No one likes to think about their own mortality, especially the details of their funeral. But visiting artist Eric Adjetey Anang showed a group of UNH art and art history students that in his home country of Ghana, West Africa, a funeral is a celebration of life, not necessarily a somber occasion.

Anang is a custom coffin maker in the Ghanaian tradition. Families commission ‘fantasy’ coffins for their loved ones in various forms — an eagle, a lion, a fish, or even an airplane are among some of the designs created by Anang and his team of apprentices.

Anang spent last week working with woodworking and art students to build a coffin in the shape of a lobster — very appropriate to this New England setting. The finished coffin will eventually be donated to the Seacoast African American Cultural Center in Portsmouth.

Leah Woods, an associate professor of art and art history who teaches woodworking and furniture design, invited Anang to UNH. She first met him when she was traveling and studying in Ghana last year. He seemed an ideal visitor for her woodworking students, as the fantasy coffins are a perfect example of form meeting function.

“I knew I wanted him to come to UNH to show students a way of building, a way of making art, and at the same time honoring family, tradition and culture,” says Woods.

Anang’s weeklong visit included a lecture at the Paul Creative Arts Center on Monday, where he talked about his upbringing and his work.

The third generation to run the family business, Ghana Coffin, in Teshie, Ghana, he learned at the hand of his father and grandfather. The business started in the late 1940s, when Anang’s grandfather was asked to build a cocoa pod coffin for a local chief. It grew from there, and today Anang and his father work with eight apprentices.

Anang and his team make coffins for high-ranking community members as well as ‘regular folks’ — but he’s quick to point out that not all of his work focuses on the sadness of someone’s passing. Of the five or six pieces they work on each week, some are commissioned art pieces for museums or private collections. Last year, about 50 of his coffins ended up out of the country, Anang notes, as pieces of art rather than functional objects.

When it does come to the pieces that will serve as coffins, Anang has a reverence for the families who are mourning, as well as his craft.

“A family will come to the shop and of course they are very sad. I try to spend time with them, sharing with them, showing them photos of what we are working on,” he says. “And then they say ‘Ah, that’s the right guy we should place our order with,’ and so finally when they leave the shop, even though they’ve lost a dear one, they are smiling and happy.”

The fantasy coffin tradition is unique to the Ga people of southern Ghana. They seek to respect and honor their ancestors, believing they are more powerful than the living, so they are driven to appease them.

“To me [coffin making] is a very important profession. A lot of Ghanaians don’t have a good respect for it because you are working with death. But to me it is a great way of honoring someone who has played a vital role in life.”

UNH was the last stop on a five-month stay in the U.S., during which Anang taught at other colleges, picked up tools for his workshop in Ghana, and exchanged ideas and experiences with professors like Woods.

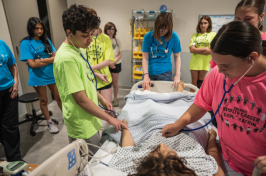

By the end of his week at UNH, woodworking students and Anang had completed the lobster coffin, and art students picked up brushes to help paint the structure. Sophomore Anna Tumber says that yes, in fact, this was the first time she had painted a giant lobster, and certainly the first time she had painted a lobster coffin.

“I’ve done murals, which I think are hard because they’re so big, but I love this,” she says. She attended Anang’s evening lecture, and had been stopping by each day to see the progress of the coffin.

Next to her with brush in hand was Laura Brocker, a second-year MFA student, who said Anang’s visit was interesting to her as an art student, but noted it was also a unique opportunity for the entire community.

“This is totally different, but it’s a good different … for UNH and even New England to see a cross-cultural practice and tradition,” she says. “Perhaps this raised some questions for people — what is this lobster coffin? Maybe people will think about or inquire to learn more about the practices and traditions of Ghana or even other countries because they’ve seen this.”

Want to see one in person?

If you missed the lobster coffin on the UNH campus last week but aren’t planning a trip to Ghana anytime soon, consider something closer like the National Museum of Funeral History, located in Houston, Texas. The museum houses a permanent collection of Ghanaian fantasy coffins, built by Kane Kwei, which features information on this unique tradition and on Kwei himself. Be ready to go with a bit of whimsy as you peruse this and other collections: the museum’s motto is “Any day above ground is a good one.”

Story and photos by Michelle Morrissey and Jeremy Gasowski of Communications and Public Affairs, and Olivia Marple ’15

-

Written By:

Michelle Morrissey ’97 | UNH Magazine | michelle.morrissey@unh.edu