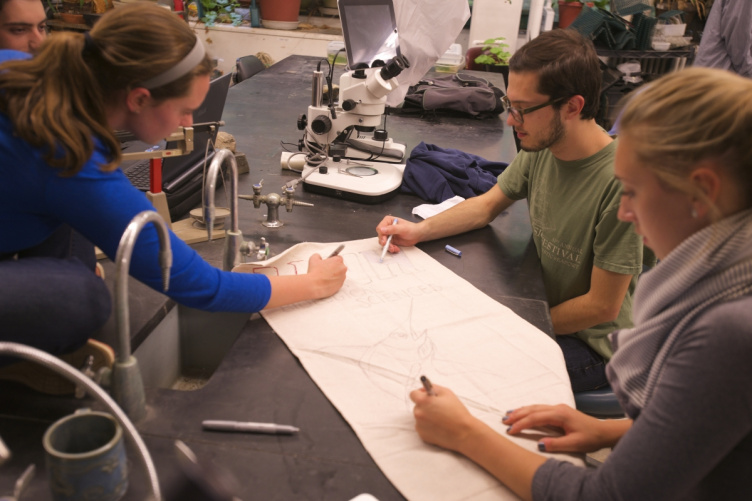

You might be surprised to find undergrads in a science class drawing and coloring, but that’s exactly what they were up to in a recent introduction to marine biology lab in the Spaulding Life Sciences Center at UNH. Sprawled out among microscopes and with markers in hand, students in groups of four spent the first 30 minutes decorating panels of cotton canvas.

Scientific anarchy? No, says Amanda Sobel '15G, the UNH graduate student leading the lab. “This is hands-on science.”

The panels will be used as sails on two vessels the students are building to help ocean scientists understand more about surface currents in the Gulf of Maine. Wind-generated currents that generally occur within the top few hundred feet of the ocean, surface currents impact shipping traffic, the weather and larval distribution of sea animals, among other things. Knowing more about their dynamics could help with storm track forecasting, oil spill mitigation and search and rescue operations, for example.

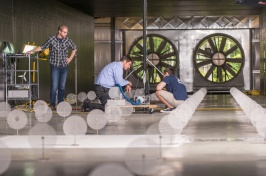

The vessels the students are building—called “drifters”—are simply constructed aluminum and wood units that will bob along the current, relaying their position periodically via satellite to scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Northeast Regional Association of Coastal and Ocean Observing Systems (NERACOOS). These scientists will add the information to a database housing all kinds of oceanic data that is made available to fishermen, recreational boaters, the Coast Guard and other scientists who study the ocean, climate change and atmospheric science.

The vessels the students are building—called “drifters”—are simply constructed aluminum and wood units that will bob along the current, relaying their position periodically via satellite to scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Northeast Regional Association of Coastal and Ocean Observing Systems (NERACOOS). These scientists will add the information to a database housing all kinds of oceanic data that is made available to fishermen, recreational boaters, the Coast Guard and other scientists who study the ocean, climate change and atmospheric science.

The students are building the “Irina” model, one of three drifter prototypes out there today. They’ll attach the sails to aluminum spars and lash on buoys so the drifters will float. Then they’ll screw square, wooden platforms to the tops and attach GPS transmitters to each.

The term “sails” is deceiving. The panels—indeed, most of the drifters—will be submerged, with only about a foot visible above the surface. “We need the sails in the water column in order to get the data about these particular currents,” says Sobel. The water will push the sails, helping give precise information about the currents’ movements.

The coloring of the sails wasn’t only for decoration, by the way. Each panel includes the name and phone number of the NOAA scientist who will recover the drifter should it wash ashore.

Drifters were first envisioned by NOAA scientists who needed an affordable way to track surface currents. Since deploying the first few a decade ago, the agency has collected data from thousands of drifters. Sobel says this exercise is a way for the students to use oceanographic tools and add information to a larger data set used by the scientific community. Their drifters will transmit data three times each day.

“It’s really interesting to watch the data come in,” says Sobel, who built her first drifter during a NOAA and NERACOOS conference in Woods Hole, Mass., earlier this year and launched it from NOAA’s R/V TIOGA into the Gulf of Maine in May. She says the experience was great fodder for the classroom. “This is hands-on marine biology. This is what real biologists are doing.”

Erik Chapman, the assistant professor of natural resources who teaches the course, says, “The drifter exercise illustrates to our students how physics drives biology in the marine system. You can’t understand marine biology without paying careful attention to ocean physics, particularly at the ocean surface.”

The drifter-building is just the beginning of a semester-long exploration into ocean data and its uses. After launching their drifters, each student will study a biological process of their choosing using data from drifters and other ocean‑observation instruments such as buoys and floats.

The students launched their drifters into the Gulf of Maine from the M/V Granite State on Sunday, October 12. You can monitor the drifters’ movements on the NERACOOS website.

Related:

There’s a Mount on the Bottom of the Sea

Over Their Heads in Algae at Shoals Marine Lab

UNH School of Marine and Ocean Engineering

-

Written By:

Tracey Bentley | Communications and Public Affairs