlightening. Studying abroad in Russia marked my first time traveling outside the US, and because I was not able to go home between Russia and my research in Kazakhstan, I ended up living abroad for six months. Both my time in Russia and Kazakhstan were incredible experiences, but they were also stressful at times. I learned how to be comfortable with being uncomfortable—with feeling like I didn’t quite fit in. My research in Kazakhstan was the first time that I faced the challenge of forging a completely new path for myself, of building something from the ground up, of creating a life for myself in a new place. I learned to be more outgoing, more independent, more courageous, and more confident.

Researching and traveling abroad also changed my worldview. I learned how much privilege came from my American passport but also my native language. Everywhere I went, people spoke English, were learning English, or wanted to learn English because they saw it as a key to a better life. Thus, my research experience not only helped me grow academically and professionally as a researcher but also helped me become a better global citizen by teaching me about myself and my privilege in an international context.

This research would not have been possible without the support of many incredible people. First, I would like to thank Mr. Dana Hamel, Mr. Frank R. and Mrs. Patricia S. Noonan, and Mr. John Greene for their generous financial support through the Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship Abroad program. Second, a huge thank-you to my UNH mentor, Dr. Svetlana Peshkova, whose steadfast guidance and encouragement helped me stay focused and confident in my research. Finally, I would like to thank my foreign mentor, Dr. Nurseit Niyazbekov, without whom this project would never have gotten off the ground.

References

Anagnost, A. 1997. National past-times: narrative, representation, and power. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Appadurai, Arjun. 1990. “Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy.” Theory, Culture, & Society 7:295–310. DOI: 10.1177/026327690007002017

Astana Times. 2019. “Kazakhstan Proud of Gender Equality Efforts, Continues to Seek More Equitable Society.” March 12. https://astanatimes.com/2019/03/kazakhstan-proud-of-gender-equality-effo....

Peshkova, Svetlana. Forthcoming. Gender Structure. Central Asia in Context. Pittsburgh, PA: Pittsburgh University Press.

Werner, Cynthia. “Bride Abduction in Post-Soviet Central Asia: Marking a Shift towards Patriarchy through Local Discourses of Shame and Tradition.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 15, no. 2 (2009): 314–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9655.2009.01555.x.

Wood, Julia T. 1994. “Gendered Media: The Influence of Media on Views of Gender.” Gendered Lives: Communication, Gender, and Culture. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing.

Image Sources

“Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection.” Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, University of Texas Libraries, https://legacy.lib.utexas.edu/maps/kazakhstan.html.

Author and Mentor Bios

Darby O’Neil was born and raised in Nashua, New Hampshire. She is a senior at the University of New Hampshire (UNH), dual majoring in political science and international affairs, as well as minoring in Russian. Throughout her time at UNH, Darby has been involved in the University Honors Program, Hamel Scholars Program, Dobro Slovo (Russian Honor Society), Pi Sigma Alpha Political Science Honor Society, and Phi Beta Kappa Honor Society. Darby had been interested in conducting research in Kazakhstan since her sophomore year, and the specific idea to study gender in the media came from her UNH mentor, Dr. Svetlana Peshkova. Darby was able to travel to Almaty, Kazakhstan, to conduct research after being awarded a Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship from the Hamel Center for Undergraduate Research. The transition was tough at times, especially since she had just spent three months studying abroad in Russia, but she found comfort and community in Almaty through group hiking trips and other social activities. Darby’s career path and goals may include public service work in Washington, DC, or somewhere abroad, as well as attending law school later in life. Regardless of where her path takes her, Darby’s research in Kazakhstan has instilled in her a newfound sense of adaptability, independence, and confidence.

Svetlana Peshkova has been at the University of New Hampshire (UNH) since 2009. She is an associate professor of anthropology who teaches ethnography, gender, Islam, feminism, and decolonialism. The courses she offers include Peoples and Cultures of MENA, Anthropology of Islam, Indigenous New England, and Ethnographic Methods. Dr. Peshkova’s main research area is the former-Soviet Central Asia, which made her involvement with Darby’s project a perfect match. Having mentored several undergraduate and graduate researchers at and outside UNH, Dr. Peshkova was well prepared for the process. One of the most difficult parts of the project, she said, was managing long-distance supervision of Darby’s project in Almaty, Kazakhstan. Nonetheless, she helped Darby conduct effective research, which supported their shared hypothesis about the importance of images in articulating gender roles in any society by informing and reflecting relationships among individuals. According to Dr. Peshkova, Darby’s research exemplified the relative importance of images in regard to the local gender dynamics in Almaty, Kazakhstan.

Nurseit Niyazbekov is an assistant professor at KIMEP University in Almaty, Kazakhstan. He specializes in research on democratization, social capital, and social movements, and he provided guidance to Darby while she was in Kazakhstan. Dr. Niyazbekov had mentored foreign postgraduate students in the past, but this was his first time working with a foreign undergraduate student. As Darby’s mentor for this research project, Dr. Niyazbekov assisted her with visa, travel, and living arrangements and provided her with research methodology advice.

Copyright 2020, Darby O’Neil