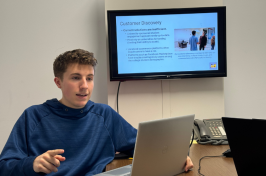

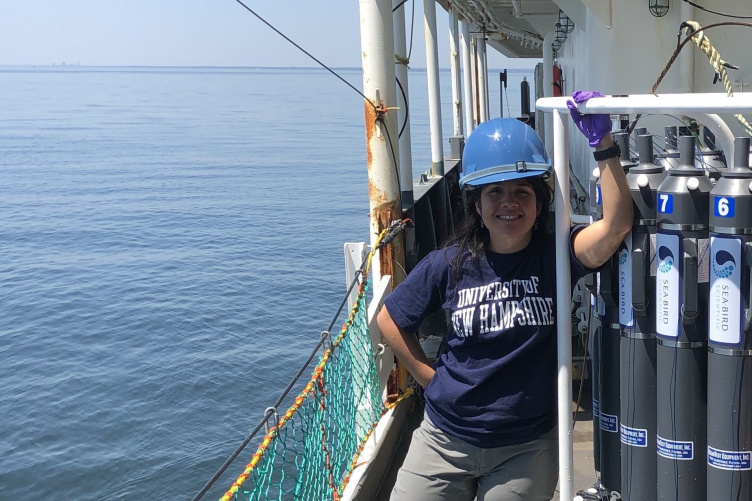

Doctoral student Melissa Meléndez-Oyola. Photo by Shawn Shellito.

Before finishing graduate school, UNH doctoral student Melissa Meléndez-Oyola will have served on Puerto Rico’s Climate Change Council, contributed to the fourth annual National Climate Assessment, advised and mentored students from her native Puerto Rico to increase minority participation in STEM fields and led Hurricane Maria recovery initiatives.

Now, a prestigious Ford Foundation Dissertation Fellowship award ensures that not even high-profile distractions like these will prevent her from turning in that dissertation and graduating.

Meléndez, who studies ocean acidification with Joe Salisbury, research associate professor in UNH’s Ocean Process Analysis Laboratory, says the one-year $25,000 stipend will “help me concentrate on doing my own work for the last year of my Ph.D.”

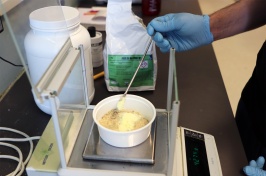

For her dissertation, Meléndez is working to understand ocean acidification — which occurs as oceans absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and their pH decreases, making seawater more acidic — using new modeling techniques and ocean observations. She’s using three of the many ocean-observing buoys worldwide: One on a coral reef in Puerto Rico, one in Florida, also on a coral reef, and one closer to her academic home in the Gulf of Maine. She’s developed a model to help estimate the health of the ecosystem by tracking how calcium carbonate — the building blocks of coral reefs — is dissolving.

“This project is essential because the current trend and projections on ocean acidification are well-defined in open ocean waters but we know less about how and when ocean acidification will affect coastal ecosystems such as coral reefs.”

Specifically, Meléndez wants to understand how coastal processes might be confounding the ocean acidification signal.

“This project is essential because the current trend and projections on ocean acidification are well-defined in open ocean waters but we know less about how and when ocean acidification will affect coastal ecosystems such as coral reefs,” she says. “In the tropics as well as here in the Gulf of Maine, there are a lot of freshwater inputs. How are these local effects masking this global phenomenon of ocean acidification?”

Her work could lead to a sort of early warning system for coral reefs that are in danger of dissolving, taking with them tourism and fisheries dollars as well as protection against coastal erosion.

Meléndez is grateful to be among the just 5 percent of fellowship applicants accepted by the Ford Foundation.

“The prestigious Ford Foundation Dissertation Fellowship represents the opportunity to strengthen my academic objectives and goals,” she says. “And as a minority in New Hampshire striving to foster passion and growth for others within my field, this fellowship is an opportunity to connect and learn from others striving to realize similar goals.

Now exploring postdoctoral positions, Meléndez calls her time at UNH fulfilling — “Joe Salisbury is very well-known in the ocean acidification world and has help me become a scientific leader” — but hears the tropics calling. “I’ve liked it here, but it’s a little cold,” she says.

-

Written By:

Beth Potier | UNH Marketing | beth.potier@unh.edu | 2-1566